La vie en rose

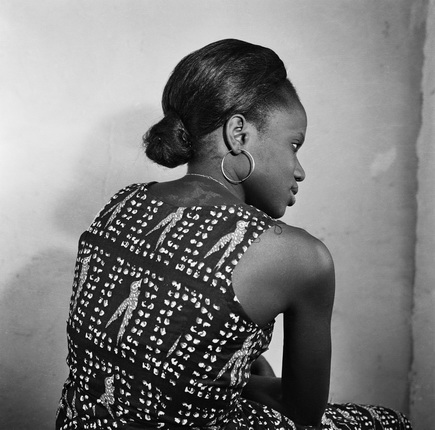

Malick Sidibé. Vue de dos, Studio Malick, Bamako / late 1990s. © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Collection Maramotti, Italy

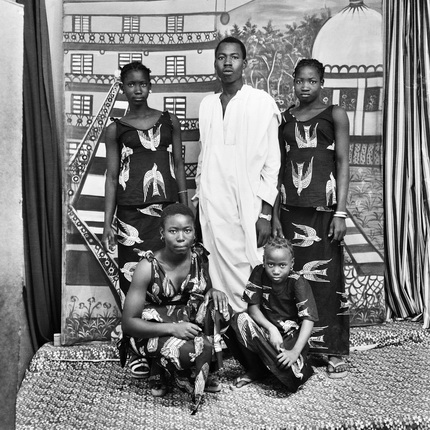

Malick Sidibé. Studio Malick, Bamako, 1977. © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Collection Maramotti, Italy

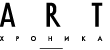

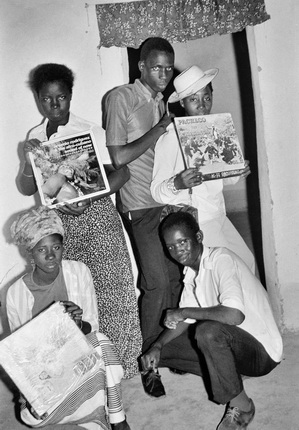

Malick Sidibé. Studio Malick, Bamako, 1977. © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Collection Maramotti, Italy

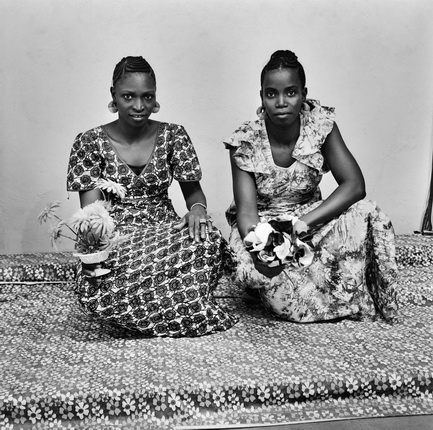

Malick Sidibé. Studio Malick, Bamako, 1977. © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Collection Maramotti, Italy

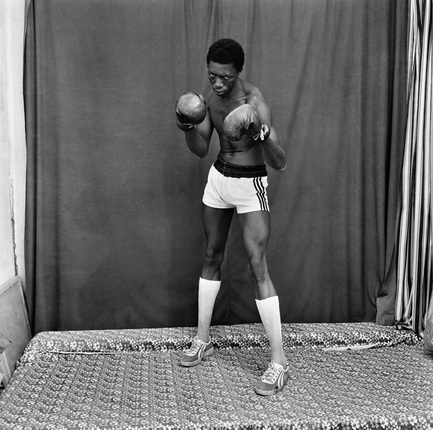

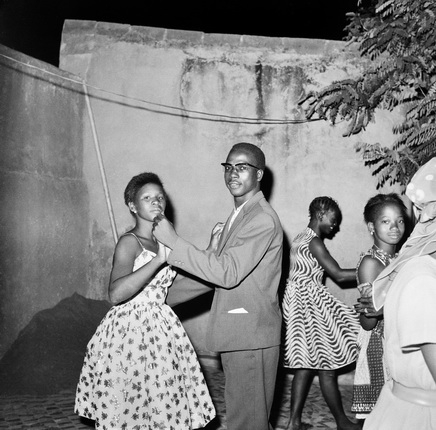

Malick Sidibé. Studio Malick, Bamako, 1966. © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Collection Maramotti, Italy

Malick Sidibé. Devant mon faux bâtiment, Studio Malick, Bamako, 1977. © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Collection Maramotti, Italy

Malick Sidibé. Réveillon de Noël, Bamako, 1963. © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Collection Maramotti, Italy

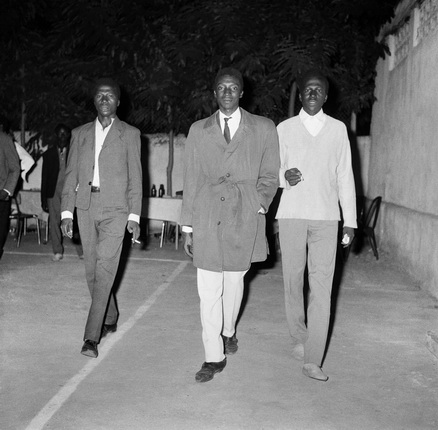

Malick Sidibé. Les Trois Fumeurs, Bamako, 1962. © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Collection Maramotti, Italy

Malick Sidibé. Bal des Aristos, Bamako, 1963. © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Collection Maramotti, Italy

Moscow, 15.03.2013—12.05.2013

exhibition is over

Ekaterina Cultural Foundation

21/5 Kuznetsky Most, porch 8, entrance from Bolshaya Lubyanka street (

opening hours: 11:00 - 20:00, day off - Monday.

