Eye to Eye. Histories of stereo photography

Tomashkevich I. R. On the rock pillars near Krasnoyarsk. Krasnoyarsk region. 1890s. Silver gelatin print. MAMM collection

Zakhar Vinogradov. 'Life and Nature of Russia. Volga and Privolzhye' series. Trees inundated by spring flooding of the Volga. Lower reaches. 1913. Silver gelatin print. MAMM collection

Zakhar Vinogradov. 'Life and Nature of Russia. Volga and Privolzhye' series. Sandbars below Vasilsursk. 1913. Silver gelatin print. MAMM collection

Zakhar Vinogradov. 'Life and Nature of Russia. Volga and Privolzhye' series. Scarecrow in a melon field. Saratov province. 1913. Silver gelatin print. MAMM collection

Unknown author. Publishers Underwood & Underwood. 'A golden autumn day softly vanishes in stillness and sunbeams'. Japan. 1896. Albumen print. MAMM collection

Unknown author. View of a fountain. Russia. Late 19th – early 20th century. Albumen print. MAMM collection

Unknown author. Publishers Joint-Stock Company Aristophot, Taucha. Grove. 'Caucasus' series. Germany, late 19th – early 20th century. Silver gelatin print. MAMM collection

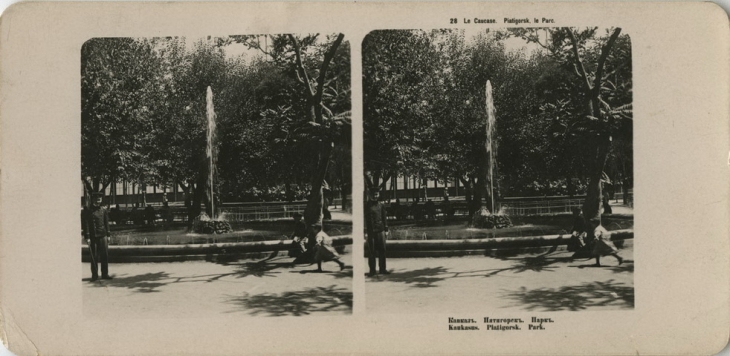

Unknown author. Neue Photographische Gesellschaft A.-G., Steglitz-Berlin. Caucasus. Pyatigorsk. Park. 1906. Silver gelatin print. MAMM collection

Unknown author. Tableau vivant. Girls by a screen. Late 19th – early 20th century. Tinted albumen print. MAMM collection

Unknown author. Scene from the play 'Uncle's Dream'. Late 19th – early 20th century. Tinted albumen print. MAMM collection

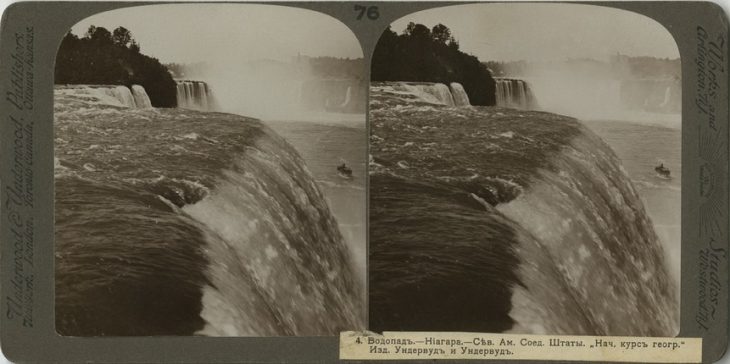

Unknown author. Publishers Underwood & Underwood. 'Elementary Geography Course' series. Niagara Falls, USA. 1900s. Albumen print. MAMM collection

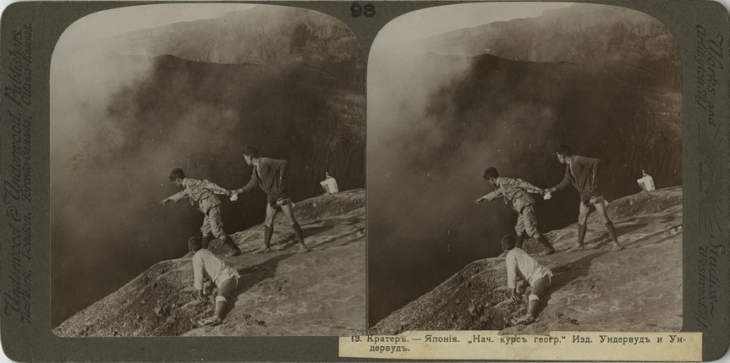

Unknown author. Publishers Underwood & Underwood. 'Elementary Geography Course' series. View of Mount Aso crater through sulphurous vapour. Japan. 1900s. Albumen print. MAMM collection

