The big wheel keeps on turning

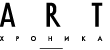

Marc Quinn. The Eye of History (Atlantic Perspective). Points of Continent. 2012. Oil on canvas. Ø 220 cm. © Marc Quinn Group. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

Marc Quinn. Where the Worlds meet the Mind (TC180). 2012. Oil on canvas. © Marc Quinn Group. Photo: Marc Quinn Studio. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

Marc Quinn. The Eye of History (Bering Strait) Reversal. 2012. Oil on canvas. © Marc Quinn Group. Photo: Marc Quinn Studio. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

Marc Quinn. Chromatic Labyrinth. MQ 180. 2011. Oil, acrylic and silicon on canvas. 180 x 107 cm. © Marc Quinn Group. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

Marc Quinn. The World of Abstraction. 2012. Oil on canvas. © Marc Quinn Group. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

Marc Quinn. A Moment of Clarity. 2010. Orbital-sanded and flap-wheeled lacquered bronze. 180 x 65 x 54 cm. © Marc Quinn Group. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

Marc Quinn. Life Breathes the Breath. (In). 2012. Orbital-sanded and flap-wheeled lacquered bronze. 73 x 69 x 53 cm. Work © Marc Quinn Group. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

Marc Quinn. The Origin of the World. (Cassis madagascariensis). Indian Ocean, 310. 2012. Bronze. 270 x 310 x 236 cm. © Marc Quinn Group. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

Marc Quinn. Vice as an Object of Virtue. 2010. Silver. 87 x 51 x 23 cm. © Marc Quinn Group. Photo: Marc Quinn Studio. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

Marc Quinn. Stealth Kate. 2010. Painted bronze. 88 x 65 x 50 cm. © Marc Quinn Group. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

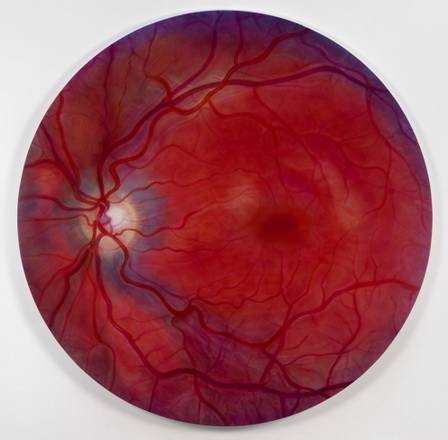

Marc Quinn. History Painting, 2011. 2011. Oil on canvas. 208 x 134 cm. © Marc Quinn Group. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography. Courtesy: Marc Quinn Studio

Moscow, 26.10.2012—14.12.2012

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Curator: Olga Sviblova

Assistant curator: Anna Zaitseva

«The Big Wheel Keeps on Turning is the story of the planet and everything that lives on it. It is our lives in time. Like the spiral of a shell, the world is in constant revolution»

Marc Quinn.

Video

In english (1 h. 24 min.)" style="margin-bottom:7px;" />

In english (1 h. 24 min.)" style="margin-bottom:7px;" />

For the press

Marc Quinn (b. 1964) belongs to the generation of Young British Artists who not only radically changed the British art scene, but became one of the most important artistic tendencies to influence the development of world art in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Marc Quinn’s oeuvre is based on a serious philosophical understanding of the history of art, the history of culture and the reality in which we live today. At the same time he works splendidly with the most diverse materials and media. Whether it is sculpture, painting or art installation, in all his creations Marc Quinn examines elementary questions of the universe, and the principles by which man exists in this world.

The title of this exhibition, The Big Wheel Keeps On Turning, refers to ’the history of the planet Earth and everything that exists on it’. In Quinn’s own words, ’human beings are very grand and think they’re above everything, but in fact we’re connected to everything else’.

In a virtuoso combination of art and science Quinn examines human and natural forms, but always remains true to scale, expressing issues of life and death, beauty and ugliness, eternity and the passing moment.

