Paradise Network

Recycle (Andrey Blokhin, Georgiy Kuznetsov). The Letter F. 2012. Cast polyurethane. Courtesy of Triumph Gallery

Recycle (Andrey Blokhin, Georgiy Kuznetsov). Gate. 2012. Corrugated tube, light box. Courtesy of Triumph Gallery

Recycle (Andrey Blokhin, Georgiy Kuznetsov). Gate. 2012. Corrugated tube, light box. Courtesy of Triumph Gallery

Recycle (Andrey Blokhin, Georgiy Kuznetsov). Lives of the Saints: Super Heroes. 2009. Window pane, plastic, foam board, marble paint, cocktail sticks. Courtesy of Triumph Gallery

Recycle (Andrey Blokhin, Georgiy Kuznetsov). Breathing. 2010. Cast polyurethane and stainless steel, electric motor. Collection of Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Recycle (Andrey Blokhin, Georgiy Kuznetsov). Cultural Layer. 2010. Cast polyurethane. Courtesy of Triumph Gallery

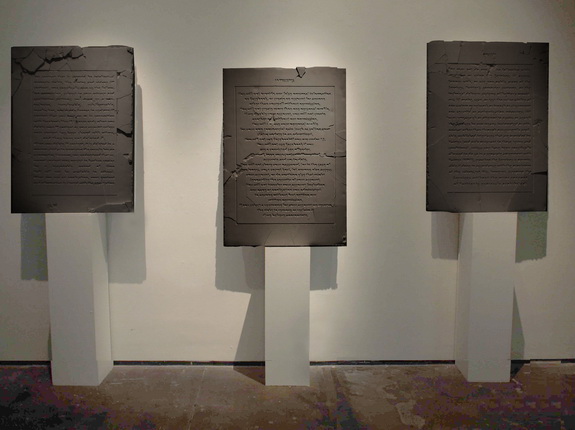

Recycle (Andrey Blokhin, Georgiy Kuznetsov). Tablets of the Covenant. 2012. Cast polyurethane, wood. Courtesy of Triumph Gallery

Moscow, 20.12.2012—20.01.2013

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Curator: Anna Zaitseva

Winners of the 2010 Kandinsky Prize in the category «Young Artist: Project of the Year,» Recycle Art Group (Andrey Blokhin and Georgy Kuznetsov) is already quite familiar to art lovers. The group’s logo is the international symbol for recycling. With help from the Recycle Group, car tires, waste containers, wires, drinking straws, plastic bags, and broken gadgets have received a second life in museums and galleries.

For the press

In its new project, Recycle continues to reflect on what our time will leave behind for future generations, what artifacts archaeologists will find after we are gone, and whether these artifacts will find their place in the cultural layer.

Paradise Network, however, represents a new turn in Recycle’s work—from the recycling of classical artworks and archaeological projections of the present into the future to an appropriation of virtual reality. Recycle has discovered in social networks features of a brand-new social system, with its own laws, customs and rituals. Our era differs from others in that it dwells not only in real but also in virtual space. «It is neither material nor spiritual, and yet it promises the individual — or rather, his or her ‘profile’—eternal life by adopting the functions of religion. None of the data entered in Facebook is deleted, and sometimes the pages of users who vanished long ago continue to send messages. Sometimes, this profile also gets spam; it continues to have ‘friends,’ exchange ‘likes,’ and so on,» argues Recycle. The laws of social networks have become something like the commandments of the twenty-first century: a person who violates them is denied access to eternal life within the network. One of the principal symbols of this world and its inhabitants is the letter f—the first letter of the word Facebook, which Recycle has turned into a gigantic installation.

Recycle Art Group

Andrey Blokhin (born 1987, Krasnodar) and Georgy Kuznetsov (born 1985, Stavropol) graduated from the Krasnodar State Academy of Culture and Arts in 2010. They live and work in Krasnodar.

