Liable for Prosecution...

Grigoriy Zimin. Untitled. 1920s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection

Nikolai Kuleshov. Untitled. 1930s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection

Nikolai Petrov. Portrait of a Komsomol Girl. 1928. Gelatin silver print. MAMM collection

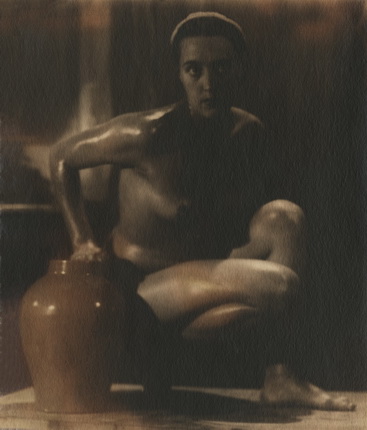

Alexander Grinberg. Untitled. 1920s. Bromoil. Private Collection

Unknown photographer. Tatyana Myakota, 1930s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection

Grigoriy Zimin. Untitled. 1920s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection

Emmanuil Evzirihin. Girl with a paddle. Gorky Central Park of Culture and Leisure, 1936. Gelatin silver print. MAMM collection

Moscow, 26.04.2013—26.05.2013

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Curator: Pavel Khoroshilov

For the press

Pavel Khoroshilov came up with an accurate, polysemic title for an exhibition representing one of the lines in his collection of photography: the feminine in the Stalin epoch. Fleshliness, nude and hidden in industrial clothes, or prozodezhda. The sexual attraction and the drive for social equality that was appropriated by the state allowed the soviet woman to lead the masses in the uniting labor enthusiasm. And the repressive context is also there, of course, with the responsibility for the illegal liberation of the sexual inevitably leading to the measures of social protection through the clauses of the Criminal Code. Time and morals changed, ideological dogmas and ambitious projects of transforming the human being and the world are a thing of the past... Yet, when you peer over black and white photos of famous and unknown masters, it triggers the reaction which is far from what you feel in a museum or an archive: a sort of a live contact with fears and passions, mass drives and a strong desire to retain, no matter what, something of your own, something private, forbiddingly intimate while moving on with the socialized stream of the flesh... There is something that still entrains empathy in these photographs, in short.

Chronologically, the display history starts with the nude of the Russian pictorialists. Actually, they followed the same set of beliefs from the early 20th century in the new, soviet situation. In the last decades of the 19th century the nude photography remains in the basement rooms of both the artistic culture, and of the erotic genre proper with its semi-taboo status and secret life. <...> In the process of developing the awareness of its goals and potential, Russian photography liberated the nude photography as a genre from the functional tethers and obligations of the cultural and moral «basement area». <...> But the social and political situation pictorialists found themselves in was changing rapidly. And it wasn’t just in the trend’s relations with the photo avant-garde, the phenomenon which was forcing it off the stage of current art.

The atmosphere of the time changed irreversibly. No, one couldn’t say that the notion of sexuality was forced out of the social mentality. On the contrary, the discussions focusing on the proletarian Eros initiated by A. Kolontay, L. Reisner, C. Zetkin, the Amazons of Marxist feminism were high on the agenda. <...> But the general line in the struggle for «new, more perfect, full and joyful gender relations» was not worked out yet. Nevertheless the discourse as a whole could be characterized with the words of the same A. Kolontay: «gender relations and class struggle». There was clearly no place for pictorialism in this discourse of the traditional, individualized, «human» sensuousness. <...> Pictorialists continued their work, though. <...> They achieved a new level in the representation of emotionality. In this respect their resources were so profound that Grinberg who belonged to the younger generation of pictorialists dealt with the poetic of optical, emotional, and psychological impressions until 1930s. At the same time he went even further in what I would call the intimatization of the nude as a genre. It is a point of particular importance. The Soviet nude photography followed a radically different vector of development. It was the vector of socializing the flesh. And it combined, quite unexpectedly sometimes, absolutely different objectives.

Marxist feminists mentioned above used the notion of class, and that excluded any individual excesses of sexuality. In the 1930s the state embarked upon the course of a tight control over social morality. <...>

Yet, paradoxically, the creative situation also resisted the individual liberation of the sexual. This phenomenon had its own roots. The classical Russian avant-garde declared, besides other things, a radical cut of the «old-human» (the sexual was naturally a part of it): «Budetlyane» and «Zemlyanity» of the Russian avant-garde, for all their worth, are sexless. Moreover, Malevich’s texts obsessively reiterate «anti-flesh» motifs: meat, corsets, strangling female bodies, fat, wooing Erotes, etc. <...>

The Soviet avant-garde can also be called «anti-flesh» as a whole, with one important correction: it was indifferent to the individual, intimate fleshliness. It was ultimately characterized with the pathos of service, functionality, instrumentality. Surely there was no reason to send these «huge battalions» to fight for the «intimate relations» of individual people. To serve your class is one thing, while to represent the relations of individuals is something quite different. The collective, not the individual body fascinated the soviet photo avant-garde. <...>

The second hypostasis of this exhibition is the female hidden in the industrial clothes, in the uniform. It is the woman involved in production, be it at a factory, at a farm, or at home. It is revealed in the thoroughly selected photo works of M. Penson, M. Kalashnikov, V. Kovrigin, O. Knorring, E. Yevzerikhin, and unknown photo artists. Usually the curators presenting the Soviet body follow a sample path: they showcase the phenomenon of totalitarian photo-eroticism — the art produce with «all the necessary gender attributes» — and sexless products, the evidence of healthy social hedonism unable to arouse individual desires which symbolizes the triumph of a healthy, trained, well organized flesh.

This is how people usually arrange displays devoted to the totalitarian fleshliness. <...> The organizers of this show did not follow the simple path. They don’t limit themselves to the «washed out eroticism», on the contrary, they choose living works when it comes to the nude. And when they turn to the «hidden eroticism» (the fleshliness in the uniform), they display something that is not canonical. It is a rare view upon the specifically female in the time of stereotypes: they are not after functions — a dairy woman, an athlete, a female worker. It is not «shock-worker Sidorova», a dot in the «ornament of masses», but as Krakauer has it, «an individual personality with its own soul». And its own body, we should add. This work is good but not striking on the face of it, this selection of the individual in the ocean of the typological. <...>

Meanwhile the authorities made a sharp turn towards taboos. Hardly had A. Grinberg shifted accents in his nude photography a bit towards intimacy, secrecy, mystery, and he was accused of producing pornography and victimized. Pornography in general turned into a phobia for the regime: it was found during the searches of the apartments of both Stalin’s antebellum «People’s Commissioners of Fear» (Yagoda and Yezhov), and this fact was made public. It was a signal: if pornography was found in the hands of such inveterate foes... In an appropriate situation the nude was treated as a bayonet, the nude was entraining... ah, the nude was entraining still...

Alexander Borovsky