INDUSTRIAL WORLD THROUGH THE EYES OF ALEXANDER RODCHENKO, IN THE COLLECTION OF THE MULTIMEDIA ART MUSEUM, MOSCOW

аs part of THE BIENNIAL FOTO/INDUSTRIA 2017 (Bologna, Italy)

Vakhtan Timber Mill. Nizhny Novgorod region, 1930

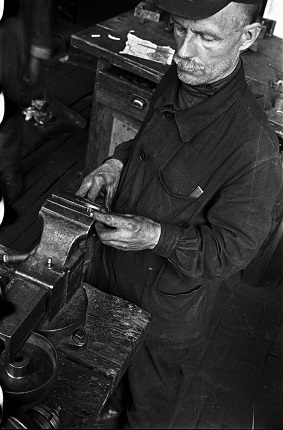

From the ‘AMO automobile plant’ series, Moscow, 1929

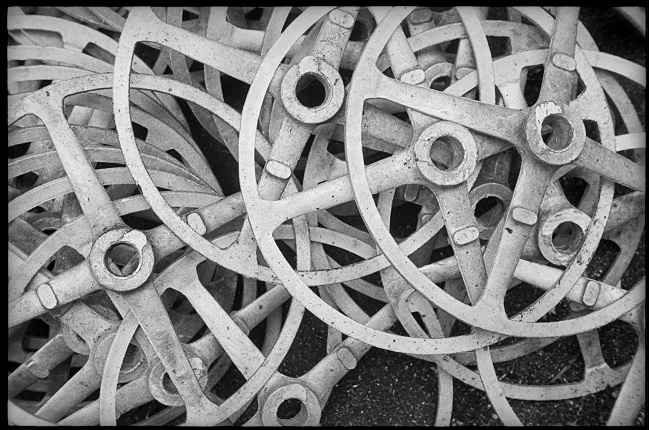

Steering Wheels. From the ‘AMO automobile plant’ series. Moscow, 1929

Production of a Truck. From the ‘AMO automobile plant’ series, 1929

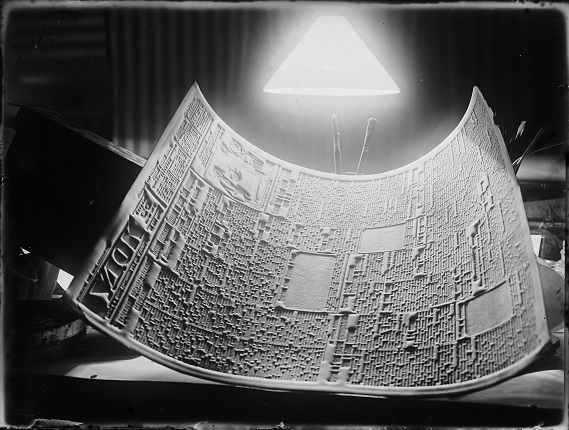

Photo-report about the newspaper ‘Gudok’. Moscow, 1928

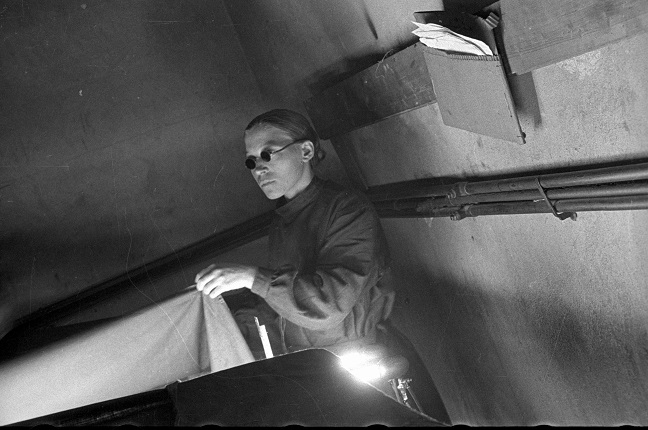

Moscow Electric Lamp Plant, 1929

Moscow Electric Lamp Plant, 1929

Moscow Electric Lamp Plant, 1929

Conveyor at a Distillery. Moscow, 1927

BBVP is Ready. Photomontage for the magazine ‘USSR in Construction’, dedicated to the building of the White Sea-Baltic Canal, 1933

Bologna, 12.10.2017—19.11.2017

exhibition is over

Casa Saraceni Gallery

Via Farini, 15, 40124 Bologna, Italy

Share with friends

For the press

The Institute for Artistic Culture was founded in Bolshevik Russia in 1920. Alexander Rodchenko took an active part in the work of this institute and devised the slogan ‘ART IN PRODUCTION’. Rodchenko headed the metalwork faculty at the institute (amazons of the Russian avant-garde Lyubov Popova and Varvara Stepanova took charge of the textiles faculty, outstanding architect Victor Vesnin the architecture faculty and artist Anton Lavinsky presided over ceramics). Another slogan put forward by Rodchenko for the institute’s activities was ‘Long live production!’ Production and all related work processes were the new religion of Soviet modernism.

