H-Hour

Grisha Bruskin. "On the Edge". From "H-hour" series. A part of the installation. 2012. Courtesy of author

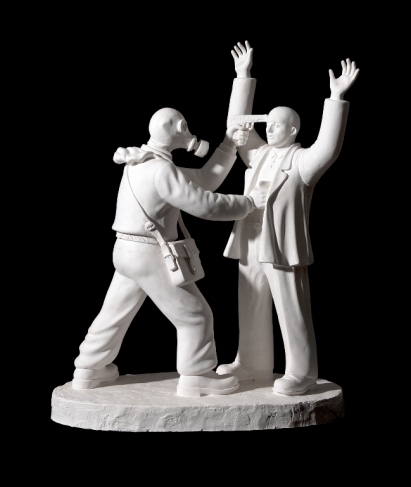

Grisha Bruskin. "Robbery". From "H-hour" series. A part of the installation. 2012. Courtesy of author

Grisha Bruskin. "Horseman in a Gas Mask". From "H-hour" series. A part of the installation. 2012. Courtesy of author

Grisha Bruskin. "Murderer". From "H-hour" series. A part of the installation. 2012. Courtesy of author

Grisha Bruskin. "Pilgrims". From "H-hour" series. A part of the installation. 2012. Courtesy of author

Grisha Bruskin. "Facial Measurement". From "H-hour" series. A part of the installation. 2012. Courtesy of author

Grisha Bruskin. "Twins". From "H-hour" series. A part of the installation. 2012. Courtesy of author

Grisha Bruskin. "Guardian of the Threshold #1". From "H-hour" series. A part of the installation. 2012. Courtesy of author

Grisha Bruskin. "Mice in a Cage". From "H-hour" series. A part of the installation. 2012. Courtesy of author

Moscow, 4.09.2012—3.10.2012

exhibition is over

Curator: Olga Sviblova

Assistant curator: Anna Zaitseva

The Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow, presents a solo exhibition by contemporary Russian artist Grisha Bruskin, who lives and works in New York and Moscow. His works can be seen in major museums worldwide, such as MoMA in New York, the Museum Ludwig (Cologne), Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, National Gallery of Art in Caracas, Art Institute of Chicago, State Russian Museum, State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, State Tretyakov Gallery, and others.

For the press

Grisha Bruskin’s new sculpture project ’H-Hour’ (2012) has no specific historical or geographical ties and examines the myth of the enemy in very diverse manifestations: the hostile state, class enemy, enemy of the subconscious, ’the other’ as enemy, Time, Chronos and Death as enemies, the Enemy of the Human Species, and so on.

Bruskin’s installation of several dozen sculptures plunges the viewer in the atmosphere of a strange Kafkaesque world where an emergency situation is in force. All the ’H-Hour’ sculptures — soldiers, people in gas masks, blind wanderers laden with suitcases and knapsacks, terrifying androgynes, mythological guardian creatures — are in one way or another related to the artist’s personal experiences. But the visual inspiration for them was neither direct impression from life nor high art, but on the contrary ’low’ art that is anonymous, collective and archetypical. Pictures found in the products of mass culture — in foreign language textbooks, civil defense posters and all kinds of instructions. The author identifies these pictures and endows them with his personal experience, giving them a new and different life. Even when the subject is ’high’, for example, melancholy (the melancholy androgynous warriors), the artist turns to the plasticity of primitive popular sculpture from the 16th to 18th centuries, rather than to the plasticity found in superior examples of West European Catholic sculpture from the same period.

In ’H-Hour’ the artist’s concerns are how the trivial is made sacred, how strong the hypnotic power of art and the image in general really is, and how depiction can become a means and instrument for manipulating human consciousness.

’As in my childhood, in the modern world a person’s life is spent, like the life in Valerio Zurlini’s movie ’The Desert of the Tartars’, in anticipation of the enemy. Real or mythical. That is why neither the time nor the geography is specified in ’H-Hour’. ’H-Hour’ is a parable about the enemy, manifested in absurd metaphors. Just as in the civil defense posters, ’H-Hour’ exists in an emergency situation. According to Giorgio Agamben, when the boundary between law and life is lost, both are lost, and the strange world of the state of exception arises, where law is superseded and human life turns into pure ’biology’, under the supervision of the expert bio-powers. In our times (the struggle against the enemy and, primarily, against international terrorism), the state of exception is no longer an exception but becoming the norm everywhere, including democratic countries. It is becoming routine. Today, arriving in Moscow or New York, the world seems to me in both places as it did when I was a child staring at civil defense posters, with the horror and stupor of an ’outsider’.’ (Grisha Bruskin)