Photographs and Diaries. 1929—1936

Exhibition shedule

-

9.12.2015—5.02.2016

Moscow

Multimedia Art Museum

-

3.02.2017—26.03.2017

Yekaterinburg

Yeltsin–Center

For the press

Mikhail Mikhailovich Prishvin (1873–1954), writer, author of works on nature and short stories about hunting, wrote a diary for half a century, from 1905 until his death. Not intended for publication, the journal contained reflections on what he saw and experienced, his interpretation of political events, and portrait sketches. In the years when his country endured troubled times, only those closest to the writer knew about the diary, which was kept far from prying eyes in the village of Dunino, where the writer had a house on the banks of the Moscow River.

Today the diary of М.М. Prishvin is widely acknowledged as one of the most remarkable 20th-century documents of Russian philosophical, literary and social thought. The writer’s wife Valeria Dmitrievna (1899–1979) was responsible for preserving his journal. After Mikhail Mikhailovich’s death she carried out the colossal task of deciphering all one hundred and twenty diary notebooks, copying, studying and then publishing them. Moreover, during her lifetime only a small part of the journal appeared in print, a few grains ‘sifted’ through the ‘fine sieve’ of Soviet censorship. The remainder were kept in a metal safe acquired specially for this purpose, in the hope that times would change for the better.

His photographic work is equally interesting. Prishvin first took up photography during a trip to the Russian North in 1906 and illustrated his first book, In the Land of Unfrightened Birds (1906), published after the journey, with his own pictures. Later he recalled that after browsing through these photographs the publisher enquired if painting was his primary occupation. The camera he used then came to hand by chance, thanks to his encounter with a fellow traveller during the expedition. Only in 1925 did Prishvin finally buy a camera himself and master its finer points, but from that moment photography, the phenomenon of 20th century culture, constantly accompanied his creative work and ranked in importance with his notebook and diary. The writer became enthralled by photography and from that day forward took his camera wherever he went.

‘2 September 1930. I’m so captivated by the hunt with my camera that I only sleep in the expectation that very soon another bright morning will dawn.’

Photography became an organic extension of Prishvin’s literary activity — gifted by photographic powers of observation, he keenly felt the process of visualisation in contemporary culture and understood the hidden opportunities in interaction between fine art and the art of the written word. The writer seems to have needed more than purely literary images and snapped away relentlessly, dreaming that one day he might publish his own photographic album.

‘26 September 1929. So now I have a camera. I use it to depict reality, in the same sense that I myself, an artist of the written word, exist to take evidence. To my imperfect literary art I add photographic inventiveness in order to create, little by little, the most versatile art form for depicting the present moment in life.’

The writer tried not to use photography as his starting point, emphasizing that he brought ‘photographs to his literary works not as a reporter’, not to illustrate text, but constructing a parallel lexical and visual perspective, and in this way achieving the breakthrough to new meaning. Photography corresponded to everything inherent in Prishvin’s artistic awareness: attention paid to personality, reality, nuances, particularities and facts; photography materialised his attempt to reflect the period in documentary fashion, by capturing elusive detail.

‘Undated. Capturing the fleeting moments of life... this craft in the hands of an artist signifies attention to life... photography is explained by the artist’s uncontrollable striving for truth... is this art? I don’t know, but it should at least resemble a fact.’

Prishvin’s photographic style is distinctive for its restraint and simplicity, although this did not annul or simplify his enthusiastic procedure for mastery of the photographic language or the search for new camera techniques. He worked in a way atypical of the professional journalist, yet at the same time unlike any amateur photographer — he sees the world through the eyes of an artist.

‘Undated. Of course a real photographer would take better shots than me, but it would never occur to the true specialist to look at the things I photograph: he wouldn’t see them.’

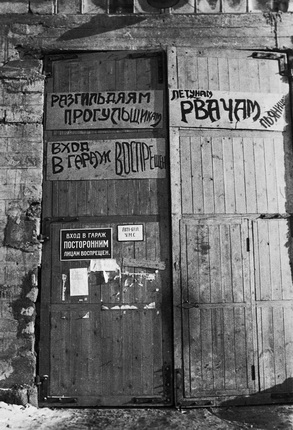

His photographic material lifts the veil of silence from reality and reveals a truth it is impossible to contradict or conceal. In the portraits the complexity of the world is revealed by facial expression, a tilt of the head, a gaze, a gesture or items of clothing. The industrial landscape features technical objects, engineering constructions, machines, steam engines, handcars, automobiles — the zeal of the new age expressed in geometrical metal structures, in the scale of the timber rafting, and the canal construction contends with the image of the man implementing construction of a new life. In the landscape shots the pursuit of light and shade, the assertive foreground and the panorama or view from above broadens the customary perception of green nature: droplets, a spider’s web, a sunbeam or buds become the subject of the shot; beside the photographer on the roof of the House of Writers on Lavrushkinsky Lane is his beloved dog Zhizel [Giselle], Zhulka for short, gazing attentively at the Kremlin and rows of Moscow buildings with multiple windows.

The destruction of the bells at Trinity-Sergius Lavra was a very special theme. A tin tea caddy has been preserved in the writer’s photo archive with a white paper label in his handwriting glued to the lid: When they smashed the bells. Prishvin kept these films in the tea caddy separate from the rest of his archive, cut into individual frames.

‘5 September 1929. The value of the photograph is that it precisely conveys an image of the world, and as a result we are convinced it exists in its own right, independent of our perception. I want to make use of this particularity of the camera and show my vision of the real world through photography.’

For Prishvin the sequence of this examination of the world in the form ‘journey — photograph — diary notebook — finished work’ is practically universal. A series of photographs creates a visual image of the world that allows for the description, comprehension and interplay with notes of the Journal.

‘Undated. 1942. If my shots survive until people begin to live ‘for themselves’ my photos will be published, and everyone will be surprised how much joy and love for life this artist kept in his heart.’

Photography provided a remarkable opportunity to reveal in a natural landscape the hidden image concealed within — and this became the writer’s creative work with a visible image, an unlimited expansion and complication of the world.

‘Undated. The image develops on the film and often it seems your eyes are opened wider and wider... Extraordinary! Something very different appears, and differently from the way it was photographed. Where did that come from? If I didn’t notice when I was taking the shot, that means it existed in its own right in the ‘nature of things’... then it seems that if you can lift the veil, people will see there is beauty on earth, and meaning within it.

Undated. I devoted the morning to photographing the frost. Found what was probably an old, abandoned spider’s web, thickly encrusted with ice. Photographed tiny whitened stars of moss, now more like crystals. Using a stump as a black background, I took shots of leaves framed by a lacework of frost. Tried to photograph glistening frozen branches against the sunlight. When things go wrong, I turn to photography.’

Yana Grishina