Studio 54

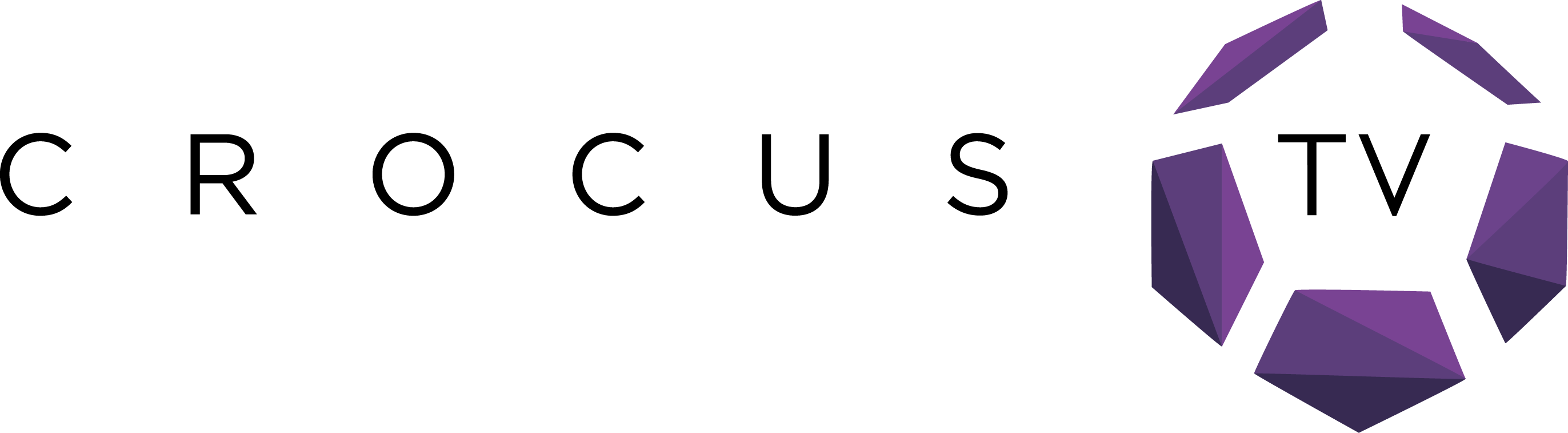

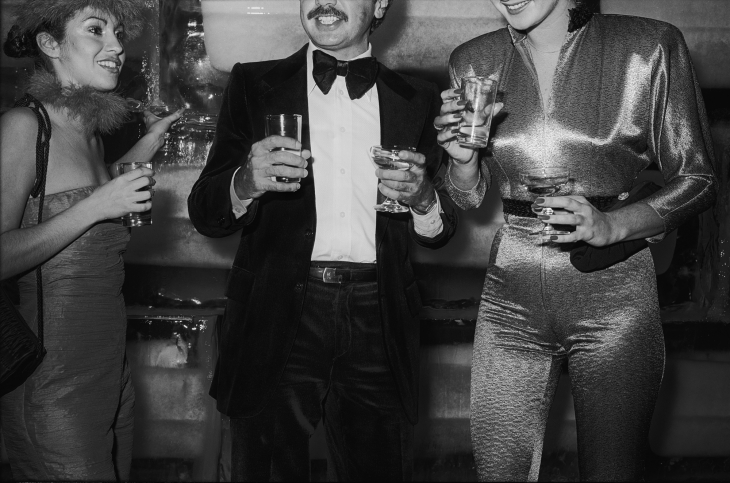

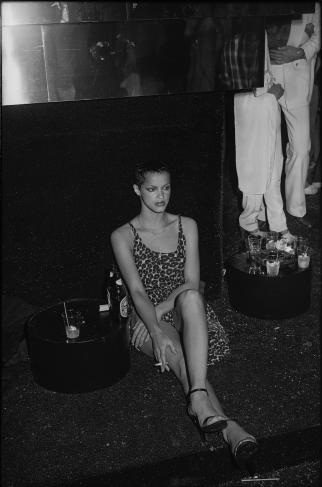

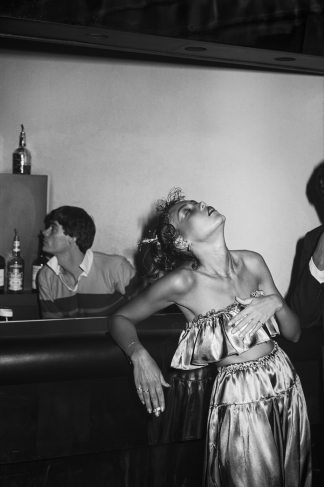

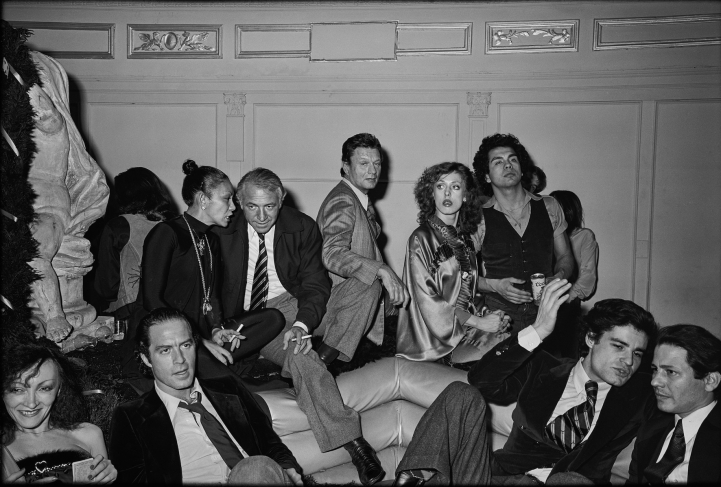

Tod Papageorge Untitled. 1978 From the series ‘Studio 54’. New York, 1978—1980 Gelatin silver print © Tod Papageorge, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Tod Papageorge Untitled. 1978 From the series ‘Studio 54’. New York, 1978—1980 Gelatin silver print © Tod Papageorge, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Tod Papageorge Untitled. 1978 From the series ‘Studio 54’. New York, 1978—1980 Gelatin silver print © Tod Papageorge, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Tod Papageorge Untitled. 1978 From the series ‘Studio 54’. New York, 1978—1980 Gelatin silver print © Tod Papageorge, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Tod Papageorge Untitled. 1979 From the series ‘Studio 54’. New York, 1978—1980 Gelatin silver print © Tod Papageorge, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Tod Papageorge Untitled. 1978 From the series ‘Studio 54’. New York, 1978—1980 Gelatin silver print © Tod Papageorge, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Tod Papageorge Untitled. 1979 From the series ‘Studio 54’. New York, 1978—1980 Gelatin silver print © Tod Papageorge, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Moscow, 21.02.2020—30.07.2020

exhibition is over

Share with friends

As part of the Photobiennale 2020

For the press

Tod Papageorge

«Studio 54»

As part of the ‘Photobiennale-2020’ the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow presents a project created at the legendary club Studio 54 from 1978 to the 1980 by Tod Papageorge, one of the most influential American photographers.

This illustrious New York nightclub at the intersection of Manhattan’s West 54th Street and Broadway opened in 1977 in a former theatre, while preserving the previous atmosphere and interiors. Due to the new owners’ ability to organise crazy parties that offered everything sophisticated New York bohemians could imagine, and the imposition of strict face control, Studio 54 instantly became the place to be and be seen. Guest lists included Andy Warhol, Liza Minnelli, Elizabeth Taylor, Mick Jagger, Diana Ross, Michael Jackson, Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and many others. Visitors ‘from the street’ could also access the club, but the last word always remained with the proprietors, who maintained the image of an élite venue of world renown.

Inspired by Brassaï’s 1930s pictures of Parisian nightlife exhibited at МоМА, Tod Papageorge resolved to capture the glamorous, decadent atmosphere of New York by night, and Studio 54 was its very quintessence. Papageorge made his first appearance at the club on 1 January 1978. The New Year celebrations lasted until dawn. All the shots were taken with a heavy medium-format 6 × 9 camera. As Tod Papageorge recalls, ‘I was uninterested in using my smaller 35mm Leicas for this project, not when I hoped to capture something of the actuality of flesh and sweat and desire that I’d recognised in the Hungarian photographer’s work, and imagined that the Fujica (which produced negatives four times the size of the Leica) might help me also achieve. My hope was that, if I could do it, my pictures would own the detail and tonal fullness characteristic of those larger negatives, while being charged by the sense of unfurling energy I’d always tried to tap in my work with the Leica and associated with the small-camera photography I admired.’

