Les Années folles. Photography, suits and shoes from the Shoe Icons collection

![Le mignon petit soulier [A cute little shoe].

Advertisement for Perugia shoes brand.

Artist: Jean Grangier.

A page from La Gezelle magazine.

France, 1924.](/upload/iblock/3cd/3cde691c6e6d61283fcc6d746104c636.jpg)

A page from La vie parisien magazine. France, 1926.

Unknown Author (by Acme). Shoes and leather show at Waldorf Astoria. New York, USA, 1936.

Unknown author (Culver Pictures Inc.). Sheer silk stockings so finely sensitized that a photograph can be printed upon the, is the latest whim of the smart young woman. Estelle Clark, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer player, conceived the idea of wearing the favourite boyfriend’s picture on her hose. She consulted one of the photographic experts at the studio and discovered that a chiffon stocking could be so highly sensitized that a photograph could be reproduced upon it. 1925—1928

Unknown Author (International Newsreel Photo) Peacock tongue. Something new in the shoe line. Just take one walk like showgoing. It is one of the exhibits at the boot and shoe show in London. It has all the colors of the peacock which it represents and threatens to become novelty. London, Great Britain, 1922.

Le mignon petit soulier [A cute little shoe]. Advertisement for Perugia shoes brand. Artist: Jean Grangier. A page from La Gezelle magazine. France, 1924.

Unknown author. Sally Rand appears in Paramount’s ‘The Dressmaker from Paris’. USA, 1925.

Charles Sheldon. Ad for Fox Shoes, 1915–1920.

Unknown author. Bebe Daniels in ‘Twoo weeks with pay’. USA, 1921.

Unknown author. 1920s.

Unknown author. Dancing couple. USA, 1930s

Unknown author. Merna Kennedy is doing the role of ‘Billie’ in the Universal’s ‘Broadway’. This bizarre negligee robe is of orange, red and yellow, quilted silk. USA, 1929.

Unknown author. USA, 1921–1923.

Moscow, 6.03.2019—5.06.2019

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Curators: Nazim and Elena Mustafayevy

For the press

Les années folles

Photographs, costumes and shoes from the Shoe Icons collection

Curators: Nazim and Elena Mustafaev

Architects-consultants: Kirill Ass and Nadezhda Korbut

Supported by Tele2

The 1920s and early 1930s have gone down in history as ‘mad’, ‘crazy’, ‘roaring’, ‘flourishing’. After recovering from the horrors of the First World War and economic crises of 1919 to 1920 the world sought to return to ‘normality’, to the joys of life not the suffering, to dances instead of tears, to diversity of colour in place of khaki. The First World War left deep scars in the psyche of a generation that had endured terrible slaughter, and as the first victims of weapons of mass destruction they learned to kill before they could live. This made them even more desperate to reap the benefits of peacetime and an era of economic prosperity. When describing the state of society in those years many intellectuals write of the ‘debauchery of the senses’, moral revolution and wasteful squandering of life that afflicted every class.

As the dominant style of these years Art Deco was, as Scott Fitzgerald famously remarked, shaped by ‘all the nervous energy stored up and expended in the War’. Originating in the early years of the 20th century, it was fully formed by the mid-1920s, holding sway at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in the design of clothing, fabrics, jewellery, interior design, household items and furniture.

Art Deco is regarded as the last major style that became widespread in almost every country and embraced every aspect of design. As its distinguishing characteristic, the emphasis on geometry, it was obliged to engender a new civilisation, at the heart of which, according to Spengler, lay ‘technology, the art of engineering, the mass spectacle and sport’. Circles, triangles, polyhedra, sharp zigzag lines, stylised sun rays, searchlight beams with lines of rhinestones, geometrically aligned foliate patterns, the bright colours of artificial diamonds — all these are recognisable characteristics of a style that can be seen in the dresses, shoes and heel decoration of the epoch.

The technocentricity of the new civilisation had a direct impact on the fashion industry. Standardisation and conveyer-belt production necessitated the advent of a single measuring scale. Mail order catalogues and the appearance of cheap new synthetic materials like viscose facilitated the transformation of fashion into a phenomenon of mass culture.

