Retrospective

Mikhail Prekhner. Model aircraft enthusiast. 1934. For the magazine USSR in Construction, 1935, №1. Silver gelatin print

Mikhail Prekhner. Friends. Mid-1930s. Silver gelatin print

Mikhail Prekhner. From the series 'Pushkin Square'. Moscow, 1932-1935. Silver gelatin print

Mikhail Prekhner. From the series 'Pushkin Square'. Moscow, 1932-1935. Silver gelatin print

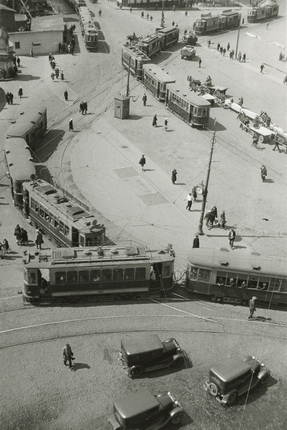

Mikhail Prekhner. Moscow, square near Krasniye Vorota. 1932. Silver gelatin print

Mikhail Prekhner. From the series 'International Commune Nursery'. 1934. Silver gelatin print

Mikhail Prekhner. Narkomzem building. Moscow, 1933. Silver gelatin print

Mikhail Prekhner. Portrait of his wife. Second half of the 1930s. Photographer’s silver gelatin print

Mikhail Prekhner. For the book ‘First Cavalry Army’. 1935. Photographer’s silver gelatin print

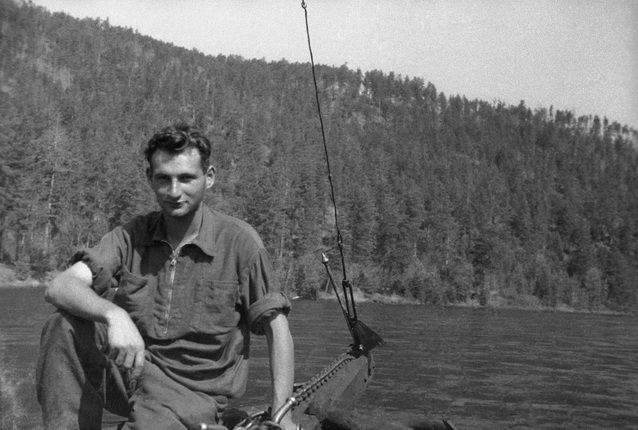

Mikhail Prekhner. Shooting in Oirotia. 1935. Silver gelatin print

Moscow, 29.01.2013—24.02.2013

exhibition is over

Share with friends

For the press

I was born in Warsaw in 1911, into the family of a white-collar worker. In 1914 we moved to Moscow. I was interested in photography from childhood. After graduating in 1928 from the nine-year high school I decided to make photography my profession. I went to work in the editorial offices of Radioslushatel (Radio Listener) and Govorit Moskva (Moscow Calling). After working there as photo correspondent for two years I was appointed as first-category photo reporter at the Soyuzfoto agency. There I was trained as a news photographer.

From December 1931 I worked at Izogiz (subsequently Iskusstvo publishers) on specific large-scale themes for albums. I was actively involved in producing the albums ’First Cavalry Army’, ’Universities’, ’The Red Army’, ’Pioneering’ and ’Socialist Industry’ for exhibitions in Paris and the USA, etc. For the ’First Cavalry’ album, in which most of the photographs were mine, I received official recognition from my publishers.

Beginning in 1932 I contributed to the magazine SSSR na stroike (USSR in Construction). In 1932 these shots were featured in the issues ’Dneprostroi’, ’Khibiny’ and ’Railway Transport’. Thereafter my work was inseparably linked to the USSR in Construction editorial office. I produced special issues entitled ’The Red Navy’, ’Buryat-Mongolia’, ’Pushkin’ (?), ’Happy Old Age’, ’The Far East’, ’Small Towns’, ’Steel’, etc.

During trips to every corner of the Soviet Union I always had to instruct local editorial workers, help format regional newspapers and make wall newspapers at collective farms, Red Army units and factories. In Khabarovsk, for instance, the local newspaper organised a large-scale meeting with the city’s professional and amateur photographers, with whom I shared my experience of working for print publications. I also worked with Pioneers at the House of the Young Technician in Moscow.

