Photographing the sculptures 1989-2003

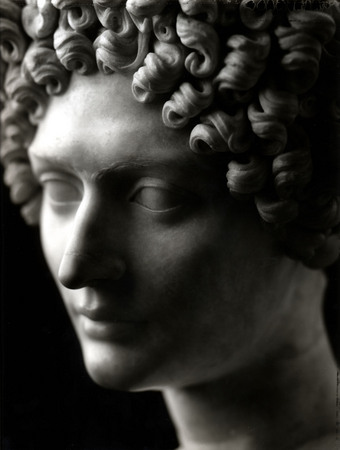

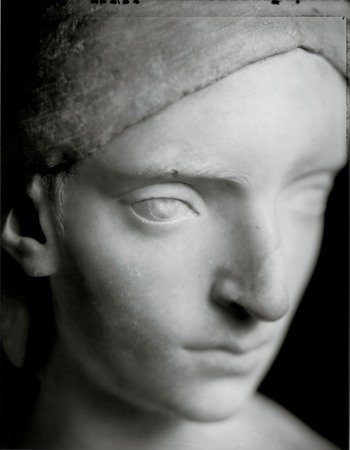

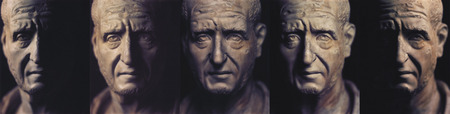

Marco Delogu. From “Ritratti etruschi” series. 1996. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Ritratti etruschi” series. 1996. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Ritratti etruschi” series. 1996. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Ritratti etruschi” series. 1996. The collection of the author, Rome

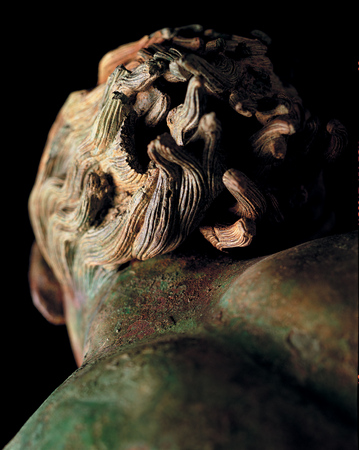

Marco Delogu. From “Il satiro danzante” series. 2003. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Il satiro danzante” series. 2003. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Il satiro danzante” series. 2003. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Il satiro danzante” series. 2003. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Il satiro danzante” series. 2003. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Il satiro danzante” series. 2003. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Il satiro danzante” series. 2003. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Il satiro danzante” series. 2003. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Il satiro danzante” series. 2003. The collection of the author, Rome

Marco Delogu. From “Il satiro danzante” series. 2003. The collection of the author, Rome

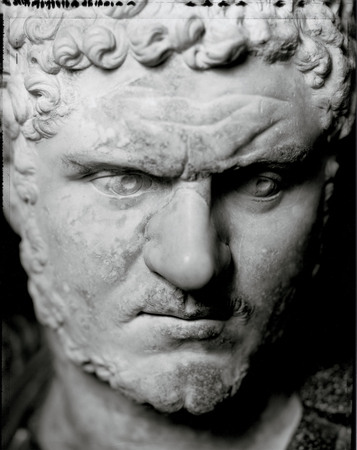

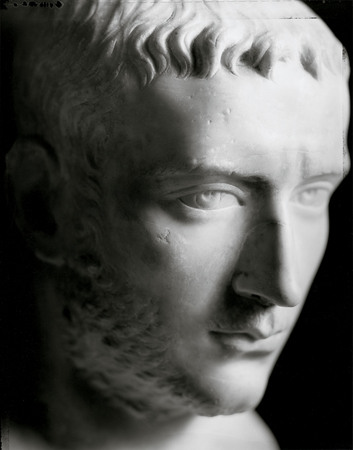

Marco Delogu. From “Traianos” series. 1993. The collection of the author, Rome

Moscow, 19.03.2005—11.04.2005

exhibition is over

Joint association "Photo Center"

8, Gogol Boulevard

Share with friends

The collection of the author, Rome

For the press

This exhibition brings together for the first time a series of portraits of Roman and Etruscan statues taken by Marco Delogu. It was with this first series of portraits of Roman busts that his almost obssessive sequence of work on portraits of faces and groups began. In photographing these statues Delogu expresses the sensitivity of his own fascination with faces, and the relation that light can create between the features of a face and their psychological value, all of which is later transferred to human faces. This work led him to develop many series of portraits of groups of people having in common a particular experience (from the peasants of the pontine marshes, to the prisoners, the Palio jockeys or the cardinals) or else by a common language (such as the series of composers of contemporary classical music).

A common theme of this exhibition is the statue and its portrait. The face that is captured by the photographer has already been definitively fixed in time, but this does not mean that it cannot be reinterpreted. As Geraldine A. Johnson writes «his aim is clearly to interpret rather than to document. Unlike the sculptures that are uniformly lit and give up their visual information to the objective eye of the art historian or museum curator, Delogu’s images are deliberately shadowy and difficult to decipher. Instead of showing these scupted images clearly as in the context of the museums where they are usually exhibited, Delogu allows them to emerge in a fleeting and hesitant manner from deep shadow, with contours barely defined.»

The statue is a three dimensional thing, subject within the space in which it is situated, to light and the possibility of being viewed from various different points of view. These variants make the statue available to reinterpretations and thus, an ever-changing object, contrary to the way it might initially appear — as something definitively fixed in time.