Marc Quinn’s vision is stoical, not in the usual clichéd meaning of the word, but in the sense that he belongs to a philosophical tradition that sees humanity’s pursuit of earthly glory as pointless and insignificant when set against the vastness of the cosmos. Just as the tectonic shifts of land masses shown on Quinn’s map paintings are indifferent to mankind’s earthbound activity, so the spirals on his bronze shells record the passing of geological time within which humanity passes in the blink of an eye.

Quinn’s works are always within the context of the broader artistic tradition. His hyper-real flower paintings offer a new perspective on the vanitas tradition of seventeenth-century Dutch still-life painting. The Complete Marbles series

Exhibitions of Marc Quinn’s art have been held in major museums worldwide, including the Tate Britain (1995), Kunstverein Hannover (1999), the Fondazione Prada in Milan (2000), Tate Liverpool (2002), the Irish Museum of Modern Art (2004), MACRO (2006), DHC/ART Fondation pour l’art contemporain in Montreal (2007), the Fondation Beyeler, Basle (2009) and Oceanographic Museum, Monaco (2012).

OS: When did you decide to be an artist?

MQ: I made artworks when I was a child and at school, and I guess the older I got the more I wanted to do it, so I didn’t ever really do anything else. It was just in my nature. I was always fascinated by materials in the world, I’m interested in how all the atoms of the world combine to make all the different things in the world, including us.

OS: One of your first pieces — and one of the most well-known — is your head with your own blood in it.

MQ: Yes, I wanted to look at that boundary between art and life, to make an artwork that was about the difference between an object and a living person, and this sculpture is of my head,cast in my own blood that I took from my body over the course of a year. In the head there’s the same amount as in the whole body — it’s nothing else, it’s just frozen blood. So it’s the shape of my head, it’s made from my body, but it’s still not a living thing.

OS: In Russia people there’s an expression ‘I paid with my blood, I paid with my life’. It’s really a materialisation of this metaphor.

MQ: Yes, and of the romantic metaphor that the artist should suffer to make art. As you say, you’ve actually taken your body to make art. But five of these sculptures now exist, and I’m still alive although there’s fifty pints of my blood in the world. So it’s also about the miracleof the regeneration of the body — I can take all the blood out to make a sculpture, and my body makes more. Nature is always remaking itself, and the world is always remaking itself, and we live in the medium of time, so nothing is ever the same, we’re always moving.

OS: And moving in nature too.

MQ: And humanity is both in control of and controlled by nature. I made a new piece for a show in Monaco that’s a block of ice from the North Pole. It was brought from there by Prince Albert II on an expedition, and he gave it to me to make this sculpture. It’s in a plastic bag in a display freezer, a bit like the blood head, it’s never been defrosted, and of course the paradox is: in order to keep it frozen you’re using a refrigerator, which is using electricity and producing gases that contribute to the global warming which is destroying the North Pole. This is the human paradox in relation with our planet, that we’re preserving and destroying at the same time. Hopefully, if we preserve more than we destroy, then we’ll be all right. I think the planet will always be all right. If we do something stupid, then in a million years’ time the planet will find a new balance and start again, but trying to find a way humans can coexist with nature is really one of the big questions of the 21st century, I think.

OS: We are both limited and unlimited in a metaphysical way, and this is the problem you frequently touch on in your art. Like in your ‘Flowers’ series.

MQ: Exactly, a flower is something that lasts a very short time, it is perfect for a moment and then will decay and disappear, like we do, but of course it’s much quicker with a flower, so in a way they’re capturing and celebrating the beauty of the moment. But in celebrating that they also make you think of the past and the future.

OS: Your first ‘Flowers’ sculptures were also frozen. Why did you freeze them?