From 1933 I participated in all the exhibitions of Soviet photography abroad. Also from that time onwards my photographs featured in dozens of international exhibitions in Europe and America. I was awarded the Grand Silver Medal for my work at the Antwerp International Exhibition in 1938.

I received First Class prizes at exhibitions by Moscow photographers, and at the All-Ukrainian Photo Exhibition in Kiev.

Mikhail Prekhner was only 30 when he died. He was dispatched as press photographer to record the assault on Tallinn in August 1941. While the bombs fell, shy, delicate Prekhner in his dark-blue striped civilian suit took shots of the Russian evacuation on 27 August, the day before the Germans entered Tallinn. He was seen taking photographs as troops boarded the ship under artillery fire, but he himself was in no hurry to embark and continued shooting to the end of the film, as a soldier shoots to the very last cartridge. In his profession the most treasured frame was the last...

There were two Prekhner brothers, Max and Mikhail. On the eve of the First World War their parents brought them from Warsaw to Moscow. Both had a keen interest in photography. In 1920, after finishing school, Max Prekhner began training as a photographer at a vocational college. Mikhail, the youngest brother, was then aged nine. His elder sibling is well known for shooting the 1933 Moscow—Kara Kum—Moscow automobile rally, with Roman Karmen acting as film cameraman. But it was the younger brother, Mikhail, who was invited to take part in the famous 1935 exhibition of Soviet photo art, where the jury included Sergei Eisenstein, Alexander Rodchenko and Alexander Grinberg.

The younger Prekhner’s work made such a favourable impression that the issue of Soviet Photo magazine covering this exhibition (№ 6, 1935) printed a separate article devoted to Prekhner junior, in the feature ‘Profiles of Masters’: ‘He is just 24. But despite his tender age he shows great promise and has made many interesting and significant achievements in his chosen field,’ writes P. Krasnov. ‘The first collection of Prekhner’s work appeared in the journal USSR in Construction, in an issue marking the tenth anniversary of the Buryat-Mongolian Republic. For this issue Prekhner took photographs ‘in tandem’ with M. Alpert, an accomplished press photographer with many years’ experience. Mikhail Prekhner emerged from this unofficially declared contest with flying colours.’

Admittedly, the young photographer was well prepared for the ‘contest’ with Max Alpert. Although lacking specialist training (can many boast of this, even today?), he learned from experience at the Izogiz publishing house. He had begun work there in 1932. At that time Izogiz produced information-propaganda albums, including ‘First Cavalry Army’, ‘Universities’, ‘Red Army’ and ‘Industry of Socialism’. Leading photographers such as Alexander Rodchenko collaborated with the publisher. Notably, Rodchenko participated in preparation of the ‘First Cavalry Army’ album with photographs by Mikhail Prekhner. The publishing house awarded Prekhner official recognition for this commission.

Certainly Rodchenko’s innovations such as the ‘oblique’ slant, sharp camera angle and shots from above or below were very popular. But Mikhail Prekhner was a talented pupil. We need only look at the shot ‘Jump’ in the same issue of Soviet Photo. The naked figure of a boy getting ready to jump, against a background of sky. His back is straight, arms raised and held slightly behind him like wings. Although still motionless, his entire body is taut, tense with the exertion of energy. There are no details, only the sloping board of a narrow platform where the child stands. Prekhner took the photograph from below, and a little behind. As a result the young boy with outstretched arms seems to hover in the sky.

Images of sportsmen are among the favourite themes of Soviet photography. Orderly rows of muscular gymnasts at athletics parades on Red Square, young swimmers and athletes with a stadium in the background symbolised youth, energy, and the country’s optimistic aspirations for the future. Probably Prekhner, too, was aiming for exactly this effect. But strangely enough, an unexpected and by no means constructivist nuance of meaning appears in the photograph, in addition to the characteristic and wholly ‘Rodchenko’ angle. The beauty of the human body, the refined plasticity of movement, the nudity, implied naturalness and proximity to nature are motifs from a very different, certainly not modernist, oeuvre. A human being valued in his own right, not merely a cog in the social machinery.