New technologies contributed not just to the mass distribution of goods, but also to the accelerated assimilation of fashion innovations. Department stores had started to combine the functions of shopping and entertainment centres, and by the 1920s they offered customers a top-to-toe fashion image, a ‘look’ as we say now, thus helping to overcome any fear of extravagant fashion innovations.

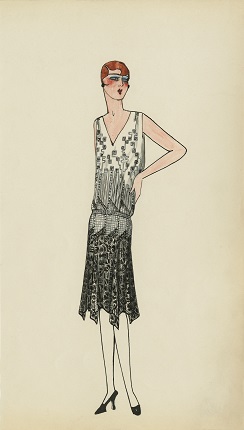

Fashion of the 1920s takes into account the requirements of the mass consumer: using the minimum amount of fabric, the silhouette arrives at the most stylistically simple cut, the tubular shape. This cut was available to the masses and dispensed with multiple fittings and time-consuming manufacturing processes.

At that period the design of clothing and footwear was hugely influenced by the new dance culture, which finally replaced Victorian traditions of etiquette with more relaxed social relations. In quick succession the Foxtrot, Rhythm-and-Blues, Charleston, Shimmy and Black Bottom reached Europe from America. Energetic movements required improvements in the design and reliability of footwear. From the mid-1920s the toe becomes more rounded, the heel lower and more stable. The central female fashion stereotype is now that of an infantile teenager with short-cropped hair. Bright colours, silver and gold leather, bugles, beading, rhinestones, metallic light-reflecting lamé fabric and long necklaces of beads or pearls lent an extra glamour to the twist and turns executed by fashionable young women on the dance floor.

Revolutionary changes in the social status of women and ability to demonstrate their sexuality more freely were also partly a consequence of the First World War: the mass mobilization of men meant that women had to fill vacant positions. The freedom for which generations of feminists and suffragettes had fought was unwittingly given them by the power of dire necessity. The emancipated woman of the 1920s actively developed new social roles — she provided for herself, no longer dependent on the man, she drove a car, indulged in pleasure and relinquished the conventions of older generations.

True to the spirit of the time the hem of women’s dresses grew gradually shorter, and by the mid-1920s it had risen to just below the knee. With the new dress length legs were always on show, and this contributed to increased interest in shoe design. Trends in the latest shoe models began to change more rapidly. There was a much greater variety of design and a wide-ranging selection of materials, colours and decorative refinements appeared. The fashion for Victorian boots that had been the stalwart of female footwear on all occasions for over half a century became a thing of the past. Now magazines and catalogues offered women ankle boots and closed shoes with laces, straps or elastic inserts. Pumps, previously regarded as suitable for indoor wear only, now made their debut on the street.

Buckles were still the simplest and most common decoration for footwear. They were sold separately and sewn or attached to pumps with a special clip. Also purchased separately were engraved, enamelled or rhinestone-encrusted metal plates to fit over buttons. Changeable details made it easy to transform a pair of ordinary pumps in monochrome material into a more elegant version for evening.

The heels inlaid with rhinestones that had vanished in wartime came back into fashion in the 1920s. They were carved from wood and covered with multi-coloured celluloid in imitation of ivory, mother-of-pearl or tortoiseshell. As well as rhinestone embellishments, some were painted with enamel.

‘Les années folles’, the ‘crazy years’, marked a time when the machine had not yet replaced the hand of the master and merely assisted him, as can be seen from the precision of workmanship and execution of decorative detail. This period gave us craftsmen in the high art of the shoe like André Perugia, Salvatore Ferragamo and Pietro Yantorny, and left us the legacy of firms such as I. Miller, Delman, F. Pinet, J. J. Slater, Bob Inc., Saks Fifth Avenue, Hellstern & Sons, Bally and the many others whose work is displayed in the exhibition.

One hundred years later it is no chance that we revisit Art Deco: this style still retains its relevance and nourishes the imagination of present-day designers, couturiers and architects.

Shoe Icons is one of the world’s largest collections of shoes and costumes, and also a publishing house created by Nazim and Elena Mustafaev specialising in books on the history of footwear.