MQ: When I made the blood head, I had to resolve the technical issues of how to preserve it. If you left the blood head in a normal freezer it would turn to powder, because the frozen air sucks all the moisture out of it. In the end the way to solve it is to put the head in frozen silicone oil, because this stops the air getting to it. Then I thought, well, if you can preserve the head like that, what else can you freeze in the same way? So I put a flower in a little jam pot of frozen silicone oil in my freezer, and I left it for a year. I came back, pulled it out, and the flower was exactly the same. And I thought, wow, that’s amazing, because you’re killing but also immortalising at the same time, preserving that most delicate thing. So from then on I started to make these frozen flower sculptures, like a bunch of flowers frozen, and then for Miuccia Prada in Milan I made a whole garden that was frozen. New ideas often come from trying to solve problems with the works that go before.

OS: And then you started to make paintings of the frozen flowers?

MQ: Exactly, and then to make paintings of fresh flowers. I go to the market and buy whatever flowers they have on that day — all these flowers that should never be growing at this time of year, or growing together, but because of human desire they’re flown in from all over the world. And then I get the flowers and make a little sculpture and take a photograph of it. The next day the sculpture is brown, but I paint from the photograph. So those paintings are really paintings of ephemeral sculptures made of flowers. Because I never change the composition in the painting, it’s always a painting of what I made. It’s about how we blur the boundaries of what is natural and what’s not.

OS: How do you integrate photography into your work?

MQ: What I love about photography is that it compresses time into a single image. Photographs are about freezing time. To me, a photograph is like a frozen sculpture, they’re both about taking a moment out of time. Those are paintings from photographs, but to just take the photograph and put paint on top holds no interest for me. When you do a photo-realistic painting, you put time into this moment again, because it’s taken three weeks, a month,to paint this photograph that actually took a moment. So you’re playing again the idea with fast and slow, the instant and something that takes time.

OS: Genetics is another recurring theme in your work, and this is present in the recent sculptures produced from three-dimensional scans.

MQ: Exactly. When you make the shell, for example, or the rabbit, you scan the object and that becomes a code in the computer, which is equivalent to DNA code in us, and then that code is fed into a machine that makes the sculpture. So it’s very similar to the way we are made. The instructions to make us, the genetic code, is put into the woman’s reproductive system, where the code is played out in a biological machine to create another human. The scanning process is a good metaphor for the way nature creates things, and it’s interesting to use it. I don’t like it when people use technology to make something about technology. I want someone to look at that shell sculpture, not know how it’s made and just think, just feel it as an artwork. The fact that you couldn’t have made it five years ago is interesting to me, but it has to be secondary to it being good artwork.

OS: And in the big series of sculptures you repeat the same work in different materials and at different scales. It’s one of the most exciting things in your creation for me, that you can use gold, silver, bronze, plastic in various sizes, and the same sculpture is seen in a totally different way. It’s like a different schema, and it totally changes our impression. How did it start?

MQ: When I made the sculptures of disabled people. I was in the British Museum looking at the fragmented antiquities, and all the people were looking and saying ‘Oh, these sculptures are so beautiful!’ And it struck me that if someone whose real body was shaped like that came into the room, then probably they’d have the opposite reaction, be embarrassed, not know how to deal with it, not even know how to speak to the person. So I thought maybe it would be interesting to make marble sculptures of these people who have different kinds of bodies, and it became a project about celebrating different kinds of beauty. The final piece in that series was the colossal Alison Lapper Pregnant that was in Trafalgar Square for two years. Then for the Paralympics in August they made a

OS: It was also incredible to put this sculpture in the middle of the old city where heroes normally stand. Trafalgar Square is a podium for heroes, so you created a new hero in some way.

MQ: Yes, definitely, and the other thing you’ve got to remember about all the sculptures that existed there is that they were about the past, because they celebrate someone who’s done something. And to me the Alison sculpture, because she was pregnant as well, is about the future. So it’s celebrating the possibility of heroes in the future. It’s taking something that’s looking back, and making it look forward as well. But when you do something in a public place, you connect with such a wide variety of people who would never go to a museum or a gallery, and so there’s an amazing connection. I think art is about communicating with a wide variety of people. It should be a mass media thing like cinema or fashion. And I think it’s changing, art in England is no longer something only a few people know about.