This calls to mind the interest in ‘plastic man’ prevalent throughout the 1910s and 1920s. Who could forget the barefoot dances by the studio of Isadora Duncan. But plasticity in motion was studied by scientists and photographers, as well as choreographers. An entire choreological laboratory operated at the Academy of Artistic Sciences (GAKhN), but was later dismantled — it was hard to find any ‘depiction of contemporary reality’ in nude studies and dance études. However, in the mid-1920s the Academy managed to organise several photography exhibitions presenting ‘The Art of Movement’. They displayed works by such eminent masters as Nikolai Andreyev, Alexander Grinberg, Nikolai Svishchov-Paola, Moisei Nappelbaum and Yuri Yeremin. It is unlikely the Prekhner brothers, by their own admission ‘keen amateur photographers’, would have missed the sensational exhibitions in 1925 and 1926 of work by photographers from the old, pictorial school. It seems only natural for them to attend, especially since Mikhail would have been 14 and 15 at the time, Max 21 and 22. Whatever the case, in Mikhail’s photograph ‘Jump’ we detect a similar admiration for plastic movement, harking back to classical culture. His little swimmer is more akin to a Greek god than a future aviator.

Curiously enough, indirect proof of the younger Prekhner’s interest in the pictorialists can be found in a passage entitled ‘What the Stands Teach Us’, published in the same issue of Soviet Photo. Recalling that at the exhibition ‘in 1928 ...as a keen amateur photographer I spent hours scrutinising and studying shots by Alpert, Yeremin, Fridlyand and other participants’, he singles out Yuri Yeremin: ‘The images by Yeremin are impeccable and subtle. For a long time Yeremin has influenced my work. Not only amateurs, but all our press photographers can learn something from him.’

It is no surprise that lyricism is seen as a hallmark of the younger Prekhner’s style. ‘Prekhner’s lyricism is not the product of languid frames of mind, it is filled with vernal transparency and great love for man,’ writes P. Krasnov. This lyricism is also picturesque. For confirmation we can turn to the photographic series shot in Pereslavl-Zalessky. Prekhner photographed this in 1940, for the May issue of USSR in Construction, devoted to small towns. It stands to reason that here we see a shot of the Pravda newspaper wall-stand with the Transfiguration of Our Saviour Cathedral in the background. How could he not include a juxtaposition of the ‘old’ and ‘new’? The workshops of the local factory may appear in an uncompromising constructivist style. But the fishermen on the lake, the netted fish and the ancient walls of a former monastery are photographed as if this were heaven on earth.

Of course he was a man of his time. At least, unlike the pictorialists, he preferred to use his Leica instead of photographic plates. ‘Unfortunately he was a zealous advocate of the Leica. And although he wielded it like a true virtuoso, we were obliged to warn him of this camera’s harmful influence,’ lamented P. Krasnov, an admirer of his work. Probably Prekhner absorbed the best features that Soviet photography could offer him at the time. Rodchenko made an accurate appraisal: ‘Prekhner resolved the task in a simple manner — he took the very best from everyone: the prettiness, the long shot angle and lyricism from Yeremin, the laconic subject matter from Shaikhet, and the positions and angles from me. Obviously it was a success...’ However, Rodchenko made the harsh observation in 1936 that ‘Prekhner has produced some good work, but lacks any real creative identity’. In fact this was not so much criticism as an indication that the photographer had scope to develop his skills. As if an eternity lay ahead.

But he had only five years left. In 1938 one of Mikhail Prekhner’s photographs was awarded a silver medal at an international exhibition in Antwerp. It had seemed that his brother was far less fortunate. He served in the air force. In 1938 Max became a victim of political repression. In October 1941 he was mobilised to a penal company as rifleman-photographer. Apparently such duties were listed in the table of ranks. Probably he was unaware his brother was no longer alive. But ultimately fate was kind to the elder Prekhner. Max Prekhner fought to the end of the war, although he was wounded in March 1945. He died in Moscow in 1982. In the city where, back in the 1920s, he gave his brother a camera to hold, for the very first time.

Zhanna Vasilieva