Photography makes these considerations explicit. The faces portrayed by Marco Delogu take on a different, subjective value even though they are not distorted, but simply captured by a sensitive eye that modifies them through lighting and composition. As Lidia Storoni Mazzolani observes in a text written to go with the portraits of Roman statues shown in this exhibition, «Delogu’s photographic eye seems gifted with psycological intuition. He has patiently observed beings who have been dead for millennia; their slight deformities, their melancholy, their awairness of approaching death. These ‘imaginary portraits’ are traced with extraordinary technical refinement, but above all with human compassion.»

The exhibition opens with this series of portraits of ancient Roman statues, one of the early projects of the photographer. This work immediately bears the characteristics that will become the distinguishing features of his work in successive projects. First of all the fact that he keeps returning to the face as a subject. Then, the use of lighting, that remodels the face, brings it forward and hides it, softens it and makes it harder. Finally, the portrait as series, the groupings, the bringing together of different faces joined by a common thread that is more or less significant. These elements will continue to characterise the future work of the photographer as he progresses from stone to the flesh of contemporary faces.

In the «Etruscan Portraits» this parallel between stone faces and living faces is made explicit by placing portraits of ancient Etruscan statues next to those of living people chosen among the inhabitatants of an area known for its Etruscan remains. As Geraldine A. Johnson writes «Most of the stone faces photographed by Marco Delogu have long ago lost their specific identity, but by placing living men and women next to these tufo and terracotta heads he helps to evoke, if not the names and personal histories of these people, at least the blood that once flowed through their veins and ‘the art of being happy’ («l’art d’être heureux») that the French writer Stendhal attributed to the ancient Etruscans. In his «Epistulae morales», Seneca suggested that » it is not a court full of famous images that makes someone noble.... but the the soul.(...) What Delogu depicts is not the fame, but the nobility of soul that is easily lost when we contemplate these objects in the bare context of a museum exhibit or on the patinated pages of an art book. By sinking them back into a mysterious darkness and reuniting them with the souls of men and women, Delogu ennobles both the sculpted faces and their living counterparts. Delogu’s photographs give life to ancient busts and dignity to modern faces.«

After the work on the Etruscan portraits Marco Delogu had not photographed statues for some time, when in 2002 he had the opportunity of photographing the Dancing Satyr, the ancient bronze sculpture which is believed to have been of Greek workmanship and which was found underwater in 1998 near Mazara del Vallo, in Sicily. Now for the first time Marco Delogu is exhibiting the photographs of the satyr as the statue begins a tour of Japan. After three days spent alone with the statue, Marco Delogu renewed his fascination with the features of ancient sculptures, and this gave rise to his latest work on the same theme; SPQR, a new interpretation of the faces of Roman statues from the Musei Capitolini (with the exception of the African boy which comes from the Archaeological Museum in Naples). This photographic work was shown in Rome in an exhibition in which the photographs of the sculptures were placed side by side with paintings by the painter Stefano di Stasio who had used the photographs to elaborate painted portraits where the figures were brought to life by placing them in a modern context. This exhibition features only one example of this pairing of photograph and painting in which a face dating back to more than two thousand years ago becomes the subject of two transpositions and reinterpretations in a contemporary context, thus taking on a new life. Emanuele Trevi wrote of this work: «For many years now Marco Delogu has been taking his «portraits of portraits» working through the collection of Greco-Roman statues in the Musei Capitolini.(...) There are a few rooms with the «important pieces», but there are also rooms that are much less visited and far more interesting, where the busts are lined up together in small spaces. It is like getting on a bus on an ordinary day; except that all the passengers are made of marble. Each one has his or her own individual face. Faced with this degree of variety, Marco Delogu chooses the features he wishes to capture. But he knows very well that all of those portraits have the same characteristic — in that they are all unique and unrepeatable. The result of the photograph is a violent transformation of dimensions: the volume of the statue is reduced to the surface of the photograph. But the essence is not lost in this transition. Like an agile creature, the physiognomy has jumped, entire, from the sculpture to the photograph.»

The work of Marco Delogu, whether of statues or persons is a continuous struggle to remember, to preserve memory, and sometimes to anticipate memory, Edoardo Albinati writes in his book ‘Maggio selvaggio’. " Marco showed me the pictures he took in jail. I know at least half of the inmates: in Marco’s photos they look older than they do in the flesh and as I see them from day to day. And yet perhaps the camera has captured something truly reflecting the significance of their existence, in a way that is detached, neutral and silvery, and which somehow represents them better than my daily contact with them can ever do...This is why these photos seem distant from the original subjects and yet their strange resemblance disturbs.

And the sense of this struggle is contained in Diego Mormorio’s presentation of the catalogue of the first group of Roman portraits: «Photography is man’s extreme rebellion against his mortality. It is the stone flung in the face of oblivion — and it is heavier and more accurate then the stone of antique portraits.

It is a luminous stone. «Now that we have been sculpted in light we will overcome the darkness of our disappearance», possessing our own photographic portrait might enocurage us to think, although it would be rational to acknowledge that sooner or later even the portrait will disappear. What is certain is that before disappearing our own stones will shine before many eyes and will probably encounter some for whom they shine with particular luminosity, as when the stones preserved in the Musei Capitolini encounered the gaze of Marco Delogu. Through careful observation he has placed stone upon stone, and has given a new and most beautiful form to the life of a few.»