Retrospective

Dmitry Baltermants. The principal clock of the state. Red Square, Moscow. 1964. Artist’s print. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

Dmitry Baltermants. Close combat. Near Moscow. 1942. Artist’s print. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

Dmitry Baltermants. Attack. Near Moscow. November 1941. Artist’s print. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

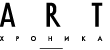

Dmitry Baltermants. Testing of the new ZIS-110 automobile. 1949. New print from original negative. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

Dmitry Baltermants. ‘Quiet hour’ in a kindergarten. 1950. Artist’s print. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

Dmitry Baltermants. ‘Cutting through’ to build Kalinin Avenue. 1960. Artist’s print. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

Dmitry Baltermants. From the ‘Kolia Lives in Moscow’ series. 1960. Artist’s print. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

Dmitry Baltermants. Pipes for a pipeline. From ‘Along the Ob’ River’ series. 1971. Artist’s print. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

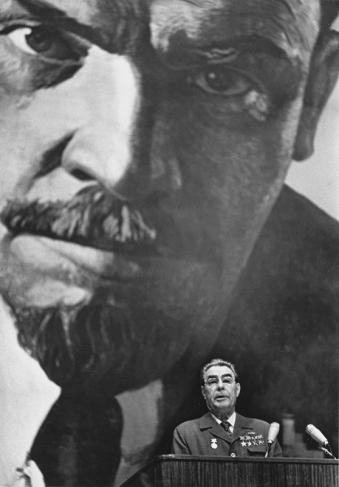

Dmitry Baltermants. Without looking back (Two Ilyichs). Moscow. October 1972. Artist’s print. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

Dmitry Baltermants. Moscow. 1960s. Artist’s print. Museum ‘Moscow House of Photography’

Moscow, 5.07.2012—14.10.2012

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Red Army Captain Baltermants, graduate of the Mechanics and Mathematics Faculty of the Moscow University and lecturer on mathematics at the Military Academy, got his first professional photo assignment in 1939 from the central Soviet newspaper «Izvestia». He was dispatched to shoot the arrival of Soviet troops in Western Ukraine. The result was so impressive that he was promptly offered the post of staff photographer by the biggest and most influential Soviet daily. Few people would have bartered the brilliant promise of an academic career with military rank for the vagabond life of a photo reporter, but Baltermants made his choice with no hesitation.

For the press

With his first professional reports Dmitry Baltermants successfully met the demands of the new age. Right behind him, however, was the great period of the Soviet Avant-Garde, represented by Aleksandr Rodchenko, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vsevolod Meyerhold, Sergey Eisenstein and others. As early as 1926, at the age of fourteen, Baltermants began to work as a typesetter for the «Izvestia» press; he also tried it out as a projectionist and assistant of architects and professional photographers.

Since June 1941 Baltermants became a war correspondent for «Izvestia» newspaper, reporting on the battles of Moscow, Crimea and Stalingrad. In 1943, after an editor’s mistake resulted in wrong titles for his photos, which were inadvertently sent to print, he had to go to a penal battalion, and survived by a miracle. He was «rescued» by a grave wound, nearly losing his leg. After hospital treatment, in 1944 he returned to the front as a photographer, working this time not for «Izvestia», but for an army paper called «Na razgrom vraga», shooting military operations in Poland and Germany. Most of his wartime pictures only came to light during Khrushchev’s «thaw», while the famous «Grief», which brought him world renown, was first printed in the USSR in 1975, thirty years after it was taken.

Back from the front a bemedalled veteran, with thousands of negatives and hundreds of printed works, Dmitry Baltermants was long looking for a job in vain. The penal unit stained his biography, while during the mounting campaign against «cosmopolitism» his Jewish ancestry closed the doors of Soviet periodicals, even those where his oeuvre was admired. Finally the risk of hiring him as a photographer was taken by the poet Aleksey Surkov, chief editor of «Ogoniok», the leading illustrated magazine selling millions of copies. It was there that Baltermants worked until his death in 1990, heading its photo section since 1965.