Tel: +7 (495) 621-55-22

Share with friends

Сurators: Laura Serani, Laura Incardona

For the press

The exhibition "La vie en rose«presents a selection of circa 90 — mostly unpublished — photographs taken in Mali’s capital Bamako, in the 1960’s —1970’s period. Photographs fully unveiling the magic and excitement of life in Bamako in those years, when the desire of being part of history in its making seemed imperative; images which have made Sidibé world famous: the parties in the 1960’s, studio portraits and a selection of photographs from his archives, which tell us a long stretch of time in the history of Mali.

In 1994 the first Rencontres de Bamako in Mali showed to a small group of Western curators and journalists the existence of a strong, interesting and original African photography, and mostly two great artists, Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, who had been already famous for more than thirty years among the people of Bamako and its neighbouring areas.

The arrival of photography in the African continent followed closely its invention by Daguerre, in France, in 1839. Disdéri’s development of a new equipment heralded the phase of reproducibility of photography. This more accessible and less expensive process won fast success in Europe as it responded to the growing bourgeoisie’s desire for self-representation: studio portrait became the mark of social distinction.

The rapid development of photography was also nourished by the growing interest for images coming from faraway and exotic places and peoples. Photography, accompanying and often replacing the practice of drawing and illustration, turned out to be the ideal instrument to render the reality of new worlds that Europe was starting to explore.

Meanwhile, the first daguerreotypes were already travelling towards North Africa in the late 1839, to move later along the Moroccan coasts towards Ghana (the Gold Coast), Liberia and Sierra Leone. The process, brought along by explorers and travellers, developed at first in the coastal areas, more accessible and thus easier to reach with the necessary equipment, which was fragile and difficult to carry. In order to document and illustrate for reasons of colonial propaganda or social and political control, photography developed soon in terms of technology and practice. And Africans started to rapidly get acquainted with photography from Western technicians and photographers, as one would do with a foreign language; in the main towns, like Freetown, Sierra Leone’s capital, the centre of the British colony, or Accra, Ghana’s capital, the first photographic studios started to open, often thanks to the initiatives of half-caste photographers. It is the beginning of a use of photography which will bring forth a true popular culture of image and a widespread dissemination of the portraiture practice in Africa. This appropriation created a new language which — starting from diverse cultures and influences — would find an originality and authenticity specific to African photography.

After a few decades, having one’s portrait made, fixing for ever important family events became a widespread social trend, as was already the case in theWest. In Africa the portrait’s phenomenon resulted more persistent, conveying a sort of dignity through the representation, a will of control on one’s own image and sometimes a wish of bridging the distance from faraway families. A naïf version of the décors we know so well, like the ones used by the Fratelli Alinari, the painted backdrops that are sometimes still in use in a few African studios are remarkable for their spontaneity and fantasy.

In the production of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, acknowledged masters of portraiture in Mali, these images, which might seem picturesque to us, remain episodic. For Keïta and Sidibé the enhancement of models comes out first of all through the sitting, the attention to characters is still central, and the restraint in the framing exhalts the subject and related accessories (fashionable handbags, transistor radios and even motorbikes) — if present — are just that and nothing more.

For Malick Sidibé the practice of photography has been enriched by his knowledge of painting and classic composition, the search for balance and harmony. His enthusiasm, curiosity and deep humanity give to his images a special emotional charge and a poetry which is rare and unexpected in studio photographs. His models seem always at ease, smiling, although a little intimidated, in front of the camera. Malick Sidibé loves people and exchange; in just a few minutes he has always been capable of striking a privileged relationship with the people to be photographed: «Smile, stand straight, look before you, show your best, have fun, life is short.» This advice might sound almost paradoxical, from the untiring Sidibé, who in the sixties was to be seen rushing through the night from one party to the other to take photographs, and later to develop and print till dawn,waiting for customers to come the next day. Often the Bagadadji studio worked almost 24 hours a day.

Since the 1950’s Malick Sidibé has been the most wanted photographer in town, for his studio portraits and reportages of the nights in Bamako. Thus the most famous living photographer in Africa has assembled in thirty years thousands of negatives which represent an archive of rare richness from a photographic, historical and sociological point of view: the whole town has passed through his studio. Sidibé has portrayed the Malian society caught in its full transformation, between the mid 1950’s and the late 1970’s. In his chronicles of ordinary people’s daily lives, the evolution of customs, ways of life as well as fashions are the visible indicators of the deep changes taking place in society.

