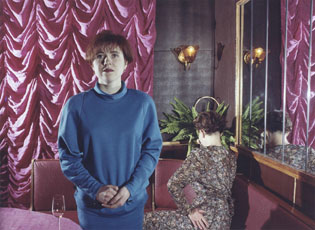

Photoprovocations

Sergey Chilikov From the series “Photoprovocations”, 1995 © Sergey Chilikov / Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Sergey Chilikov From the series “Photoprovocations”, 1995 © Sergey Chilikov / Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Sergey Chilikov From the series “Photoprovocations”, 1995 © Sergey Chilikov / Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Chongqing, 14.03.2017—31.03.2017

exhibition is over

Testbed 2

Chongqing, China

Share with friends

Exhibition in LianzhouFoto 2017

For the press

Sergei Chilikov is one of the most striking leaders of the new photography that appeared in the USSR in the 1970s.

This period known as Brezhnev’s Era of Stagnation is when Russian unofficial culture began to take shape in two important tendencies, Russian Romantic Conceptualism and Sots Art.

Sergei Chilikov, Boris Mikhailov, Nikolai Bakharev and Alexander Slyusarev were among the first to use photography as a working medium within the context of contemporary art.

They rejected the attempts in post-war years to formally reincarnate modernist traditions of the early 20th century. ‘Free’ reportage, heir to the traditions of European humanist photography, was left behind in the 1960s, a time of destabilisation and the Khrushchev Thaw. Brezhnev’s Stagnation tried to ‘tighten the screws’ all over again. The ideological machine formulated a new historical phenomenon, homo sovieticus. People deprived of the right to any individual manifestation of social life such as a career, the achievement of material prosperity or an individual style of life or thought became small screws in a decrepit ideological system. The Communist slogans that filled the social space to bursting point lost their triumphant power. In everyday life the oral genre of anecdotes that ironically outplayed Soviet ideology and articulated the absurd as a basic category of existence became increasingly prevalent.

Private life, which the Bolsheviks had abolished for more than half a century, moved to the forefront. In the wretched everyday life of Soviet man a narrow circle of friends made up this private content fitted into the five-seven metres of communal kitchens or their own corporeality, any display of this being prohibited in the social life of the period.

Precisely at this time Sergei Chilikov devised his own method — provocation by photo. The photographer with his camera acted like a director before whom his characters tried to become themselves, at least for a while. In its own right the camera directed at a human being became an emanation of the attention that the person was effectively deprived of in their monotonous everyday life severely restricted by the framework of the absurd Soviet system.

Sergei Chilikov presents his social performances primarily in the remote Russian provinces where life remained practically unchanged, even in the 1990s when both capitals, Moscow and St. Petersburg, had already experienced the perestroika and glasnost of Gorbachev’s rule and begun the ‘breakdown’ of the wild capitalism that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Chilikov builds his constructed compositions using a finely polished theory of detachment. The social performances he provokes are an extreme expression of the collective unconscious of homo sovieticus, and at the same time induce his participants to self-expression of what is ‘natural’ in man and was formerly deeply concealed behind artificial rules and norms.

As a result an electrifying tension arises between the statics of ‘unnatural’ poses and the dynamics in the inner state of these people. The miserable Soviet way of life in the Russian provinces is only a background. Sergei Chilikov manages to articulate the permanent rupture between the dream and surrounding reality in his work. With good reason his subjects are frequently women and children. A philosopher by education with three remarkable published works on philosophy, the photographer uses their faces as a projection screen for expression of the ‘Russian soul’ ‒ the central theme of classic Russian literature.

The photography of Sergei Chilikov is a unique version of the visualisation of a Chekhovian worldview, in which the absurd and the torment of the free spirit are realised within the closed contexts of banal everyday existence.

Olga Sviblova