Modernism in Japanese Photography

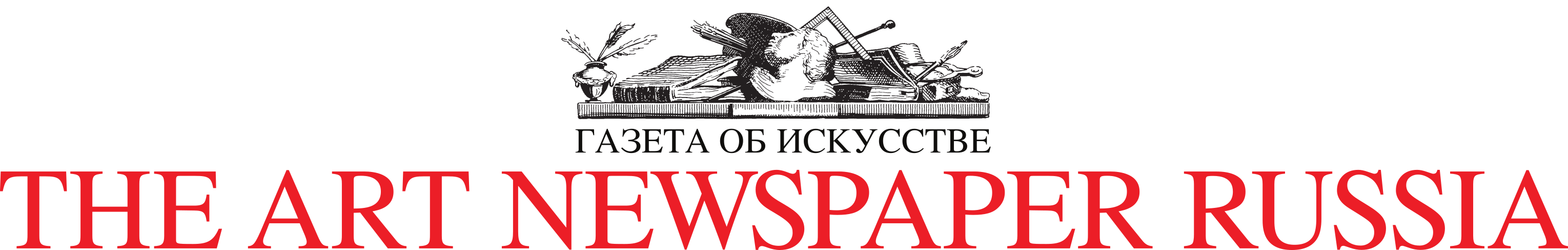

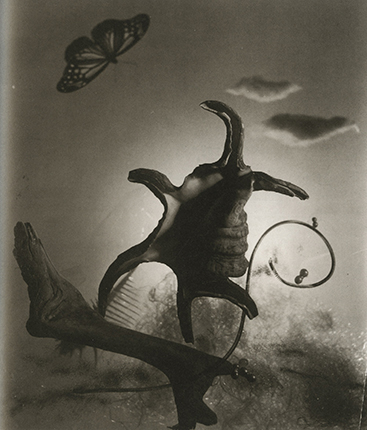

Iwata Nakayama. Futurism Pantomime, 1927. Gelatin silver print. Collection of the Iwata Nakayama Foundation. Courtesy of the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art

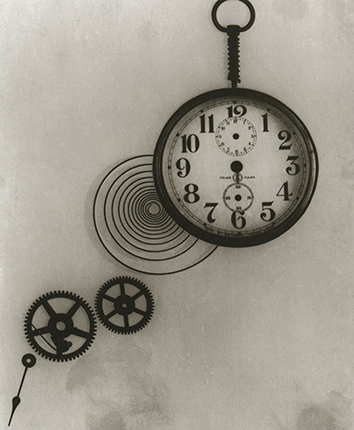

Iwata Nakayama. Japanese Girl, c. 1925 Gelatin silver print. Collection of the Iwata Nakayama Foundation. Courtesy of the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art

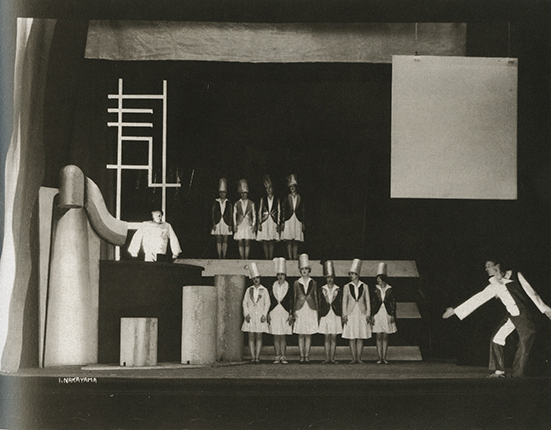

Iwata Nakayama. Composition, 1933 (printing 1996). Gelatin silver print. Collection of the Iwata Nakayama Foundation. Courtesy of the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art

Iwata Nakayama. Woman with Long Hair, 1933. Gelatin silver print. Collection of the Iwata Nakayama Foundation. Courtesy of the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art

Iwata Nakayama. Composition (Lace and Glass), 1930—1935. Gelatin silver print. Collection of the Iwata Nakayama Foundation. Courtesy of the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art

