La Belle Dame sans Merci

Gabriella. 2011 @Alec Soth

Pale man (Villa Medici gardens). 2011 @Alec Soth

Lamia. 2011 @Alec Soth

Georgia. 2011 @Alec Soth

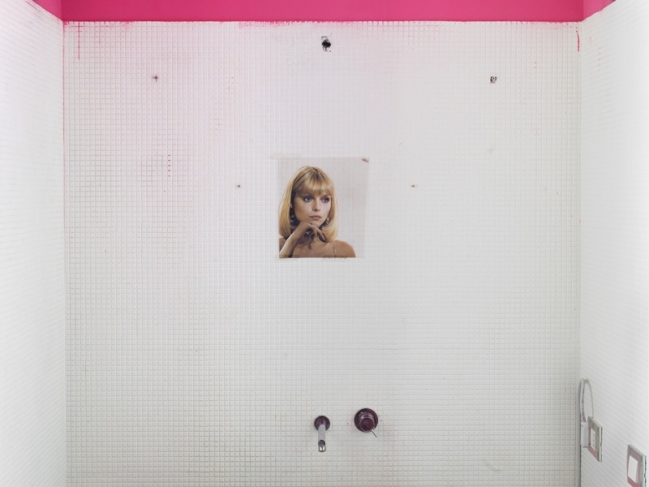

Michelle. 2011 @Alec Soth

Moscow, 30.03.2012—9.05.2012

exhibition is over

Central exhibition hall Manege

1, Manege Square (

www.moscowmanege.ru

Share with friends

Produced by FOTOGRAFIA International Festival of Rome and MACRO Museum

Curator: Marco Delogu

For the press

In 1930 Società Editrice La Cultura, based in Milan and Rome, published the first edition of La carne, la morte e il diavolo nella letteratura romantica, a fundamental text in modern comparative studies by the critic Mario Praz, which introduced new reading itineraries for texts by English, French and Italian writers. Chapter IV is entitled La belle dame sans merci, after the ballad by John Keats. Following several lines from the poem and a passage from Giuseppe Parini’s ode A Silvia, it continues «with an extremely obvious and bald statement. There have always existed Fatal Women both in mythology and in literature, since mythology and literature are imaginative reflections of the various aspects of real life, and real life has always provided more or less complete examples of arrogant and cruel female characters.» The English poet’s verses constitute one of the best-known artistic formulations of this theme and the work of Alec Soth in turn picks up the threads. It is a complicated intertwining of four subjects: beauty, eroticism, love and death, of which the last two can never be treated separately.

1) Beauty. «‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty’ — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know,» Keats wrote in Ode on a Grecian Urn, finding the highest expression of the term in a work of art. On the other hand, the famous theory of «Negative Capability» that he formulated in 1817 in a letter to his brothers George and Thomas, expressed the need to accept the fact that some matters may remain mysterious and unresolved, rejecting the fact-finding approach of science in favour of the artistic one, which deals with problems to explore them rather than solve them. The structure of Soth’s work is founded on its incompleteness, hinting through a series of formal connections (the portrait of a woman touching her belly is followed by one of a man in a similar position, and then the classical model of a Venus pudica), causal links (the scene of an individual bent over the steering wheel of a car after the picture of a coiled snake), and recurrent elements (the pineapple first held by a passer-by is depicted smashed on the ground and oozing juice a few pages later) at the presence of a narrative that is thwarted by an irresolvable lack of linearity. There are no explanations to find or destinations to reach, one must simply enjoy the process. As in sadomasochistic practices, pleasure lies in its postponement: there is no coitus. In describing the figures depicted around his imaginary urn, Keats lingers on the story of a young woman running away from a man who is following her and will never be able to reach her because the artist’s hand has trapped him for eternity in an immobile pose: «Bold lover, never, never canst thou kiss, / Though winning near the goal — yet do not grieve / She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss, / For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!». Desire can thus be perpetuated in time. This is the paradox of photography, which by immortalising its subjects gives them an impression of eternity.

2) Eroticism. There is no certainty that Keats’s belle dame can be identified as the young Fanny Brawne with whom he was falling in love at the time at which the ballad was written. However, there is no doubt that the letters that he started to write to her shortly afterwards shocked the prim Victorian morality when they were rediscovered and published in 1878, a full 57 years after the poet’s premature death. In one of the last missives that he sent his beloved in February 1820, before leaving England to seek an impossible remedy for his rapidly failing health in Italy: «In my present state of health I feel too much separated from you and could almost speak to you in the words of Lorenzo’s Ghost to Isabella. ‘Your Beauty grows upon me and I feel/ A greater love through all my essence steal’.» The turmoil regarded not only the self-righteous, but also those whose own writing was inspired by his words, from Oscar Wilde (who nonetheless bought a letter at auction) to Matthew Arnold and Algernon Swinburne, whose Laus Veneris displayed far more vices than the illustrious master and also more than he himself actually possessed. They were thus scandalised not by possible allusions to the flesh in the amorous relationship, but by the close encounter with a cultured man in his private sphere who was willing to abandon himself before the woman he desires. In this series Alec Soth collects together a huge sample of erotic expressions, from the most explicit image of a woman offering herself in a flowery meadow to the shower that can be taken every day in the company of a portrait of Michelle Pfeiffer in a house in Rome, and a composition of fruit that alludes at male and female genitals, bringing to mind the way Sarah Lucas synthesised the depiction of two bodies on an old mattress in Au Naturel, using two oranges and a cucumber for the man and a bucket beneath two melons for the woman.

