Arrested

Jim Lee. Rescue. 2006. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

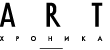

Jim Lee. Beachy Head / Washed Up. 1969. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

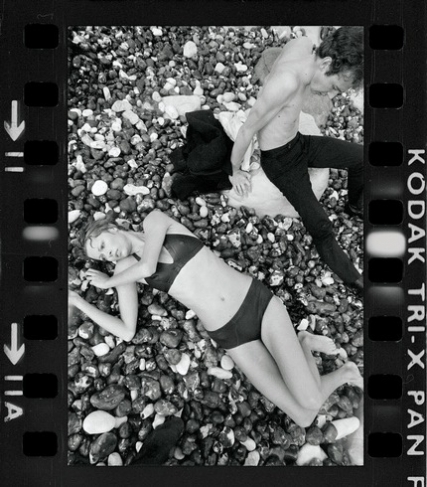

Jim Lee. Kenya / Beach. 1970. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

Jim Lee. Feather / Staircase. 2002. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

Jim Lee. Midget. 1968. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

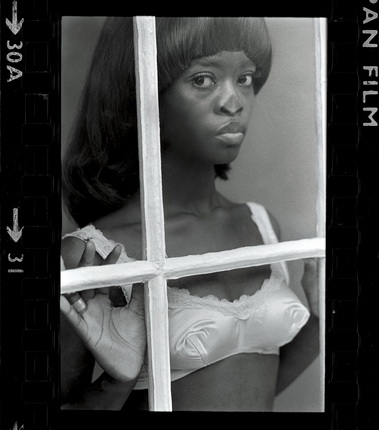

Jim Lee. Window. 1969. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

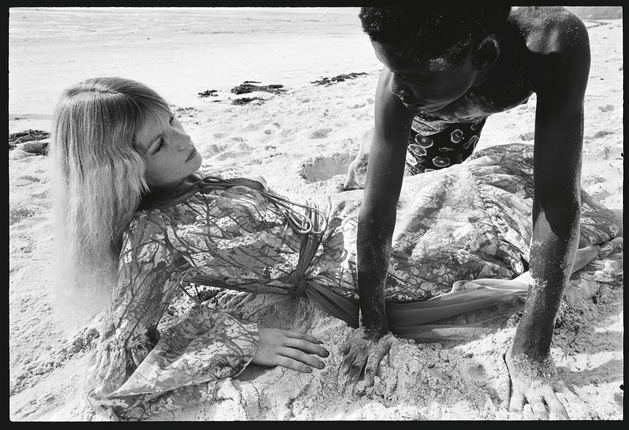

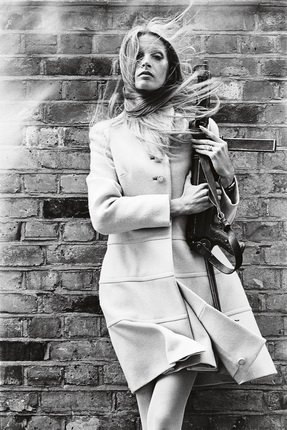

Jim Lee. Baader Meinhoff. 1969. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

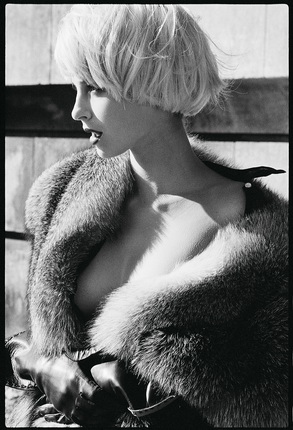

Jim Lee. Flesh. 2005. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

Jim Lee. Paris Collections. 1971. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

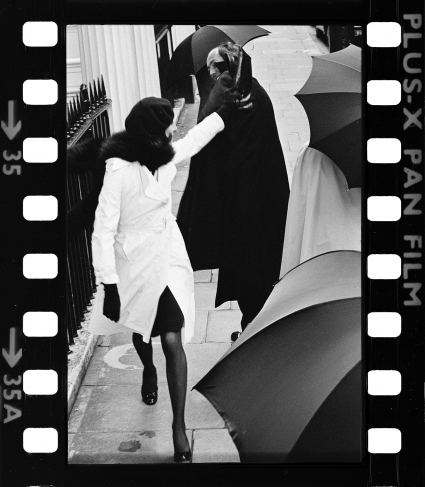

Jim Lee. Umbrella / Slap. 1974. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