Baltermants embarked on his professional career at the time when the USSR was already being sealed off by the «iron curtain», which isolated Soviet art from the rest of the world. At this period photography turned from a respected and popular art form into a lackey of the ideological machine, nearly losing its artistic status. Baltermants was among the few photographers who proved successful both at home and abroad, and that for almost half a century. In Russia millions of «Ogoniok» readers decorated the walls of their dreary communal flats with covers carrying his photos. Outside the USSR Baltermants often took part in international exhibitions and sat on prestigious juries of world photo contests at the time when the very notion of going abroad was almost beyond the physical existence and mentality of Soviet citizens. Despite the fact that by Soviet standards Baltermants’ career was a huge success — he went on shooting, publishing and exhibiting widely, and was allowed to work abroad — he was never quite a Soviet photographer. Brilliant professional skills, impeccable sense of composition (while Rodchenko invented diagonal composition, Baltermants the mathematician was a virtuoso of the horizontal), as well as his innate aristocratism enabled him to remain an independent cosmopolitan artist, one that had normal relations with the Soviet regime and never tried to pay anyone back. Even in his most lyrical images he managed to distance himself from the subject. Accordingly, most of his works represent not merely a photo archive of Soviet history, but a philosophic metaphor of his time, looking forward to the future.

Baltermants was equally good at photo reports from the front, staged or semi-staged stills praising the heroic labours and achievements of the Soviet people, or at landscapes and portraits. He did not disdain to resort to collage, inserting heavy clouds into war photos to enhance the tragedy of the events he captured. In Soviet photography retouching was traditionally used to obliterate unwanted figures from history. Baltermants did the opposite: deliberately enlarging the stature of the leader, he glued figures of Communist Party VIP’s onto the pre-shot platform of the Mausoleum, where Soviet grandees lined up during celebrations. Then he photographed the collage, so that his «ideal compositions» straightened out the ranks of Stalin’s closest followers, each of whom strove to attain the best possible place in relation to the «leader of the people». On one occasion Stalin has noticed that something was wrong with these shots, and demanded an explanation. Fortunately, the issue was settled without serious consequences.

Portraits of politicians make up a special chapter in the oeuvre of Dmitry Baltermants. He portrayed General Secretaries of the CPSU, Stalin and Khrushchev, Brezhnev and Andropov, Chernenko and Gorbachev. He observed Soviet leaders without slavish fear, without irony or compassion. He saw them with the eyes of a free man who was able to capture not so much matters of protocol, but symbolic moments, which revealed the personality of those who embodied the age, as well as the age, which manifested itself through their personality.

Baltermants was aware of the legacy of Russian photographic Avant-Garde, and of world photography at large. He made the acquaintance of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Douaneau, Marc Riboux, Joseph Kudelka and other great masters of the latter twentieth century. On the one hand, this strong, clever, wise, courageous and handsome man skilfully created and supported the basic myths of the Soviet regime about the life of the mightiest and happiest people on earth; but, on the other hand, he most ruthlessly stripped reality of its myths, stressing in his photos the common human pains and joys, which do not depend on geographical borders and social structures.

Olga Sviblova

Director

Moscow House of Photography Museum

1912, 13 May — born in Warsaw, Poland.

1915 — after his parents’ divorce and his mother’s remarriage the family moved to Moscow.

After graduating from school, in order to support his family, Dmitry worked as a baker’s boy, then an architect’s assistant, projectionist and typesetter for the newspaper «Izvestia».

1935 — 1939 — studied at the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics, Moscow University; began to work as photographer for several newspapers and magazines.

1939 — served as officer in Red Army, teaching mathematics at the Military Academy in Moscow; as a free-lance «Izvestia» correspondent he recorded the incorporation of Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia into the USSR.

1940 — joined the staff of «Izvestia».

1941 — 1943 — worked as «Izvestia» photographer at the front, recording the defence of Moscow from the Nazis and military operations in the Crimea and Stalingrad. Due to editorial mistake resulting in a wrong caption to one of his photos, Baltermants ended up in a penal battalion and was gravely wounded.

1944 — 1945 — war photographer with the Red Army newspaper «Na razgrom vraga»; recorded military operations in Poland and Germany.

1945 — 1990 — worked for «Ogoniok» magazine, published by the Central Committee of the CPSU; this was the leading illustrated magazine of the Soviet period with a circulation of several million. Political and economic history of the USSR from Stalin to Yeltsin was represented in «Ogoniok» by the photos of Baltermants, whose name became known to virtually every Soviet family.

1960 — 1990 — numerous one-man exhibitions in the USSR and abroad, including France, Italy, Great Britain, Hungary, Finland, USA etc.

Since 1965 Baltermants was member of «Ogoniok» editorial board, headed its photo section, and also engaged in public activities.

1970 — 1990 — chairman of the photo section at the Union of Friendship Societies.

1985 — 1987 — member of the jury, World Press Photo.

1990, June — died in Moscow.