Polonius

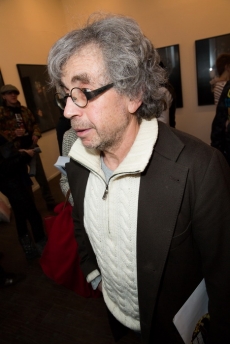

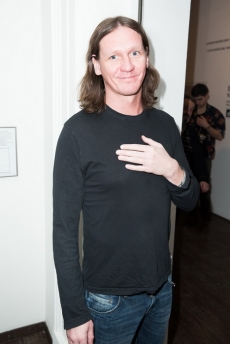

Vlad Monroe. Polonius. 2012. Photographer: Grigoryi Poliakovskiy. Digital print

Vlad Monroe. Polonius. 2012. Photographer: Grigoryi Poliakovskiy. Digital print

Vlad Monroe. Polonius. 2012. Photographer: Grigoryi Poliakovskiy. Digital print

Vlad Monroe. Polonius. 2012. Photographer: Grigoryi Poliakovskiy. Digital print

Moscow, 6.03.2013—5.04.2013

exhibition is over

Moscow Museum of Modern Art

17 Ermolaevsky lane (

www.mmoma.ru

Share with friends

Polonius, an exhibition of Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, a famous artist, produced in cooperation with photographer Grigory Polyakovsky, echoes a recent Polytheater premiere of the same name where Monroe played the part of Polonius.

For the press

‘Hamlet’ is undoubtedly one of the most universal plays in human history. Every actor dreams of playing Hamlet. Why? That is the question. The complex structure of the drama leads us to conclude that Hamlet should be played by a NON-ACTOR, since Hamlet comes from another world, neither that of the royal court (as in the play), nor that of the theatre (as in life). The conflict in the play and the difficulty of any staging lie in Hamlet’s otherness. Hamlet is like a breath of air from another world (whether this is a new or distorted world is another question). We decided to actively resolve this contradiction by casting a non-actor in the role of Hamlet (neither a man nor a professional player). So what to do with the great monologues? Give them to someone else. To the tragic and poignant Polonius, a role that has clearly been undervalued by many directors. This decision prompted us to rename the play. The brilliant, flamboyant Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe (‘wretched, rash, intruding fool’) has produced a hyper-theatricalisation of Shakespeare’s splendid stanzas. Which emphasizes the otherness, aloofness and self-absorption of Hamlet, a role we have given to Alison (Elena Kamaeva). Our approach to the costumes and musical accompaniment is equally extraordinary. A detailed treatment of the play’s central themes has allowed us to relinquish many incidental and vague schema that were necessary in Shakespeare’s time but confusing for our contemporaries (e.g. the foreign policy conflict with Fortinbras). The figure of Hamlet’s father, which arouses so many difficulties whenever the play is staged, has been placed inside the unfortunate prince’s own head, in acousmatic form (a voice from an unknown source)’

Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe’s exhibition ‘Polonius’, prepared in collaboration with the photographer Grigory Polyakovsky, was created using themes from the play of the same name recently premiered at Moscow’s Politeatr, where Monroe simultaneously played Polonius and the Gravedigger. The creators define the genre of this production as a fashion show in which designer and couturier Katya Filippova becomes the costume and set designer. Taking Shakespeare’s Hamlet as their main subject, the authors of the play reassigned as the lead character the tragic figure of Polonius (played by Monroe), who accordingly voices all of Hamlet’s monologues. In this drama Polonius becomes a key character answerable for the reality that is heard, seen and felt by the spectator, since Hamlet is practically transformed into an ephemeral substance: the authors of the production accentuate to the utmost degree the idea of estrangement and exclusion from the world. Nonetheless, the photo project on the theme of ‘Polonius’ maintains a certain distance from the stage show, since for Monroe this is more like an ideal and long-awaited pretext to fully develop and realise a theatre situation in his own terms, and thereby discover the nature of theatricality in general and in his own particular case. Even if we suppose that a treatment of Hamlet is entirely commensurate with Vlad’s customary search for an archetypal, ‘basic instinct’ image (from Marilyn Monroe, ‘best-loved of all women’ or the classic ‘New Year calendar from the lives of famous people’ to Lyubov Orlova), in the ‘Polonius’ photo project Monroe is from the outset an actor, performing on the stage in a theatre production, submitting to the will of the director and interacting with partners. As before, in these works we clearly experience the skilful debasement of everything lofty and indisputable to a level of inevitable absurdity and shameless mockery. But we are presented with more than a travesty of the classic dramatic plot and canon — entirely in accord with the concept devised by the play’s creators, Monroe touches on sore points of the present-day political situation, acting out on another level his own ‘Death of Gonzago’. In the new series another important factor appears: Monroe’s genuine fascination with the stage and professional acting; he gives a brilliant performance of the mises-en- scène of Shakespeare’s classic work, appearing in the image of Gertrude, Claudius, Ophelia, etc. At the same time he pays considerable attention to pose and gesticulation — sooner or later you have the feeling that this is an exhibition about hands and their virtuoso dance-like plasticity. It seems that Monroe revels in the possibilities of his ‘histrionic’ body, providing the audience with an opportunity for sheer contemplation, for pleasure at the theatrical situation.