Jim Lee, Pyjamas / Shaving, 1971, Artist’s collection, © Jim Lee

Jim Lee. Shimmering Light. 1974. Artist’s collection. © Jim Lee

Moscow, 15.03.2013—12.05.2013

exhibition is over

Ekaterina Cultural Foundation

21/5 Kuznetsky Most, porch 8, entrance from Bolshaya Lubyanka street (

opening hours: 11:00 - 20:00, day off - Monday.

Tel: +7 (495) 621-55-22

Share with friends

Curator: Olga Sviblova

For the press

François Truffaut once wrote that there are no good or bad movies, only good or bad directors. That was the upshot of his «politique des auteurs», his politics or policy of authorship, which was based on the idea that the force of a personal vision could subdue the money-making machinery of the film industry to its own ends—and that anyone whose vision had the force to prevail against that apparatus once could probably not help manifesting it always. Like Hollywood directors, fashion photographers are artisans in the service of a big machine. And likewise, fashion photography has its auteurs—its Avedons, its Bourdins, and so on—whose artistic sensibility is irrepressible. But they are rare; much rarer, in my experience, than their counterparts in the world of celluloid. In general, fashion photographers don’t seem to me to express any compelling desire that would be productively at odds with (without actually frustrating) the utilitarian task their employers have assigned them, that of stoking the passion for consumption. That’s not surprising, but it’s a bit disappointing. And it helps explain why, when I first came upon Jim Lee’s images for the first little more than four years ago, I experienced a kind of shock. Here was something really rare: imagery made under the aegis of the fashion industry but with content way too hot to be contained by the cool surfaces of desirable apparel or appeased by the anodyne comforts of shopping. Pictures embodying complex, ambivalent metaphors about love, war, identity, conflict. And all done with such a consummate sense of style that they could pass in the fashion world.

But how, I wondered, did pictures more interested in people than in the clothes they wear function as fashion photography? Precisely, I began to realize, thanks to something like that sense of shock I first experienced when seeing Lee’s photographs. It’s a shock of recognition, really—or (if such a thing can exist) a shock of empathy. I recall something that W.H. Auden once said: He was writing about the abstractness, the schematic character of the characters in the plays of George Bernard Shaw. Shaw’s characters, he complained, have no bodies. And then he added: Oscar Wilde’s characters don’t have bodies either, but at least they have clothes. Well, that brings us to the point about fashion photographs: The people in them rarely have bodies, they only have clothes. Not so with Lee however: Inside their clothes they have bodies and inside their bodies they have souls, and those souls are as ambivalent and needful and beautiful as anyone’s.

I see Lee’s attitude as the polar opposite to that of Helmut Newton. Newton is a mannerist; if the characters he portrays have an inner life it is rendered unknowable by the armour of their self-certainty, like the Duke of Urbino in Bronzino’s portrait in the Pitti Palace. They never lose their cool. Lee’s aesthetic is closer to the baroque. His people are capable of ecstasy, like Bernini’s Saint Teresa who came to mind when I first saw Lee’s Ossie Clark/Vietnam, 1969, or of despair, as in my favourite of his images, Bikini/Beachy Head, also from 1969. But maybe it’s presumptuous to even name the feelings these images evoke. Talking about the Beachy Head picture, Jim remarked to me that everyone who sees it sees a story in it—but each person sees a different story. Such pictures are mirrors in which we recognize something of ourselves. Does that recognition, that each viewer completes these photographs in his or her own images, contradict my definition of Lee as an auteur who stamps his own vision on the products of an industry that is in principle indifferent to it? Not really, not if you understand that a man’s vision can be generous and inclusive rather than imperious and solipsistic. As I’ve come to learn more about Lee’s work the breadth of empathy it embodies has become even more evident.

Barry Schwabsky