Alexander Rodchenko

Alexander Rodchenko Pioneer Girl. 1930 Collection of the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive / Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Alexander Rodchenko Stairs. 1930. Collection of the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive / Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

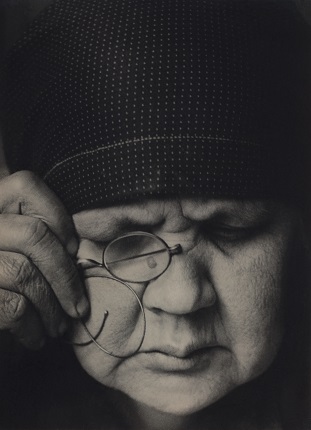

Alexander Rodchenko Portrait of the Artist’s Mother. 1924. Collection of the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive / Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

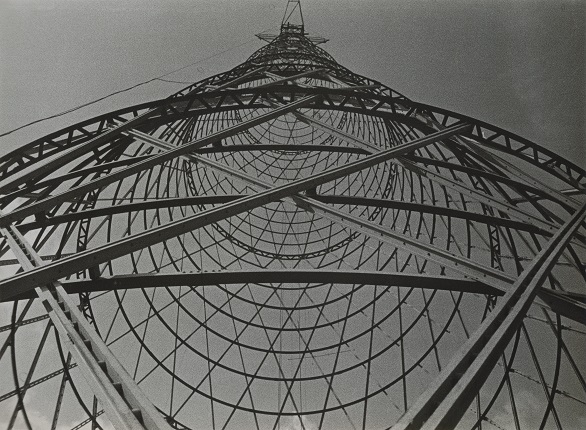

Alexander Rodchenko The Shukhov tower. Moscow. 1929. Collection of the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive / Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Alexander Rodchenko Fire Escape (with a man). From the series “House in Miasnitskaya St”. 1925. Collection of the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive / Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

La Gacilly, 1.06.2019—30.09.2019

exhibition is over

Maison de la Photographie de la Gacilly

Place de la Ferronnerie, La Gacilly, France

Share with friends

For the press

Alexander Rodchenko. Generator of Art

The Russian avant-garde of the twentieth century is a unique phenomenon not only in Russian, but in world culture. The amazing creative energy accumulated by the artists of this great age is still providing nourishment for artistic culture today and all who have dealings with the art produced by Russian Art Nouveau. Alexander Rodchenko was indisputably one of the main generators of creative ideas and the general spiritual aura of the age. Painting, design, theatre, cinema, typography and photography, all areas invaded by the powerful talent of this strong, handsome man, were transformed, opening up radically new paths of development.

The early 1920s was an «intermediate age», to quote Viktor Shklovsky, one of the finest critics and theoreticians of the day, a period when, albeit briefly, illusively, there was a resonance between artistic and social experiment. It was at this time, 1924, that photography was invaded by Alexander Rodchenko, already a well-known artist with the slogan «Our duty is to experiment» placed firmly at the centre of his aesthetic. The result of this invasion was a fundamental change of ideas about the nature of photography and the role of the photographer. Conceptual thinking was introduced into photography. Instead of just being the reflection of reality, photography also became a device for the visual representation of dynamic intellectual constructions.

Rodchenko introduced Constructivist ideology into photography and developed methods and instruments for applying it. The devices discovered by him spread rapidly. They were used by pupils and like-minded practitioners, as well as aesthetic and political adversaries. The use of the «Rodchenko method», which included the diagonal composition, discovered by him, as well as foreshortening and other devices, did not automatically guarantee the artistic dimension of a work, however. The practice of Rodchenko the photographer was confused not only and not so much by the formal devices for which he was so mercilessly criticised in the late twenties, as by the profound inner romanticism characteristic of him even in his student years. Suffice it to recall the make-believe letters he wrote to Varvara Stepanova in the early years after they met. This romantic element, embedded in the childhood which he spent back-stage in the theatre where his father worked, was transformed into the powerful utopian thinking of Rodchenko the Constructivist, who believed in the possibility of a positive transfiguration of the world and mankind.

In the 1920s in each new photographic series Rodchenko set new tasks and produced manifestoes on what photography and life would be like after they had been transformed by the Constructivist artistic principle. In the 1930s, particularly towards the end, exhausted by criticism and persecution, he tried to analyse life and artistic practice, his own included, the evolution of which was determined largely by the developing aesthetics of socialist realism. Incidentally, in the whole history of Russian photography of the first half of the twentieth century Alexander Rodchenko is the only person who, thanks to his printed articles and diaries, left unique records, artistic reflections by a photographer-thinker who witnessed historical cataclysms, which generated within him a tragic conflict of conscious premises and the unconscious drive to create.

Tired of the constant revolutionary transformations that produced a reality far from the ideals which had inspired his early period of creativity, he wrote in his diary on 12 February 1943: «Art is service of the people, but the people are being led goodness knows where. I want to lead the people to art, not use art to lead them somewhere. Was I born too early or too late? Art must be separate from politics ...»

In the final years of his life, betrayed by friends and pupils, deprived of the right to work and earn his living or take part in exhibitions, expelled from the Union of Artists, and in very poor health, Alexander Rodchenko was nevertheless a very fortunate man. He had a family: his friend and comrade-in-arms Varvara Stepanova, his daughter Varvara Rodchenko, her husband Nikolai Lavrentiev, his grandson Alexander Lavrentiev and his family, a small, but very close-knit clan charged with creative energy. If it had not been for this family Russia’s first photographic museum, the Moscow House of Photography, might never have appeared. In Rodchenko’s house, together with the Rodchenko family, we have discovered and studied the history of Russian photography, which would be unthinkable without Alexander Mikhailovich Rodchenko.

