Concentration of the Image. 1920s — 1940s

Eleazar Langman. Water jump. 1932. Author's silver gelatin print. Private collection, Moscow

Eleazar Langman. Khleborob collective farm. 1930. Author's silver gelatin print. Private collection, Moscow

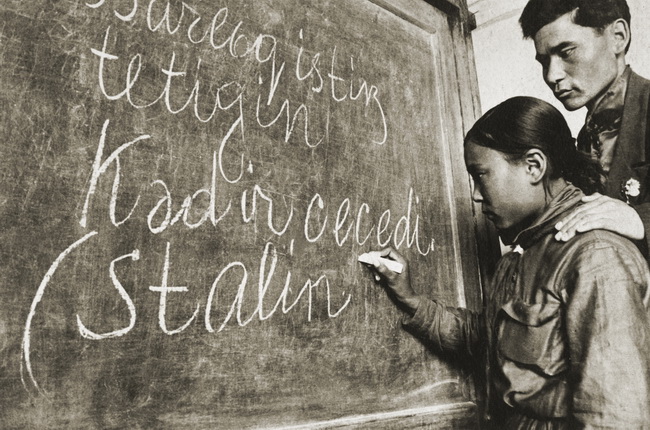

Eleazar Langman. In a Kazakh school. 1934. Author's silver gelatin print. Private collection, Moscow

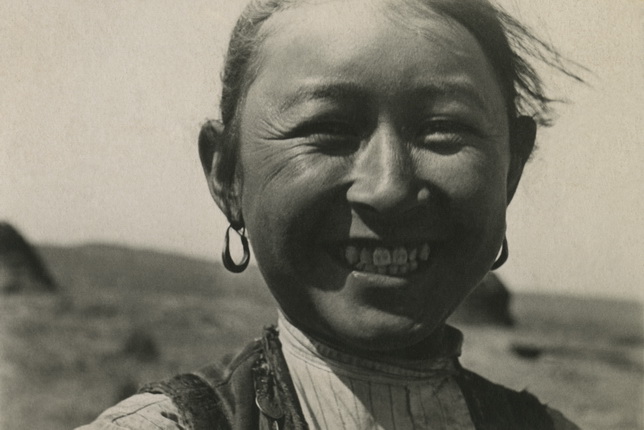

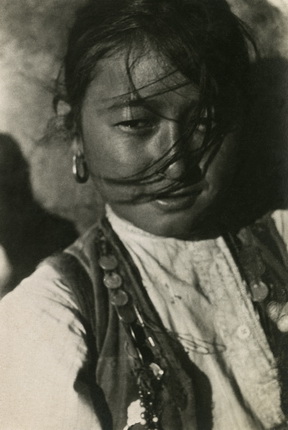

Eleazar Langman. Portrait of a girl. 1934. Author's silver gelatin print. Private collection, Moscow

Eleazar Langman. Portrait of a girl. 1934. Author's silver gelatin print. Private collection, Moscow

Eleazar Langman. Ilambaev and Kuzishtabaev. 1934. Author's silver gelatin print. Private collection, Moscow

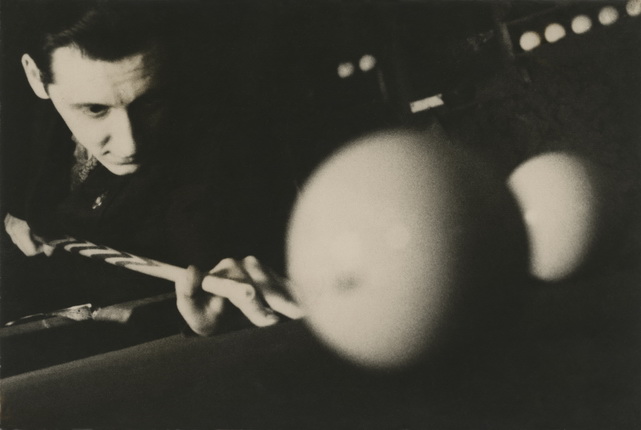

Eleazar Langman. Game of billiards. 1928-30. Author's silver gelatin print. Private collection, Moscow