3) Love and Death. This is not the first time that Alec Soth has addressed the theme of love. For the series that inspired the name of his second monograph, Niagara, he travelled to the border between the United States and Canada, in the footsteps of the couples who decide to get married or simply spend a few hours together at the Falls, taking advantage of the many motels with marriage suites that have grown up for the purpose in the area. Alongside the endless North American landscapes, the photographs from this project include the faces of the lovers, their nude bodies and also a few passionate letters that the photographer collected with the spirit of a butterfly hunter. The spectre of death appears on the horizon because the same scene chosen by many for their wedding is also a favourite spot for suicide attempts, with people flocking from all over the country to hurl themselves into the icy waters, to the extent that a local agency was established in 2003 to try to stem the constantly growing phenomenon. Nonetheless, Soth’s photographs bear no explicit references to this tragic migration, which remains a distant echo each time that the terrifying grandeur of nature is depicted. This is not the case in La belle dame sans merci. Here the love-death dichotomy is the main impulse that allows the sequence to advance, or rather to slow, accelerate or turn around on itself in a fragmented elliptical progression. The embodiment of this dual nature, according to the dominant male point of view, is the femme fatale; the serpent, which appears around the middle of the series, is her unequivocal symbol. The title of this image is Lamia, after the half-woman and half-animal figures of Greek mythology that seduced young men to feed on their blood. Lamia is also the title of a poem written by Keats in 1819, which recites: «Her head was serpent, but ah, bitter-sweet! / She had a woman’s mouth with all its pearls complete: / And for her eyes: what could such eyes do there / But weep, and weep, that they were born so fair? / As Proserpine still weeps for her Sicilian air. / Her throat was serpent, but the words she spake /Came, as through bubbling honey, for Love’s sake . . . ».

Keats often wrote poems as a tribute to specific works and figures in more or less recent history, as the case of his early Imitation of Spenser (1814) and On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer (1816), and Alec Soth follows a similar criterion, resting the foundations of his series on the bases provided by the English poet. However, the origins of his LBDSM go deeper, for the solid Keatsian platform is overwritten by a further level of quotations and references to many other sources. Additionally, the still life with a bowl and three fruits in the middle can be traced to the verse of Tony Harrison in A Kumquat for John Keats and an apparently ordinary urban scene turns out to be the partial reconstruction of Ruth Orkin’s photograph entitled An American Girl in Italy, taken in Florence in 1954 and depicting a young woman besieged by the gazes of the men around her. It is a covert declaration of the process that Soth developed to achieve these pictures, exploiting the possibilities of control and representation permitted by the technique of «staged photography» instead of limiting himself — as he has done more often — to recording the reality before him without intervening in any way. This excessive adherence to the model has resulted in the suspension of private images with the quality that is normally (and naively) attributed to any photograph, i.e. veracity. The result is a sensation of reawakening from a dream, exactly as experienced by the subject of Keats’s ballad, towards the end: that which undisputedly belonged to reality up until a moment earlier reveals itself to be an imitation of it, whose adherence to the original crumbles at the moment in which the paradigm of the representational device is abandoned. In addition to those already mentioned, Soth’s references also include several allusions to ancient art, the inevitable basis for any form of Romanticism from Homer to the Middle Ages. Between a pair of busts and a Maternity on a street corner, the most explicit is the Venus pudica mentioned earlier. The gesture that she is making is extremely ambiguous for it is unclear whether she is covering her genitals or stimulating them. She is the Aphrodite of Cnidus, probably the best-known sculpture by Praxiteles, now lost like almost all his works. This means that Soth placed a copy — the best preserved one, belonging to the enormous Ludovisi collection — in the centre of his viewfinder and used his camera to make a further duplicate, or rather a unique interpretation mediated by himself and the rules of the language that he uses.

Keats died on 23 February 1821 in Rome, where his tomb still stands, bearing the famous epitaph «Here Lies One Whose Name Was Writ in Water». Soth sets his LBDSM in Rome, hinting at a fanciful biographical reconstruction and at the same time reconsidering the most typical ways of applying photography to the task of reviewing an area. In fact the result is a project that bears in mind the intention of representing the City of Rome, but updates the method of research on the landscape according to a logic by which the exploration of places occurs in the background of other observations that are performed in the foreground. The city is part of the mystery that this work cannot reveal entirely, but only capture particles. Consequently, the enigma of a pineapple that reoccurs twice in sequence and is chosen as a decorative motif for the end-papers of the book is impenetrable like the presence of the same tropical fruit in a Roman mosaic floor at the Palazzo Massimo alla Terme, whose dating, between the first century BC and the first century AD., is many centuries earlier than the European voyages of discovery to the Americas.

Francesco Zanot