Recycle’s first solo exhibition took place in Moscow at M’ARS Centre for Contemporary Arts in 2008. It has since had seven solo shows and exhibited in such large group projects as Russian Povera (Perm Museum for Contemporary Art, Perm; ARTPLAY Centre for Design and Architecture, Moscow); Dior: Under the Sign of Art (Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow); Conservation, a public art project in New Holland (St. Petersburg); Glasstress, a parallel program of the 54th Venice Biennale; and Futurology (Garage Center for Contemporary Culture, Moscow).

Recycle has garnered repeat nominations for the Innovation Prize and the Kandinsky Prize. It was awarded the latter prize in 2010 in the «Young Artist: Project of the Year» category.

Anna Zaitseva: Your new project is called Paradise Network, and I think it opens a new theme in your work. Previously, a central (albeit not the only) theme in your work was the recycling of classical artworks, mostly drawn from Western European art. In one way or another, you worked with the historical «source code». In Cultural Layer, the project that immediately preceded Paradise Network, you moved directly to the present and attempted to show us an «archaeological» projection of the present in the future. And now you have taken on virtual reality — computerized reality in general and Facebook in particular.

Recycle: Cultural Layer really did pave the way, and at some point it was reborn as our current project about the modern miracle of the social network, in which we saw features of a brand new social system, with its own laws, customs and rituals. Here, as in Cultural Layer, we are interested in the question of what from our time will survive in history. Our era differs from others in that it lives not only in real, but also in virtual space. There is the old stereotypical opposition between material and spiritual substances, but the realities of life today show us there is a third dimension. It is neither material nor spiritual, and yet it promises the individual — or rather, his or her «profile» — eternal life by adopting the functions of religion. And it is not just a matter of memory, but indeed of eternal life. None of the data entered in Facebook is deleted, and sometimes the pages of users who vanished long ago continue to send messages. Sometimes this profile also gets spam; it continues to have "friends«,exchange «likes», etc. And one of the principal symbols of this world and its inhabitants is, of course, the letter f, the first letter of the word Facebook. Our parents, for example, got a computer almost at the same time as Facebook emerged. But our transition to working with contemporary material has to do, perhaps, with our becoming interested in finding new meaning in what exists now, because no one but your own generation (give or take a few years) will ever see it the way you did. So we decided to take the situation with Facebook and embed it in the existing architecture of the myth of eternal life, a myth people have always needed.

AZ: And what is your personal attitude towards the new forms of immortality offered by the Internet? Are you users of these forms? Are you for or against them? Or do you take the neutral stance of observers?

Recycle: W e have a really simple answer to those questions. The key task is to show viewers what exists now. Take it, reduce it to an absurdity and show it to people: «It can be this way, folks». But this doesn’t mean we like it.

AZ: I think in this show you have had to face a new challenge. Previously, your «source codes» had a material nature, and recycling them also resulted in a material object as output. Your playing field was a certain thematic shift (usually bound up with the transfer of classical themes to the present) and/or the material support. Although as I see it, this whole story was complicated even then by the fact you were actually working with artworks that already gone through the first phase of recycling. You chose works that had already been processed by the collective consciousness, had become part of it, works that had passed through the mass reproduction machine. Whether we are talking about the Pieta or The Last Supper, people are probably more familiar with them from reproductions than from the originals. With your gesture of artistic recycling, you gave back volume, materiality and objectness to these works, and thus returned them to the museum hall from the media realm. Your work with mass-produced, everyday materials, which you shifted from a «vulgar» context into the context of art, was built on the same principle.

The new challenge I began talking about is bound up, I think, with the fact that now you have chosen something intangible — virtual reality — as your source. You work with it, however, not merely in material forms, but, I would say, in deliberately weighty, monumental forms.