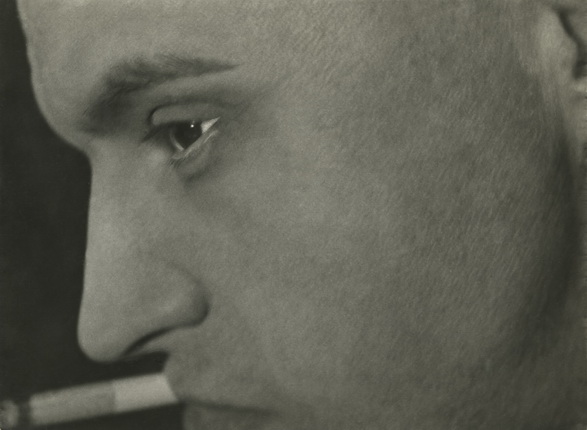

Eleazar Langman. Alexander Rodchenko with a cigarette. 1930. Author's silver gelatin print. Private collection, Moscow

Eleazar Langman. Traffic controller at the corner of Gorky and Gruzinskaya Streets. 1935. Author's silver gelatin print. Private collection, Moscow

Eleazar Langman. Evening on Tverskaya Street. 1935. Author's silver gelatin print. Private collection, Moscow

Eleazar Langman. Mostorg. 1930s. Author's silver gelatin print. MAMM collection

Eleazar Langman. Parachute tower. Gorky Central Park of Culture and Leisure, Moscow, 1939. Author's silver gelatin print. MAMM collection

Moscow, 18.07.2013—8.09.2013

exhibition is over

Share with friends

As part of the programmers ‘Classics of Russian Photography’ and ‘The History of Russia in Photographs’

For the press

Eleazar Mikhailovich Langman (1895-1940) remains one of the most mysterious figures in the history of Soviet photography. In the early 1930s passions raged around his name and those of Alexander Rodchenko and Boris Ignatovich, who together formed the core of the October photographers’ association. Langman was accused of adherence to formalism, of leftism and deliberate ‘obliqueness’ in his frames.

The master’s archive of negatives, photographs, documents and manuscripts (he published articles in Soviet Photo) has apparently been lost, since in the last years after the divorce from his wife Langman had no permanent refuge and moved from one photo laboratory to the next. A catalogue for the 1935 exhibition ‘Masters of Soviet Photo Art’ published biographical details that to this day are practically the only source of information on Langman.

‘Born in 1895, in Odessa. Studied at the Odessa Art College, the Kharkov Polytechnic Institute and Conservatoire (violin class). Played in orchestras and gave concerts in agitprop brigades. In charge of military welding work on the former Volgo-Bugulminskaya Railroad. Worked for the architect A. Langman (uncle of E. Langman — A.L.), author of projects for the Dynamo Stadium and House of the Labour and Defence Council. Also participated in poster work.’

From 1929 to 1930 Langman was photojournalist in the ‘Ignatovich brigade’, taking shots for the newspaper Vechernyaya Moskva. This period saw the formation of his signature quality, the desire to surmount visual clichés of photographic composition at any cost.

‘E. Langman belongs to those who search for new dynamic form in the art of photography,’ continues the author of this article, probably Lev Mezhericher, who also compiled the ‘Masters’ exhibition catalogue, ‘and moreover he is one of the most extreme examples. The creative development of E. Langman has been greatly influenced by his encounter and joint work with B. Ignatovich. He was among the most active members of the creative group October. In his work he proceeds from the formal principles of A. Rodchenko, but has devised his own individual style. In his words he is searching for a ‘new revolutionary form’ to convey Soviet subject matter. His characteristic feature of compositional treatment is rationalism, with distinct accentuation of specific elements in the shot, precise linearity of arrangement, foreshortening and rich content of the frame around the photographic image.’

In 1930 the photo section of the October association published its programme in 8 clauses, stating that photography is one of the most refined methods for influencing the wider public. ‘By recording facts that are socially orientated and not staged we disseminate propaganda and illustrate the struggle for socialist culture’. This idea of showing facts with a social message gave rise to a whole series of shots that can conditionally be described as ‘old’ and ‘new’. A horse-drawn cart was photographed in contrast to a new truck. Churches are contrasted with a club, drunkenness with sport.

‘We are absolutely opposed to staging,’ wrote the authors of this declaration.

‘We are against [...] sugariness, [...] jingoism,’ they continued.

They believed that photography would supersede the old techniques of painting. They promoted the zeitgeist, high quality, technicality and the expressiveness of the material conveyed as artistic criteria. In addition they proclaimed that all their activities were devoted ‘to the goals of the proletariat’s class struggle for a new communist culture’.

All these theses were supposed to convince party organs and critics that the photo section of the October association had the most politically correct precepts.