OS: So you are not afraid to say that you would like to create a piece that can communicate with the wider public.

MQ: Of course not. When I did the Alison Lapper, you saw that most people don’t have to be educated in art to have feelings.

OS: If you touch the basic problems, for example, life and death, past and future, people can feel contemporary art without special preparation.

MQ: Exactly, I completely agree.

OS: And your human sculptures are always of a real person?

MQ: Of course, yes. It’s always about finding a real person. After the disabled series I thought, what’s the opposite of finding surprising beauty? And it had to be someone that everyone agrees is the most beautiful, perfect person in the world. It couldn’t be a movie star, it had to be someone who doesn’t speak, who’s only image. And then I thought of Kate Moss, who at the time she was at the height of her fame — well, she’s still very famous — though she doesn’t say anything, she’s pure image. The sculpture I made is not really about her as a person, it’s a sculpture of the image that we’ve collectively created, this unconscious idea of the perfect person. It’s like a hallucination, the way we create images collectively, and then forget that we created them. You open a Vogue and there’s a picture of someone that looks so perfect, and everyone thinks ‘Ah, I look terrible compared to that’. But actually the real person in the photo doesn’t look like the photo, either. That person doesn’t exist. Thinking about how people try and make themselves into something that doesn’t exist led the next body of work that I did, which is the plastic surgery people. People who change themselves completely, to make their bodies fit into either a cultural idea or an idea they have in their own mind. So there’s a natural evolution from the disabled series, through Kate, to the plastic surgery. It’s all about body image and how we relate to it.

OS: It’s also rather like the problem of classic art, where people have a beautiful body, beautiful proportions, but they don’t have faces, because expression arrived much later in the Renaissance, when they started to be interested in personality.

MQ: Although in Roman portraiture you have very strong portraits of people that are very much personal portraits. Less so in Greek art. But I agree, and I think the other thing about the Kate sculptures is that really they’re masks, or screens that people project their fantasies and aspirations onto. That’s why I made one in solid gold, to symbolise perfection and impossible riches, things people wreck their lives trying to achieve.

OS: And then the black version is just a shadow, a symbol of our illusion?

MQ: Yes, exactly, it’s like the unconscious version, the version we don’t really see is there, in the way that whatever you do, you’re always followed by cultural things you’re not

even aware of.

OS: This interplay between the conscious and unconscious also exists in the series you created with the eye, the retina and the iris. Of course you can read our problems, our state of health, from the iris.

MQ: Yes, but the iris is also beautiful. I’m interested in where abstraction and figurativeness meet, the uniqueness. You look at an eye up close, and whatever colour the eye first seems, there are all these beautiful lines and colours. The circle is like a mandala, one of those meditation paintings from India that you can look at for a long, long time. And then in the middle you have this black hole that can symbolise the mystery of life, but also the mystery of someone else. It’s a cliché, but it’s the door between the outside world and someone’s inner world.

OS: And then in the ‘Eye of History’ series, you started to combine the form of the eye with the map of the world.

MQ: In a way, that’s about the whole paranoia of life. Now that we have

OS: So it’s a material presentation of globalisation, how our feelings towards our environment are changing.

MQ: Exactly, they’re all related to things I was talking about earlier, about our relationship to the planet, but also the globalisation issue, our relationship to other people in the world and our relationship to the planet. It’s a really simple idea — the eye and the globe are both round, what happens if you put one on top of the other? And I really liked the result.

OS: When you read books on psychology or biology, they say eyes are a piece of our brain present on the outside.

MQ: That’s why I did the retina, because actually a retina, which is at the back of the eye, is the bit where our brains and central nervous system meet the world. It’s where the light hits. The light goes through your pupil and it’s that screen at the back where light gets translated into the nervous system, which gets translated into the image in our head. So really the real border between the world and us is not the pupil, it’s the retina.