Olga Sviblova

The Industrial World through the Eyes of Alexander Rodchenko.

The Institute for Artistic Culture was founded in Bolshevik Russia in 1920. Alexander Rodchenko took an active part in the work of this institute and devised the slogan ‘ART IN PRODUCTION’. Rodchenko headed the metalwork faculty at the institute (amazons of the Russian avant-garde Lyubov Popova and Varvara Stepanova took charge of the textiles faculty, outstanding architect Victor Vesnin the architecture faculty and artist Anton Lavinsky presided over ceramics). Another slogan put forward by Rodchenko for the institute’s activities was ‘Long live production!’ Production and all related work processes were the new religion of Soviet modernism.

The constructivist Alexander Rodchenko created art objects that were to play a functional part in everyday life (Rodchenko’s ceramic sets of the early 20s, the famous Alexander Rodchenko Workers’ Club realised and exhibited in 1925 by the great architect Konstantin Melnikov for the Russian Pavilion in Paris, etc.). From 1923, when Rodchenko took up photography, he turned his camera to everything associated with production, often using the resulting material for his celebrated photomontages.

Faith in production and the constructive transformation of life was a shared belief among all those working in the Russian avant-garde. Production processes became the main theme of Dziga Vertov’s legendary documentary film almanacs. Rodchenko actively collaborated with Dziga Vertov and in particular he created photomontage posters for Cine-Eye and designed text captions for Kino-Pravda. Sergei Eisenstein’s films such as ‘Strike’, ‘October’ and ‘Battleship Potemkin’ are ‘interwoven’ with production processes. The rhythms of the movement of machines and mechanisms fascinated the Russian modernists, whose work looked towards the future. Rodchenko, for whom the future was the meaning of life and activity in the present, wrote: ‘I am so interested by the future that I want to see it immediately, a few years ahead’.

While photographing production, Rodchenko developed a special aesthetics for shooting these images. Unexpected foreshortening and diagonal compositions intensified the dynamics of the frame, and allowed the static image to convey the speed and magical beauty of rhythmic movement. Large-scale perspectives gave the leading role to the production process itself and to the images of people participating in that process.

Rodchenko published his experimental foreshortened pictures in the magazines Soviet Cinema, Novy Lef [Journal of the Left Front], 30 Days, Radio Listener, Let’s Produce!, USSR in Construction, etc.

Literally everything provided material for Rodchenko’s photographic features on labour and production processes: car assembly at the AMO plant, generators at the MoGES power plant, new constructivist buildings erected in the Soviet Union by modernist architects in the 1920s, the manufacture of light bulbs, newspaper production at a printing press, etc.

Rodchenko dreamed of working not just in photography, but also as a cinema director and cameraman. This opportunity presented itself in 1930, when he was commissioned by the Culture-Film factory to accompany a film crew to the Nizhny Novgorod region to shoot the film ‘Chemical Treatment of the Forest’, according to his own plan and screenplay. However, all the equipment issued at the studio proved faulty. Only Rodchenko’s Leica and his Sept compact camera worked as expected (Alexander Rodchenko purchased the latter during his only trip to Paris, in 1925). As a result a photographic series entitled ‘Stacking at the Vakhtan Sawmill’ was produced, instead of the projected film. It was later included in many exhibitions and repeatedly printed in various publications. In the photographs of this series, as in other pictures of production processes, Rodchenko accumulated the principles he developed in his abstract paintings from 1918 to the 1920s.

Like many other figures of the Russian avant-garde, Rodchenko declared that he was eager to serve Soviet production, seeing it as the most important mechanism for implementing the ideas of the Revolution. In 1922 Rodchenko designed himself a special design engineer suit, which was sewn by his wife Varvara Stepanova. Alas, the dreams of the Russian avant-garde very soon came into conflict with the reality of how life and production was developing in the land of the Soviets. The constructivist Rodchenko dreamed of free creative labour by proletarians working for the glory of the future, and in 1933 he was sent to make a photo report on the prisoners who built the White Sea Canal (one of the largest camps of Stalin’s GULAG).

Rodchenko was never a prisoner in the Gulag, but persecution against him started in the early 1930s. The experiments of the Russian avant-garde came to an end in 1932, with the Decree on Socialist Realism as a single form obligatory for Soviet culture in general, for painting, literature, music, theatre, cinema and photography.

At the White Sea Canal Alexander Rodchenko photographed prisoners working in terrible conditions, sometimes to the music of an orchestra also comprised of prisoners. Rodchenko was meant to use his images for photomontages reflecting the heroism of this ‘construction of the century’ for the magazine ‘USSR in Construction’. However, even in photomontages the exhausted faces of the prisoners speak for themselves.

From 1937, the apogee of the Stalinist repressions, Rodchenko was beginning to lose assignments for the Soviet press, and at that time in the USSR the only possible work was at the request of the Soviet authorities. Rodchenko was practically unemployed from the 1940s onwards, and in 1951 he was expelled from the Union of Artists, which completely deprived him of the right to work and participate in artistic life. After the death of Stalin in 1955 Rodchenko was rehabilitated as a member of the Union of Artists, but died shortly afterwards, in 1956. To the end of his days Alexander Rodchenko was never allowed a solo exhibition of his work.