Titles of Langman’s photographs from the early 1930s serve as a clear indication of the times. In October’s most active period, from 1930 to 1931, the year of the highly controversial exhibition at the House of Printing after which devastating articles on formalism appeared in October and Proletarian Photo, many of Langman’s images bore titles with literary associations. For instance, ‘Old and new Simonovka’ (the area around the Simonovsky Monastery in Moscow), ‘Gymnastics by radio’, ‘Time study specialist at a teaching-experimental state grain farm’, or the very mysterious ‘You give 1040’, referring to 1040 machine tractor stations. Ignatovich has the same type of title — his well-known image of tram controllers at the Dynamo plant was dubbed ‘We are being liberated from foreign dependence’. Literary captions deliberately defined the political or progressive technical context for perceiving a photograph. An oblique shot of camels with carts of grain was paired against a similar diagonally slanted shot, albeit in the opposite direction, of a tractor train delivering grain to an elevator. Thus in Langman’s photo ‘Two means of transport’ the old is contrasted with the new and technically more powerful.

However, a ‘correct’ title did not always help. When criticism of October was at its height the magazine Proletarian Photo stated: ‘...we will mercilessly resist the present trial runs of October’s creative method, where form suppresses content, where lack of content (in fact a class-orientated content alien to us) is veiled by daring captions.’

‘There is no reason to contest the quality of the captions. They are fine. These are some of the slogans with which the USSR proletariat progresses to victorious completion of the five-year plan. However, aren’t these captions merely a cover for the ideological mediocrity of October’s photographic output?’

Among other members of the October group Langman can be seen as the most extreme, open and courageous experimenter. In comparison Rodchenko is more classical, Ignatovich more of a storyteller in his reportages and Vladimir Gryuntal more cautious with his foreshortening and angles. None of them have such an expressive foreground as can be found exclusively in the photographs of Langman.

Fortunately for Langman, despite sharp criticism in the professional press and the demise of October he continued to collaborate with VOKSOM, where he joined a jury selecting photo exhibitions for Europe and America and continued assignments for the Izogiz publishing house. In 1932 he began shooting in Moscow for the photo album-folder ‘From Merchants’ Moscow to Socialist Moscow’. This was psychologically important — the feeling that rather than being an outcast, he was a group member among like-minded people who carried out a specific, necessary and socially justified task. As well as Langman, Ignatovich, Saveliev, Kozachinsky and Rodchenko photographed Moscow for the folder.

On commission for Izogiz Langman went on trips to photograph the state farm Gigant, the construction of new factories in Donbass and the Dynamo and Electrozavod factories in Moscow. Some of the images were used for the massive photo album ‘The Industry of Socialism’, designed by El Lissitzky. He participated in brief courses offered by Soyuzfoto, showing young photographers his images and explaining techniques. Consequently he was invited to take part in the exhibition ‘Masters of Soviet Photo Art’ in 1935.

A creative debate was held while the House of Cinema exhibition was in full swing. In a talk entitled ‘Creative Quests’ Langman mentioned that he deliberately began working in photography in 1929, after meeting Rodchenko and Ignatovich. Why had these two photographers intrigued him? Because he had seen an example of how cliché could be avoided, of originality and vividness. ‘For the first time I was confronted by the concept that photography is art.’

‘What did I begin by doing? In my archive there are no Rodchenko-style ‘Cogwheels’ or other purely compositional shots for the sake of an image, a form. That had already been done, there was no point in repeating it. I couldn’t do any better, and had no interest in doing it any worse. One thing was clear to me, that on the basis of the sharp form I had achieved it was possible and necessary to create real and realistic things.’

Langman also explained the origin of ‘obliqueness’ in his photographs, which became in his expression a ‘parable in tongues’, that is, a frequently repeated accusation of formalism. In his own words, obliqueness in his images was a ‘protest against clichés and drabness in photography’.

In the mid-1930s, when ‘obliqueness’ also became a cliché, Langman set himself other tasks. He tried to relinquish ‘obliqueness’ and foreshortening, while preserving compositional expressiveness of the shot. The magazine USSR in Construction devoted to Kazakhstan and the photo album ‘10 Years of Uzbekistan’ featured portraits by Langman for the first time. His viewing point was slightly below, in extreme close-up with a detailed treatment of faces. Due to the montage and final framing of Langman’s photographs on the pages, Rodchenko and Stepanova, the designers of these publications, revealed the sharpness of Langman’s chosen viewpoint, emphasising the contrast between close-up foreground and minute background.

Langman’s images are memorable for their inner richness and calculation. They are created deliberately and this is how we remember them, as the only possible shot providing maximum information. With his small Leica he concentrated information, form and space in each frame.

Alexander Lavrentiev, Sergei Burasovsky

Exhibition curators