One Man Show

Joel Peter Witkin. Fictional Store Fronts. 2004. Collection de la Galerie Baudoin Lebon, Paris

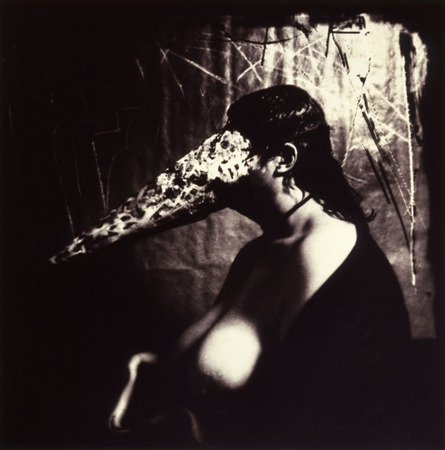

Joel Peter Witkin. Man with dog. 1990. Collection de la Galerie Baudoin Lebon, Paris

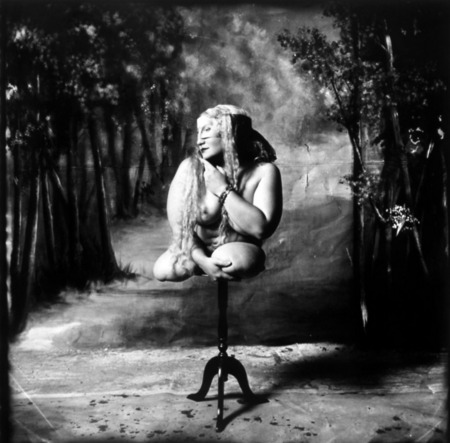

Joel Peter Witkin. Woman breastfeeding an eel. 1979. Collection de la Galerie Baudoin Lebon, Paris

Joel Peter Witkin. Woman on a table. 1987. Collection de la Galerie Baudoin Lebon, Paris

Moscow, 17.03.2005—10.04.2005

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Collection de la Galerie Baudoin Lebon, Paris

For the press

Can we write about Witkin’s works without mentioning once more the eternal, as some think, dispute between art and photography? On the one hand — something lofty, on the other — banal. But this outdated approach only works for those who like cliches and labels and is completely refuted by the last one hundred and fifty years of photographic history, which completely transformed our vision and perception.

Joel Peter Witkin is doubtless an artist. But he does not cease to be a photographer because of that. His works completely preserve their photographic qualities, even though his technique is largely that of an artist — he makes preliminary sketches of his pictures, with a setting built beforehand, transforming the world in his own way and extracting objects out of their usual environment to place them within the limited world of his studio. They could not have existed without photography. It is the only medium which can convey what the artists wants us to see and feel.

However distorted his world might seem, it is always rooted in reality. When Witkin shows us corpses, dismembered bodies, cripples, disfigured creatures, he is not just demonstrating some image, but places before us the concept of contrast, suffering, of death itself... These mutilated bodies are beyond norms, beyond life, but they are not inventions of his imagination. They are here, in front of us and him, made of flesh and blood. They live, their existence was emotionally rich, full of small joys and large misfortunes. They love or have loved. They are loved or have been loved. They are fathers, mothers, lovers, children.

Why does Witkin photograph these things? It is an essential question and some answers will stay eternally hidden in the recesses of his mind. Certain ideas remain inexpressible and grasping them by yourself is not always easier than explaining them to others. In order to comprehend, one must return to the roots, to the years of childhood and youth.

Joel, together with his twin brother Jerome, was born in 1939 in Brooklyn. His mother was a Catholic from Naples and his father — a Jew of Russian origin. There were two brothers; the parents expected three, but one did not survive. Numerous arguments in the family, mostly on grounds of religion, led to the divorce of Witkin’s father and mother. The kids remained with the latter.

At six Joel witnessed an event which he later often recalled. He saw a car accident which resulted in a girl’s head rolling right up to his feet. The first encounter with horror and death will stay with him forever.

The strict religious upbringing deeply influences Joel. He is not satisfied with traditional answers to fundamental questions, which he addresses to himself. His faith is as simple as his life, but it is marked by a degree of mysticism. When he was seventeen Witkin read a newspaper clip about a rabbi, who stated that he saw God. He was disappointed by their meeting. The youngster, who expected vivid revelations, only saw a tired, sleepy old man in the corner of a dusty room. May be photography, which he is now studying by himself, can discover something invisible for the eyes. But the Lord is absent from the developed film. If Joel cannot see Him, the only solution is to create His image by himself.

This is the direction of his future search.

His brother Jerome, who was by then an artist, asked Joel to photograph a Cony Island fair in order to use the shots later for one of his paintings. There Witkin met a person with three legs, the Chicken Lady and Albert-Albert, an androgyne, whom, he will later confess, became his first sexual partner.

People of this kind will from now on be his models, his brothers in suffering, his chosen nation.

For some time he assisted several professional photographers and visited evening sculpture courses at the Cooper Union School, then he was drafted. Witkin, hoping to continue working as a photographer, signed a three-year contract with the army. He expected a routine job — making shots for various documents, but, unexpectedly, he was sent into active service and took part in maneuvers. Here, once more, he encounters death, shooting victims of different accidents and suicides.

From now on this will be his habitual world.

In his incessant travels through the art of the past, Witkin always preserves a sense of respect for mastery and veneration for those artists, who formed his manner. His works have a much deeper meaning than those superficial images the secrets of which are opened to post-modernists. Turning to the past for him is an instrument, not a goal.

A model is something very important in the history of Western art, — painters and sculptors were often inspired by some outstanding work and then included it into their own creations. There are many examples, one of which would be Diego Velazquez’s Las Meninas, which was interpreted by Pablo Picasso and by... Witkin.

Apart from works themselves, some themes return as well, often transcending epochs and fashions. This is especially true about Greek and Roman mythology and the Bible, an inexhaustible source where all facets of human existence are present.

Accepting their language as something universal and lasting, Witkin continues this age-old tradition, adding his personal inventions, his own past and imagination.

Charm? Elegance? When what we see are mutilated bodies, corpses, cut off heads and members? If an artist manages to transcend the boundaries of reality, why cannot art transform death and deformity? We easily imagine an artist holding these motionless bodies and perceiving them not as some impersonal objects, but as something akin to himself. Nothing perversive, nothing scandalous in the treatment of death and deformity. Only compassion. Now and forever.

Alain D’Hooghe