OS: And then we see today your new, big paintings. There’s meat and people, one person, a few people underwater. How do these ideas connect?

MQ: I like finding things — I don’t like inventing things. So I was just cutting some meat and looking inside, and it’s just so beautiful when you look at the colours of the meat and the shape, the marbling of the fat and everything. Obviously there’s great symbolism as well, through centuries of Christian art. I just cut the meat up, took a photograph and then made a painting. To me it’s like a tiny bit of a Rembrandt or a tiny bit of a Soutine or Francis Bacon, but blown up, and you get this thing that is kind of beautiful and terrible at the same time. And then for the underwater ones, I got a diver to go under the waves in Australia and I said to him, take three hundred pictures, and when he’d taken them all

I went through them. I just chose the ones I really liked and made paintings of them. And then there’s this zone where the waves crash, where things seem to be being destroyed or created. You have these bubbles like crowds. It’s a mythical space: are the people dissolving or are they emerging? So again it’s this whole sense of something appearing and disappearing, which is something I like as well, and somehow the two together, there’s something beautiful about it. Maybe one of them is about our flesh, the fact that we’re flesh, and the other one suggests we’re more than flesh, and somehow together they work quite interestingly. Sometimes I don’t understand what I’m doing until it’s done, and I think that’s good — I mean ‘understand’ in the sense that I can’t exactly verbalise it. It’s always about working on instinct.

OS: And now you’ve made T-shirts of the eyes and flowers, they are accessible to everyone,adults and children.

MQ: That’s why I made the T-shirts and the tattoos and things. Because I want my images to go out in the real world, and to be part of life, not just something you keep in a museum or

a collection. What I like about the temporary tattoos is that a tattoo’s supposed to be about permanence, but I think life’s all about change, and somehow the idea of making something that’s permanent into something you change all the time sums up my ideas about life.

OS: Your recent self-portrait is a close-up of your eyes and face. Why?

MQ: I did all these works about the riots in London, and about the hoodies, and somehow I always feel that an artist should be an outsider, an outlaw in some way, so in a way that painting is a self-portrait of the position of the artist in relation to society.

OS: At the other end of the scale, your giant water sculpture was a major construction project.

MQ: The eye in the water was on such a scale that it had to work with nature, this river in Norway, but it’s also about time, as the river passes through and changes. It’s always the same but it’s always changing. So it’s about time in a way, again. And the human relationship to nature in terms of our input into the world.

OS: Your studio is full of your own pieces, either finished or in progress, and there are also a lot of sculptures from different cultures, from different periods, mostly from many hundreds of years ago. How did you collect them, and when did you start collecting?

MQ: I’m sitting in my studio and looking at this sculpture that was made 2,000 years ago, and I know nothing about the artist, how it came into being, or precisely what it was intended to mean. It’s a Buddhist statue that somehow celebrates something about the human condition and it speaks to me in the present moment. All great art is a time machine, so

even though this statue was made 2,000 years ago it’s totally in this moment and it’s talking to us. And I don’t know who made it, but I’m communicating with that person. When I was younger I loved to go to the British Museum and other museums to look at things. And later on, I realised that you can still buy things like this. The first collectors I met had been collecting since the 1930s, and eventually I started to buy some works from them, and now I have the privilege of being able to live with these works while I’m working, which is an amazing thing and kind of inspires me in my own work.

OS: People say you are a provocative artist, you are presented as one of the stars of the famous YBA movement, but at the same time your work is very classic.

MQ: Yes, very classic. I mean, I was always interested in art. I did History of Art at university, I didn’t go to art school, and I just love everything about art from all different cultures. I think of art as the flower of the human spirit. But it’s a flower that doesn’t die. It’s a kind of permanent celebration of the beauty inside people, and we’re looking at these old things and they’re telling us about what people cared about 2,000 years ago, and somehow that’s a continuation. That to me is very moving and life-affirming.