Recycle: The first object — the object with which Paradise Network began, in fact — was The Letter F, and in our works we really do proceed to a large extent from the material aspect, although now, perhaps, it is not so decisive for us anymore. For example, the first works we did as the Recycle Art Group were made from plastic and styrofoam. We didn’t have a lot of money, so we just took materials that were available and attempted to obtain certain visual qualities from them. Where, for example, did the plastic netting come from? We had stopped at a supermarket and accidentally saw it there. We tried melting it with a hair dryer, which was basically a strange thing to do, but it worked for us. Then we went to the supermarket again, but it turned out there was no more of this netting available in Russia; it had to be ordered from Italy, but you had to order a whole container, not just a little bit. As a result, we did a whole show based on the netting, one of our first. That was a kind of exercise. At some point, our materials began to change, and we started to get a feel for them. And when you begin managing the material, rather than it managing you, you go to a new substantive level, because you know exactly how to do it. But the material still keeps prodding us even in this «substantive» direction: we remain perfectionists when it comes to form. Our pieces sometimes look shabby and scruffy, but you would not believe how we pull it off! We have, for example, a special soiling agent to make rubber appear naturally old.

Getting back to The Letter F and the other new works for Paradise Network, we were interested by the allusion to certain archetypal foundations, in particular, para-architectural foundations. The simplicity of their structure is what attracts us. All places of worship are based on archetypal foundations and built around simple shapes: the cross, the cube, the rectangle, etc. So The Letter F, for example, came out severe rather than flowery in our rendition. Actually, the stark font design of the original Facebook also fit well with this idea. Everything added up here, and what we like about this work is the fact it all came together naturally. The more coincidences of this kind, the better.

AZ: Another key piece in this project is, of course, Tablets of the Covenant.

Recycle: Yes, the Tablets, on which the modern Ten Commandments were inscribed, the commandments whose observance guarantees immortality. The principal commandments begin with the words «You shall not . . .» and are directly analogous to the real commandments of social networks. After all, if you violate Facebook’s terms of use, it will block your page and thus cut off access to the eternal life within the network.

AZ: At the beginning of our conversation, you mentioned that the main question for you in this project was what from our time would remain part of history, i.e., the future. Do you think virtual reality has a chance of finding a place in the «cultural layer»?

Recycle: It will take the same place as, say, the ancient Greek gods. Its material shell — the gadgets — will survive. They will be preserved in the soil’s cultural layer the same way as amphoras, however we dispose of them, no matter what we try and do with them. And here we are engaged in playing with the archaeological context. After all, when we talk about, say, ancient Greece, about their gods, and so on, we largely base what we say on archaeological excavations. None of us was a direct witness of the era, and we are forced to undertake its reconstruction — a reconstruction that is always an adulteration, because it is always determined by our political and other contexts.

AZ: Since we are talking about the problems of archaeology, it is quite interesting to apply this to your work. Such works as Archaeology and Petrified Supermarket could be interpreted as critiques of consumerism. Would you agree with this interpretation? Or are they for you adulterations of this critique, which has now become more or less commonplace? That is, are they critiques of this critique of consumerism?

Recycle: There is, of course, a degree of irony and sarcasm in our works, and we like that there is a certain ambiguity in this case — either it is a critique, or it is a critique of the critic. It perhaps really is a case of both the one and the other here.

AZ: You are also clearly fascinated by the adulteration of materials. For example, Petrified Supermarket, which we have already mentioned, looks as if it was made from concrete, but in fact it was made from polyurethane.

Recycle: Yes, because, first, concrete cannot be recycled the way polyurethane can; and second, because polyurethane can last three hundred years or so. It is that same ambiguity that attracts us here — both the work’s durability and the fact it can be recycled into something if we so desire. It happens that you’re making a piece, but then you realize nothing will come of it. So you turn it into something useful, something with which, say, you can prop open a door at home. For us, it is vital not to be afraid to «delete». And to remember that art, like the whole world, is not forever. It is also produced from materials . marble, oil, canvas, etc. . and if something happens with the world, there will be nothing left of art, either. And yet recycling is still a form of immortality — apart from the social networks.