Moscow, 27.06.2013—8.09.2013

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Curator: Olga Annanurova

For the press

Today the three-dimensional image is a part of everyday life: we visit 3-D cinemas, buy magazines with 3-D illustrations and use such methods for printing and web design, regarding stereo pictures as a more or less modern technological achievement. However, its history covers almost two centuries, and the effect of the three-dimensional picture has enchanted viewers since the 1830s. The ‘Eye To Eye’ exhibition devised by the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow with the participation of the Polytechnical Museum presents various episodes from the story of stereo photography, inviting the modern viewer to independently recreate the order of events and see that one of the most popular leisure activities of the 19th century can also be an object of interest to the sophisticated audience.

Despite changes in technologies, the basic principal for creating a three-dimensional photograph remains unchanged: two shots of the same subject must be taken (corresponding to the vision of the left and right eye), which then fuse into one stereo picture when viewed together. Viewing methods have changed more radically: screens and special glasses now facilitate collective viewing, while viewers peering into a stereoscope were left one-to-one with the image.

Due to its extraordinary mass appeal, the stereo photograph never aspired to the status of an artwork. One of the particularities of stereoscopic views is that the author usually remained anonymous. The key role here belongs not to the photographer, but to the company issuing stereographic cards: Underwood & Underwood in the USA, Great Britain, Japan and Canada; the joint-stock company Granberg in Sweden; the Svyet stereographic publisher in Russia, etc. The processing and production in large editions of stereoscopic views and special compilations, either sold separately or in a set with stereoscope included, became a profitable business venture.

As a commercially successful enterprise, at first sight early stereo photography served two diametrically opposed goals. On the one hand it was included in the sphere of scientific knowledge: medicine, geography, astronomy and other sciences could now use a new type of image as visual aid. Stereo photography appeared to intensify reality, and each object became accessible to the ‘probing’ eye of the beholder. Everything that had previously seemed abstract (for example the correspondence between phases of the moon, the ebb and flow of tides) acquired a material form that could be observed in the stereoscope. Moreover, stereoscopic images taken in various parts of the world (Japan, China, Canada, etc.) that in the mid- and late 19th century remained an abstraction for most Europeans, as much as lunar phases and biological processes, proved especially popular. Sets of stereo photographs from exotic lands were a substitute for exhausting real-life journeys and the viewer could obtain a comprehensive impression not only of the natural world and landscapes, but also of the people inhabiting, for example, the island of Hokkaido. The three-dimensional image seemed to make up for the lack of mobility in the life of 19th-century man, who froze in expectation of revolutionary change, the attainability and accessibility of the world outside. Stereo photography became an indispensable tool in the effort to describe and catalogue the environment, an aspiration of many scientists in the 19th century. Characteristic in this respect is the series of stereo photographs by Russian photographer Zakhar Vinogradov, who went on numerous expeditions throughout the Russian Empire and returned with highly detailed photographic records, most taken with a stereo camera.

The stereoscope also became an essential feature in urban living rooms, as a means of entertainment. The viewing and creation of stereo photographs became a respectable domestic leisure activity, when family members and friends could gather together for a journey to the other side of the globe, or take part in creating so-called ‘tableaux vivants’, staged scenes depicting a popular episode from literature or history that were recorded on a domestic stereo camera and then viewed, to the delight of all participants. However, stereo photography was not always a means of exclusively respectable entertainment: in the mid-19th century erotic and even pornographic cards were widely circulated. Due to the same ‘naturalism’ of the image, viewing such photographs provided sensory pleasures of a very different kind.

Stereo photography had achieved mass popularity by the early 20th century and gradually made way for new types of representation. Although losing precedence, it left viewers with an experience peculiar to our perception of three-dimensional images. Today the illusion of easy transit to another world, both terrifying and compelling, is intriguing audiences yet again. In turn all the effects that in one way or another originated in stereo photography — volume, the layering of images, the length of viewing and change in the focus of attention — have been used as techniques by contemporary artists for some time. The stereoscopic image, initially far removed from aesthetic pretensions, has been appropriated as a mode of art and thereby acquired new importance.