Robert Mapplethorpe and the Classical Tradition: Photographs and Mannerist Prints

The Graces. Jacob Matham after Hendrick Goltzius. 16th century. State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Diana in the Clouds. Jacob Matham after Cornlis Cornelisz. Van Haarlem 16th century. State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

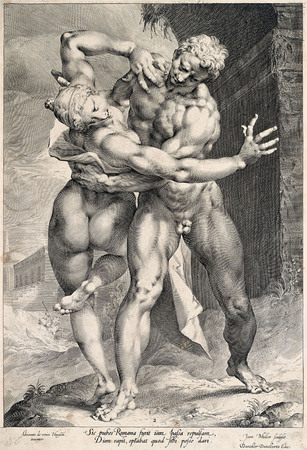

A Roman Abducting a Sabine Woman, from the Rape of the Sabine Women. Jan Harmensz. Muller after waxworks by Adriaen de Vries. 16th Century. State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

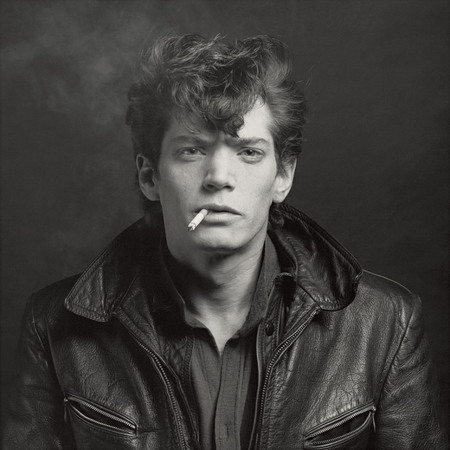

Robert Mapplethorpe. Self-portrait. 1980. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe. Self-portrait. 1980. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

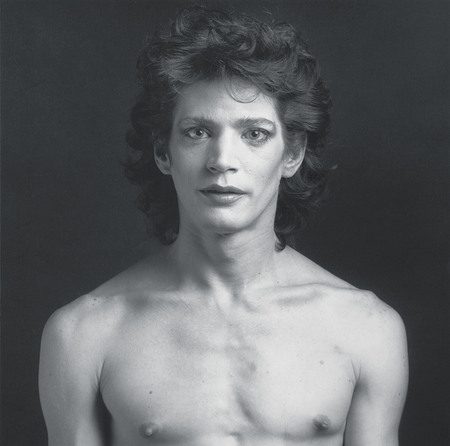

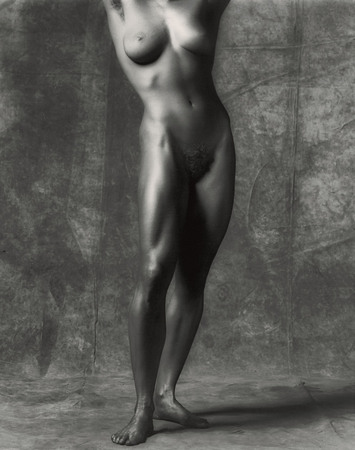

Robert Mapplethorpe. Lisa Lyon. 1981. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

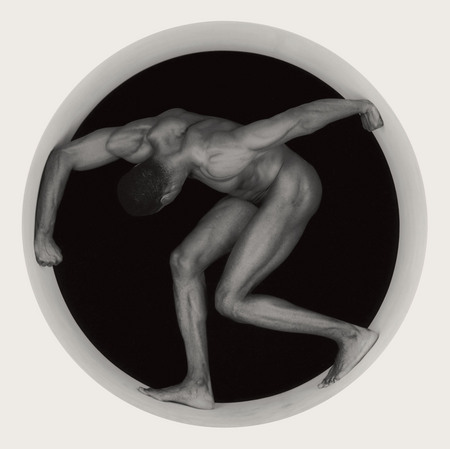

Robert Mapplethorpe. Thomas. 1987. Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

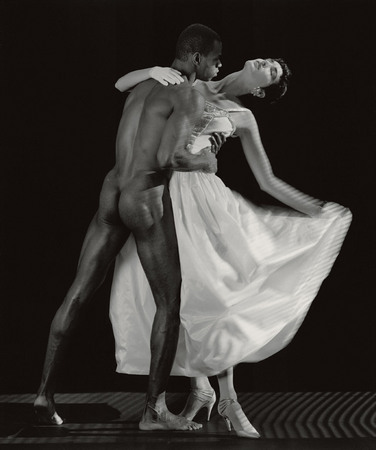

Robert Mapplethorpe. Thomas and Dovanna. 1986. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

