Vsevolod Tarasevich. The retrospective

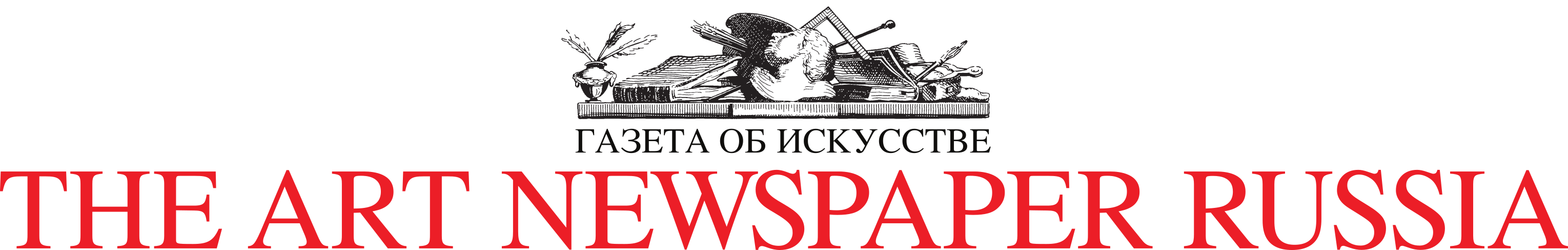

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Duel. From the series "Moscow University". 1964. Collection of MAMM

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Kiss. 1966. Collection of MAMM

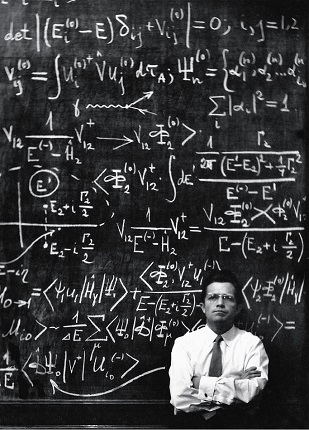

Vsevolod Tarasevich. The atom is inexhaustible. From the series "Institute of High Energy Physics in Protvino". Moscow Region, Protvino, 1969-1974. Collection of MAMM.

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Preparing for the crossing of the Neva. Leningrad Region, 1941

Vsevolod Tarasevich. At the parking lot of the children's taxi "Karapuz". Arkhangelsk, the 1960s. Collection of MAMM

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Samotlor. From the series "Reporting from the front edge." Tyumenskaya obl., 1968. Collection of MAMM

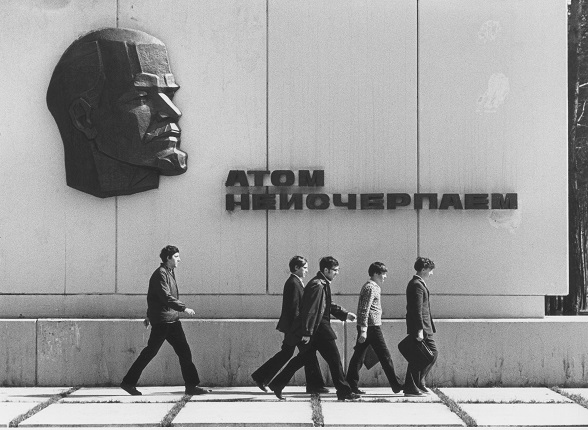

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Untitled. From the series "Nevsky Prospekt". Leningrad, 1965. Collection of the MAMM

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Untitled. From the series "Nevsky Prospekt". Leningrad, 1965. Collection of the MAMM

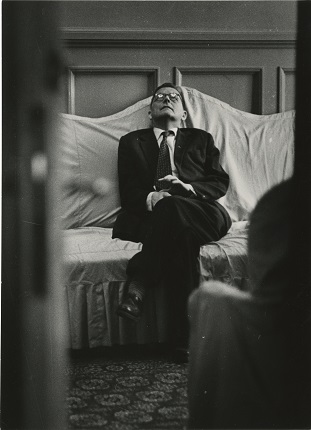

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Dmitry Shostakovich. The Twelfth Symphony. 1961. Collection of MAMM

Moscow, 9.02.2018—1.04.2018

exhibition is over

Share with friends

As part of the Classics of Russian Photography programme and Photobiennale 2018

For the press

MOSCOW GOVERNMENT, MOSCOW CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE, MULTIMEDIA ART MUSEUM, MOSCOW / MOSCOW HOUSE OF PHOTOGRAPHY MUSEUM

AS PART OF XII INTERNATIONAL MONTH OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN MOSCOW ‘PHOTOBIENNALE 2018’

MULTIMEDIA ART MUSEUM, MOSCOW PRESENTS THE EXHIBITION: VSEVOLOD TARASEVICH. RETROSPECTIVE

The Vsevolod Tarasevich Retrospective showcases the work of a classic master of Russian photography who could easily be ranked with great initiators of humanist photography such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau and Marc Riboud. This is an event MAMM has been preparing for over the last 18 years.

