Heinz Hajek-Halke. German Experimental Photography 1930—1960

![Heinz Hajek-Halke (1898-1983)

Traumende Fische [End of Dream Fish],

Gelatin silver print

© Heinz Hajek-Halke / Michael Ruetz, Courtesy Augusta Edwards Fine Art.](/upload/iblock/b42/b426fed41f32383647299a77c2f89b25.jpg)

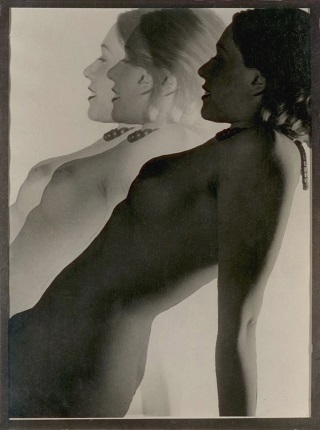

Heinz Hajek-Halke Katarina Berger, c. 1934 Gelatin silver print © Heinz Hajek-Halke / Michael Ruetz, Courtesy Augusta Edwards Fine Art.

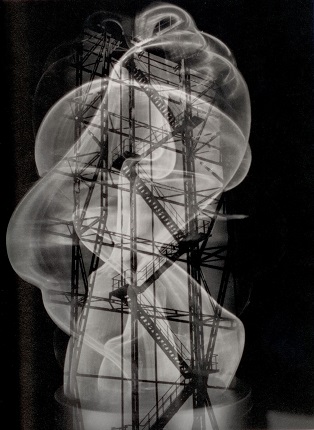

Heinz Hajek-Halke Eisenbahnsignalmaste (Train signals), 1952 Gelatin silver print © Heinz Hajek-Halke / Michael Ruetz, Courtesy Augusta Edwards Fine Art.

Heinz Hajek-Halke (1898-1983) Traumende Fische [End of Dream Fish], Gelatin silver print © Heinz Hajek-Halke / Michael Ruetz, Courtesy Augusta Edwards Fine Art.

Heinz Hajek-Halke Untitled, 1930 Gelatin silver print © Heinz Hajek-Halke / Michael Ruetz, Courtesy Augusta Edwards Fine Art.

Heinz Hajek-Halke (1898-1983) Untitled, Gelatin silver print © Heinz Hajek-Halke / Michael Ruetz, Courtesy Augusta Edwards Fine Art.

Heinz Hajek-Halke (1898-1983) Untitled, c.1946 Gelatin silver print © Heinz Hajek-Halke / Michael Ruetz, Courtesy Augusta Edwards Fine Art.

Moscow, 28.06.2018—29.07.2018

exhibition is over

Share with friends

For the press

Heinz Hajek-Halke. German Experimental Photography 1930–1960

The project presented by Augusta Edwards Fine Art

As part of the Photobiennale 2018 the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow presents the exhibition

‘Heinz Hajek-Halke. German Experimental Photography 1930—1960’.

Heinz Hajek-Halke was born in Berlin in 1898, then spent his childhood and youth in Argentina. After returning to Germany in 1915 he began studying at the Berlin Academy of Arts, but a year later he was obliged to interrupt the course when he was drafted into the army and served on the front in the First World War. After his return he continued his education and graduated from the academy in 1923. In 1924 Heinz Hajek-Halke took up photography and was soon invited to work for the information agency Presse-Photo.

Hajek-Halke worked as editor of the illustrations department and photojournalist while he was also a commercial photographer. He experimented widely with various photographic techniques such as light montage, double exposures, photocollage and photomontage.

In 1933 the National Socialist German Workers’ Party commissioned Hajek-Halke to make a documentary film, but he managed to elude collaboration with the Nazis and went into hiding in Switzerland, where he was involved in scientific photography and biology. When he got back to Germany in 1939 the photographer was called up for military service. During the Second World War he was engaged in aerial and industrial photography for the German army.

After the war Hajek-Halke joined the Fotoform group of German experimental photographers, which exerted vast influence on the development of photography in the second half of the 20th century. In 1951 Otto Steinert, one of the founders of the group, organised under the general title ‘Subjective Photography’ the first of three exhibitions where works by avant-garde luminaries of the 1930s were shown, as well as by young German photographers including Heinz Hajek-Halke. The exhibition attracted great popularity and the term ‘subjective photography’ was used to define the general tendency of German photography during the 1950s to 1960s.

In the mid-Fifties Hajek-Halke returned to the study of technologies that had fascinated him in his youth — the technique of making photograms without the use of a mechanical camera, as well as the creation of photographic abstracts using various photo-laboratory methods he had mastered before the war. For example, Heinz Hajek-Halke was keen on ‘wire montage’, for which he devised flexible wire constructions installed on illuminated rotating platforms. The circular motion of these constructions, coupled with the shift of light at the time of photography, created bizarre complex images.

In 1955 Heinz Hajek-Halke was invited to give lectures on photography and graphic design at the Berlin Academy of Arts. Two of the photographer’s books were published during his lifetime, ‘Experimentelle Fotografie’ and ‘Lichtgrafik’.

The first retrospective of work by Heinz Hajek-Halke was held in 2002 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris with the legendary Alain Sayag as curator, and in 2012 a large-scale retrospective of his oeuvre was organised by the Berlin Academy of Arts.