The constructivist Alexander Rodchenko created art objects that were to play a functional part in everyday life (Rodchenko’s ceramic sets of the early 20s, the famous Alexander Rodchenko Workers’ Club realised and exhibited in 1925 by the great architect Konstantin Melnikov for the Russian Pavilion in Paris, etc.). From 1923, when Rodchenko took up photography, he turned his camera to everything associated with production, often using the resulting material for his celebrated photomontages.

Faith in production and the constructive transformation of life was a shared belief among all those working in the Russian avant-garde. Production processes became the main theme of Dziga Vertov’s legendary documentary film almanacs. Rodchenko actively collaborated with Dziga Vertov and in particular he created photomontage posters for Cine-Eye and designed text captions for Kino-Pravda. Sergei Eisenstein’s films such as ‘Strike’, ‘October’ and ‘Battleship Potemkin’ are ‘interwoven’ with production processes. The rhythms of the movement of machines and mechanisms fascinated the Russian modernists, whose work looked towards the future. Rodchenko, for whom the future was the meaning of life and activity in the present, wrote: ‘I am so interested by the future that I want to see it immediately, a few years ahead’.

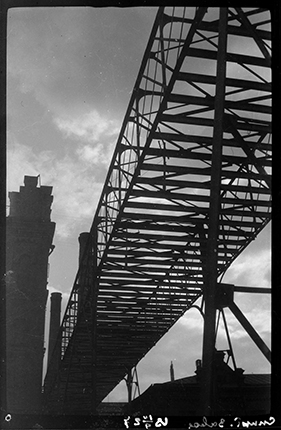

While photographing production, Rodchenko developed a special aesthetics for shooting these images. Unexpected foreshortening and diagonal compositions intensified the dynamics of the frame, and allowed the static image to convey the speed and magical beauty of rhythmic movement. Large-scale perspectives gave the leading role to the production process itself and to the images of people participating in that process.

Rodchenko published his experimental foreshortened pictures in the magazines Soviet Cinema, Novy Lef [Journal of the Left Front], 30 Days, Radio Listener, Let’s Produce!, USSR in Construction, etc.

Literally everything provided material for Rodchenko’s photographic features on labour and production processes: car assembly at the AMO plant, generators at the MoGES power plant, new constructivist buildings erected in the Soviet Union by modernist architects in the 1920s, the manufacture of light bulbs, newspaper production at a printing press, etc.

Rodchenko dreamed of working not just in photography, but also as a cinema director and cameraman. This opportunity presented itself in 1930, when he was commissioned by the Culture-Film factory to accompany a film crew to the Nizhny Novgorod region to shoot the film ‘Chemical Treatment of the Forest’, according to his own plan and screenplay. However, all the equipment issued at the studio proved faulty. Only Rodchenko’s Leica and his Sept compact camera worked as expected (Alexander Rodchenko purchased the latter during his only trip to Paris, in 1925). As a result a photographic series entitled ‘Stacking at the Vakhtan Sawmill’ was produced, instead of the projected film. It was later included in many exhibitions and repeatedly printed in various publications. In the photographs of this series, as in other pictures of production processes, Rodchenko accumulated the principles he developed in his abstract paintings from 1918 to the 1920s.

Like many other figures of the Russian avant-garde, Rodchenko declared that he was eager to serve Soviet production, seeing it as the most important mechanism for implementing the ideas of the Revolution. In 1922 Rodchenko designed himself a special design engineer suit, which was sewn by his wife Varvara Stepanova. Alas, the dreams of the Russian avant-garde very soon came into conflict with the reality of how life and production was developing in the land of the Soviets. The constructivist Rodchenko dreamed of free creative labour by proletarians working for the glory of the future, and in 1933 he was sent to make a photo report on the prisoners who built the White Sea Canal (one of the largest camps of Stalin’s GULAG).

Rodchenko was never a prisoner in the Gulag, but persecution against him started in the early 1930s. The experiments of the Russian avant-garde came to an end in 1932, with the Decree on Socialist Realism as a single form obligatory for Soviet culture in general, for painting, literature, music, theatre, cinema and photography.

At the White Sea Canal Alexander Rodchenko photographed prisoners working in terrible conditions, sometimes to the music of an orchestra also comprised of prisoners. Rodchenko was meant to use his images for photomontages reflecting the heroism of this ‘construction of the century’ for the magazine ‘USSR in Construction’. However, even in photomontages the exhausted faces of the prisoners speak for themselves.

From 1937, the apogee of the Stalinist repressions, Rodchenko was beginning to lose assignments for the Soviet press, and at that time in the USSR the only possible work was at the request of the Soviet authorities. Rodchenko was practically unemployed from the 1940s onwards, and in 1951 he was expelled from the Union of Artists, which completely deprived him of the right to work and participate in artistic life. After the death of Stalin in 1955 Rodchenko was rehabilitated as a member of the Union of Artists, but died shortly afterwards, in 1956. To the end of his days Alexander Rodchenko was never allowed a solo exhibition of his work.