Fifty-four pictures from the series were taken in 1978 (by chance the number coincides with the name of the club). When he began work Tod Papageorge tried not to get too carried away — he could only take eight shots on one reel before being obliged to stop and change the film. This limitation demanded immense concentration that was extremely difficult to sustain, given the intense (visual, sensual and sound) impact of the Studio 54 setting. The photographer roamed the club looking for scenes to photograph, and before the bulky camera was launched into action he mentally aimed the viewfinder at interesting characters or piquant scenes. As soon as a story worthy of being told entered the frame’s imaginary space, Tod Papageorge would lift the camera into view and take a shot.

‘…Here are the pictures that came out of those nights. Obviously, they’re more compelling than anything I could say about my method of making them or the cameras I used to do it... They were always meant to speak for themselves, with a persuasiveness distinct from the fact-telling of journalism or the occluded eloquence of “old” photographs. Let’s call it poetic eloquence instead, an expressiveness shaped by the photographer’s sense of form… acting on the ether that is his or her intuition reading the world,’ says the photographer.

________________________________________

Tod Papageorge was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in 1940, and started taking photographs while still studying at the university. After seeing the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson he decided to become a photographer. In 1965 he spent ten months shooting in Spain and Paris, then returned to the USA and moved to New York, where he met Robert Frank and was invited by Garry Winogrand to participate in a workshop that Winogrand was about to initiate at his apartment on Sunday evenings.

This was a heady moment for photographers in New York. Frank’s celebrated book ‘The Americans’ was published in 1958, and the appointment in 1962 of John Szarkowski as Director of the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art formed the backdrop for what turned out to be a critical transition point in the evolution of American photography in general, and street photography in particular. Tod Papageorge found himself in the middle of it.

In 1977 he curated ‘Public Relations’, an exhibition of Garry Winogrand’s photographs at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and four years later the exhibition ‘Walker Evans and Robert Frank: An Essay on Influence’ for the Yale University Art Gallery.

In the late 70s Papageorge became a Professor of Photography and Director of Graduate Studies in Photography at the Yale University School of Art.

In addition to his two Guggenheim Fellowships, Tod Papageorge has received two National Endowment for the Arts grant.

His photographs are represented in important state collections including the Museum of Modern Art (New York, USA), the Art Institute of Chicago (USA), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (USA) and the National Library of France in Paris.