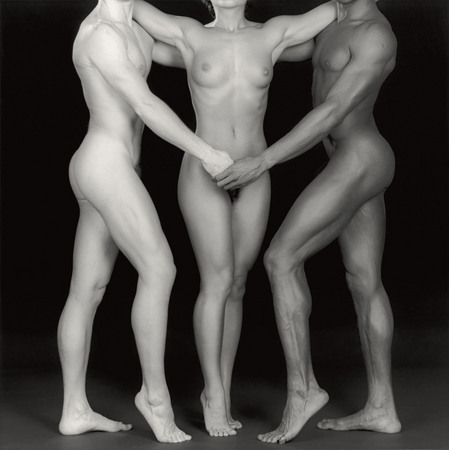

Robert Mapplethorpe. Ken, Lydia, and Tyler. 1985. Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe. Antinous. 1987. Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Moscow, 22.01.2005—6.03.2005

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Organized by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, and the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

Curators: Germano Celant and Arkady Ippolitov, with Karole Vail

For the press

This exhibition explores the dialogue between the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe

Deeply rooted in Italian art, Mannerism was an international movement that arose after the death of Raphael in 1520. Mannerist printmaking spread to France and the Netherlands, as well as Germany and Prague. Referred to as the stylish style, Mannerism is characterized by emotional and narrative elements that shift from the balance of harmony and equilibrium articulated by the art of the High Renaissance. In order to emphasize torsos and limbs, Mannerist artists often violated classical canons of perfect proportions. Figures were not only nude, but elongated and elaborate in a near vertiginous fashion, indicating the artists’ mastery of anatomy. In some cases the figures were nearly grotesque in their depiction of exaggerated musculature, as exemplified particularly with the work of Goltzius. Likewise, the physical distortions underscored the drama and cruelty of the narrative, though grace and wit were important features of the Mannerist aesthetic, as reflected in their choice of mythological and allegorical subjects.

The electric and emotive potency of love and Eros, which informs many of the Mannerist works in the exhibition, is expressed as well in the work of Robert Mapplethorpe, whose sometimes shocking photographs reveal compelling strength and a nervous energy. One of the most legendary and recognized photographers of the twentieth century, Mapplethorpe tragically died at the young age of forty-two. His photographs have appeared in numerous solo and group exhibitions and hang in major collections worldwide. Mapplethorpe was born in New York where he studied painting and sculpture at the Pratt Institute; he first made art that integrated photographic images borrowed from other sources, including pages torn from magazines and books. He also made erotic collages and then gravitated toward photography, at first with a Polaroid camera. His elegant and sometimes provoking nudes, the black-and-white portraits, gorgeous flowers and still lifes, as well as the powerful, often surprisingly tender images of sexual sadomasochism have had an undeniable impact on the art world and have been the subject of serious critical attention internationally.

In the 1970s, Mapplethorpe witnessed two simultaneous but distinct events: the rise of the market of photography as a fine art, and the explosion of punk and gay cultures. Using a large-format press camera, he began taking photographs of a wide circle of friends and acquaintances, including artists, composers, socialites, pornographic film stars, and members of the urban underground. At the time some of these photographs were considered scandalous for their content but were recognized as exquisite in their technical mastery. Later, Mapplethorpe’s photographs shifted toward the refinement of subject matter and an emphasis on classical formal beauty. He concentrated on statuesque male and female nudes, delicate flowers, and formal portraits. Not considering himself a photographer, Mapplethorpe continuously challenged the definition of photography by introducing new techniques and formats to his oeuvre: color Polaroids, photogravure, platinum prints on paper and linen, Cibachromes, and dye-transfer color prints, as well as black-and-white gelatin-silver prints.

Passionate about the human body in his creative quest, Mapplethorpe described photography as «the perfect way to make a sculpture.» He looked for perfection in form with every subject he tackled, and his photographs, ripe with sculptural tension, are imbued with an erotic ambiguity. Furthermore, the classical ideal was not only a poetic inspiration for him but also an ethical model that he sought to emulate throughout his short life. He combined harmonious sculptural excellence with photographic absoluteness, striving to mirror art in life and art in photography. In this way, he was able to express radical themes in typical historical terms. Partaking of classical naturalism, his compositions are meticulously thought out and reflect a highly detailed perusal of figural gestures, from the perfection of Michelangelo to the elegance of 18th- and 19th-century artists. The vital anatomical forms of his portraits, such as the bodybuilder Lisa Lyons and the statuesque dancer Derrick Cross, find their roots in antiquity, and here are mirrored in the highly expressive 16th-century prints of Muller’s The Rape of the Sabine Women and Matham’s dynamic Apollo in the Clouds. The marble scultpure in the exhibition highlights the dialogue of Mapplethorpe’s photographs and the Mannerist prints with classical antiquity, further illustrating their compelling relationship and a broader understanding of the history of art.