If the photographs taken in the studio, where families in traditional dresses, notables in their ceremonial garbs and young people in Western clothes took their turn in the sitting, present an overview of Malian society, where tradition and modernity are present side by side, the images in the exteriors show essentially a group of young people moving away from traditional codes and creating a new identity through the re-processing of Western influxes. Fashion and behaviours evolve, although social and religious values and traditions remain solid.

In the aftermath of Mali’s independence, in 1960, young people knew they were part of an epoch-making moment and a pan-African movement with at last a relevant role, while new prospects and frontiers opened towards Europe and countries in the Soviet sphere. The winds of liberty were blowing over Africa: nights became longer when dancing American and Cuban rhythms and music made many barriers seem to vanish.

The passing of time has also brought changes in fashion, full-flared dresses were replaced by shorts and bell-bottom pants, hand-bags replaced by shoulder bags, LP’s by portable record-players. In recent years Sidibé has come closer to Western photographic production and his curiosity has brought him to make some forays in the world of fashion, while keeping his usual style and approach: magic always lies in making the «belles de Bamako» even more beautiful. After having made a series of photographs for Pennyblack in 2008, the next year, on the New York Times Magazine’s request, Sidibé called again the young people of Bagadadji to sit for him in his studio with Africa’s inspired clothes designed by Christian Lacroix, Prada, Marni, Dries Van Noten... And he won the World Press Photo with these images.

The diffusion of colour photography and later the digital revolution have gradually slowed down the activity of the Studio Malick, but after a period of stop, thanks to Sidibé’s international fame, clients started to come to the studio again, together with the many tourists arriving to Bagadadji by taxi, for a not-to-be-missed visit during their stay in Bamako.

Today with the crisis and the war in Mali everything is changing, and for the moment, the studio’s activity seems to be suspended for a while...

Laura Serani

Text issued from La Vie en Rose — Silvana Editoriale

Project presented by Collezione Maramotti, Italy

«I believe in the power of image and this is why I lived all my life making portraits of people in the best possible way, trying to give back to them as much beauty as I could, because life is a gift from God, and should be better lived with a smile on your face. Too often is Africa’s image linked to pain, poverty, misery, but Africa is not only that, and this is what I have always wanted to depict in my images».

«I am a true witness of the changes in my Country, because photography does not tell lies, at least black and white photography, which I have always done. This is why I strongly believe that my photography is much more truthful, real and direct than any word. It is simple, anyone can understand it, and it tells an epoch, without deception. Humanity has always searched for immortality in painting or poetry, in writing, but in the past only kings and the wealthy could have their portrait made. Photography is a way to live longer, even after your death...».

Malick Sidibé was born in 1936 in Soloba, a village 300 kilometers away from Bamako. In 1955 he graduated in drawing and jewelry making at the Sudanese School of crafts, where he was the first of his course. Young Sidibé became fascinated with photography and decided to stay with Guillat-Guignard as his apprentice, after having received the assignment to decorate the French photographer’s shop. In 1957 he started making his first reportages of parties, christenings and weddings. In 1960 he started his career as a free-lancer and in 1962 he opened the Studio Malick, in the popular neighborhood of Bagadadji, where he continued his activity as portraitist.

At the same time Sidibé depicted the nights of Bamako and the holiday afternoons spent on the banks of the Niger river: Mali had won its independence just two years before and the Country was full of new energy and enthusiasm. News and information went around, films arrived from Europe, India and the United States, but it was mostly music that brought fast and widespread changes with it in Bamako society.

The photographer attended the parties of young people wearing Western clothes and dancing to the music of record players: his photographs depicted joyful youths, full of zest for life and hopes for their future. Night clubs with exotic names were opening everywhere in town and Sidibé was invited to all big events: his fame was so great that if he could not participate, then they would change the time or even the day of the event.

In the late 1970’s, Sidibé decided to focus his activity on studio portraits. After having exchanged a few words with the people to make them feel at ease, Sidibé himself would choose their pose for the sitting, succeeding in grasping the essence of their personality in just a few snaps.

In 1994, during the first edition of Rencontres de la Photographie de Bamako, his portraits were exhibited for the first time together with Seydou Keïta’s works (another great author from Bamako who was about ten years his senior and died in 2001). Western authors and critics discovered their talent. Soon after that Sidibé’s photographs went to Paris, at first at Fnac Etoile , curated by Laura Serani and later at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain; in just a short while museums and galleries from all over the world started exhibiting his works. The author still lives and works in Bamako. Today Sidibé is considered Africa’s most important living photographer. In 2007 the Venice Biennale honoured him with the Golden Lion for the career, awarded for the first time to a photographer. In 2003 he won the Hasselblad Prize in Sweden, in 2008 the ICP Award in New York, in 2009 the prize PhotoEspaña-Baume & Mercier in Madrid, and in 2010 the World Press Photo for the Arts and Entertainment Section in Amsterdam. Many publications and books on his work have been printed in Europe, the United States and Africa.