Iwata Nakayama. Creation, 1942. Gelatin silver print. Collection of the Iwata Nakayama Foundation. Courtesy of the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art

Moscow, 18.05.2018—22.07.2018

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Curators: Olga Sviblova, Anna Zaitseva

Collection of the Iwata Nakayama Foundation

Courtesy of the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art

For the press

XII INTERNATIONAL MONTH OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN MOSCOW ‘PHOTOBIENNALE 2018’

Iwata Nakayama

Modernism in Japanese Photography

Curators: Olga Sviblova, Anna Zaitseva

Collection of the Iwata Nakayama Foundation

With the assistance of MEM

As part of the Photobiennale 2018 the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow presents an exhibition of work by Iwata Nakayama, one of the leading exponents of the modernist period in Japanese photography.

‘Possessing sophisticated technique and a subtle sense of form, he made the photographic paper radiate with unprecedented splendour,’ writes Yuri Mitsuda, curator at the Shoto Museum of Art.

Iwata Nakayama was born on 3 August 1895 in Yanagawa (Fukuoka Prefecture). Even as a child he was interested in European art and wanted to become an artist. In 1915 Nakayama began studying at the newly opened Provisional Department of Photography in Tokyo Fine Art School. It was renamed the Department of Photography in May 1923 but closed three years later. During the eleven years of its existence, 47 students graduated from the Department of Photography; Iwata Nakayama was among the first nine of these.

After finishing art school Nakayama was sent by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture and Trade to complete his post-diploma work in the USA. He studied art history at the California State University before relocating to New York, where after a while he established his own photography studio on Fifth Avenue. In the early years the photographer had to seek out his clients by personally making the rounds of large out-of-town houses. In order to attract customers he even issued special coupons. During Nakayama’s ‘American period’ he was mostly occupied with commercial studio images, and only after moving to France did he decide to devote himself entirely to artistic photography.

In 1926 he sold his New York photo studio and moved to Paris, which was the focus of European artistic activity in the time between the two World Wars. Those years in the French capital witnessed Alberto Giacometti’s first solo exhibition and the Second Surrealist Exhibition, as well as publication of Max Ernst’s ‘Natural History’.

Iwata Nakayama’s most important work of this period was a series of photographs dedicated to the oeuvre of Italian futurist artist Enrico Prampolini. In these images Nakayama depicts futurist compositions of geometric forms that demonstrate the radically avant-garde stylistics of Prampolini’s work. Later Nakayama used these photographs for the cover of the Japanese magazine Koga, and included fragments of them in many of his photomontages.

In Paris Nakayama also created his first photogram. Although by then this technique had already been developed in the work of Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy, Nakayama devised his version independently, from his own experiments.

In 1927 Nakayama returned to Japan. The decade spent in the USA and France exerted tremendous influence on the photographer’s worldview and the formation of his artistic style. While acquainted with American and European art, Nakayama resolutely refused to imitate it. He wanted to be on equal footing with European and American artists by creating something fundamentally new, by not trying to copy Western models.

Artistic photography was largely the domain of amateurs in early 20th-century Japan. In general the public were interested in the objects depicted in the image, rather than the photograph as a means of artistic expression. But Nakayama believed that photography can be pure art. It is the camera that creates the picture, he declared, but the artist wields the camera.

‘For a long time I considered photography and painting to be one kind of art, since both work with a plane. But no matter how I improve my skills, I remain infinitely far from Raphael... Instead I began to delve into the beauty and charm of photography, and investigated the possibilities of its materials and instruments... As a result I was able to create artistic photographs that give me a certain sense of satisfaction,’ said Nakayama.

In the 1930s Iwata Nakayama was one of the brightest stars of Japanese photography, although in the period of growing nationalism the fact that he used the camera to express his inner world instead of reflecting objective reality often evoked criticism. Iwata Nakayama nonetheless remained true to his principles.

The Ashiya Camera Club established by Iwata Nakayama was proud of the fact that it ‘valued individuality above all’ and ‘did not create imitative work’. Nakayama believed that the criterion for assessing work should not be its conformity to a certain style, but rather the image must be ‘free of imitation and true to the artist’s concept’.