The Tarasevich Fund acquired by our museum in 2000 includes more than 18 thousand negatives and authorial prints. For almost 20 years the museum’s specialists have been documenting and attributing this fund. In 2013 the museum presented the ‘Time Formula’ exhibition of Vsevolod Tarasevich’s work, in 2014 ‘Vsevolod Tarasevich. Episode 2. Leningrad’ and in 2015 ‘Norilsk’. The retrospective of this remarkable photographer provides an opportunity to appreciate the versatility of Vsevolod Tarasevich’s talent, demonstrating the evolution of his style over more than 40 years — from the first wartime shots of the 1940s to the pre-perestroika reportages of the mid-1980s. About half of the more than 300 photographs featured in the exhibition are shown for the first time.

Vsevolod Tarasevich (1919—1998) began taking photographs during the war and worked as military photo correspondent from 1941 to 1945. Only a few negatives have been preserved from that period. Tarasevich’s most famous pictures from the war years were taken at the Siege of Leningrad and on battlefields outside the city. ‘During the war many things could not be shown... But I went on taking photographs. It was my obligation and duty,’ the photographer recalled. Tarasevich’s wartime images provide some of the most striking records of the worst tragedy the 20th century ever witnessed. The war years laid the foundations for the style and humanist outlook that would later make Tarasevich the most important exponent of the subsequent Thaw in the 1960s.

After the war Tarasevich worked at the main Soviet information agency, the Novosti Press Agency (APN), and his photographs were published in the magazines Sovyetsky Soyuz, Ogonyok, Rabotnitsa and Soviet Life. In the 1950s he paid tribute to staged photography and was among the first to master colour film. This corresponded to the spirit of the times, since in the 1950s staged composition dominated in all leading Soviet illustrated publications. Cheerful collective farmers, laughing Pioneers, Communist Party organisers conversing intently with the conquerors of virgin lands — these characters in Tarasevich’s photographs are recognisable and repeated in abundance on the pages of Ogonyok through those years. Yet at the same time Tarasevich sought his own individual path. From the photographs taken in Sverdlovsk in 1958 it is clear how he hones his mastery of composition and geometric alignment of the frame, reprocessing the legacy of constructivism. Another important feature of his images from the 1950s is the capacity to capture direct human emotion in the lens. The crowd in Tarasevich’s photographs at an exhibition of scientific and technical achievements in Kharkov in 1957 stares at the model of a sputnik and at a washing machine on display with the same genuine perplexity and admiration. His ability to photograph an event as it evolved, to empathise with the subjects, and his remarkable talent for conveying the atmosphere of what happened were soon in demand in the period of the Thaw, an era of sincerity, of emancipation and intolerance of staged falsity.

The late 1950s to mid-1970s marked the epoch of ‘physicists and lyricists’, a time when the significance of education and science were re-evaluated in the USSR. In the brief period from 1958 to 1978 Novel Prizes were awarded to Soviet scientists on four occasions. Tarasevich took photographs of Moscow University, Novosibirsk Akademgorodok, the Institute of High Energy Physics in Protvino, the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Biological Physics in Pushchino and the RAS Scientific Centre in Chernogolovka… The students and scientists of these educational and scientific clusters were heroes of their time, inspired by a romantic belief in the infinite power of free human thought. Tarasevich’s reportages were the best visual expression of the epoch, and he retained this atmosphere in his work to the very end of his life.

In the 1960s to 1980s Vsevolod Tarasevich travelled widely in the USSR and brought back reportages from Naryan-Mar, Magnitogorsk, Samotlor and Tolyatti, visiting all the far-flung corners of this vast country. One of his best photo reports is devoted to Norilsk, to which Tarasevich often returned in the 1960s to 1970s. Until 1953 this city had the status of ‘special settlement’: the Norilsk Combine built by prisoners of the Norilsk Corrective Labour Camp was one of the largest projects of Stalinist industrialisation. Tarasevich’s Norilsk depicts the epoch after the 20th Congress of the CPSU (1956), the congress of de-Stalinisation. Naturally the harsh climate, squalls and snowstorms, constant conditions for Norilsk citizens, are caught in the photographer’s lens, as well as the everyday lives of workers at the metallurgical combine or the leisure time of Norilsk people. Tarasevich’s Norilsk photographs breathe freedom: dances in the café, facial expressions, the style of dress and behaviour of the subjects are the same as in shots taken in the 1960s in Leningrad. Every one of these works is a hymn to the humanist photography that in those years captured not only the USSR, but also Europe and America.

Vsevolod Tarasevich’s works are consonant with the aesthetics of 1960s cinema. The internal dynamics inherent in every frame involuntarily unfolds in the viewer’s perception like a movie story. It is actually impossible to scan the photographer’s images in a quick and superficial manner. They are hypnotic. Acquaintance with Tarasevich’s works provides the opportunity not just to learn new facts about our history, but also to feel the joy of a living experience of time.