Guest workers

Moscow, 22.03.2011—17.04.2011

exhibition is over

Moscow Museum of Modern Art

17 Ermolaevsky lane (

www.mmoma.ru

Share with friends

Presented by the Museum “Moscow House of Photography”

For the press

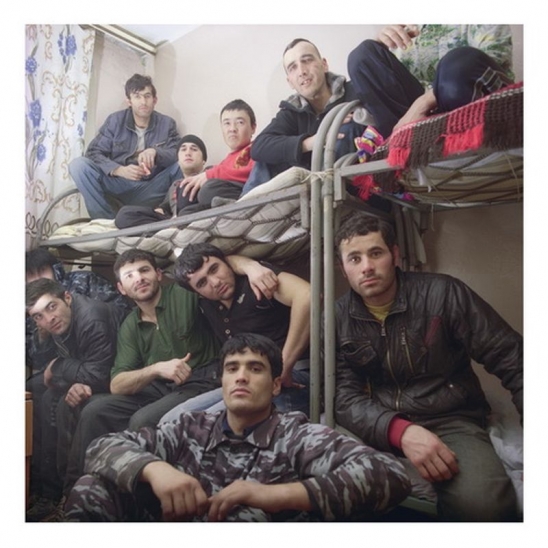

Sergei Chilikov is a photographer-philosopher, a photographer-director. His photographic method is the living picture, natural mise-en-scene, documentary theatre. In his last series shot in 2009 Chilikov photographs migrant workers in Aprelevka, just outside Moscow, on the construction site of a foam-concrete house. These Tajik labourers are all very cheerful, clad in sports and camouflage gear, playing up to the photographer and smiling at the camera as they arrange their spades in a row and halt their wheelbarrows for the picture. The migrant workers that appeared in Russia in the 1990s have today become common but indispensable as both street heroes and characters in popular anecdotes, with Russia occupying first place worldwide as a host country for the foreign workforce from Central Asia, Moldavia and Ukraine. Gastarbeiter— guest workers — is another series in Chilikov's catalogue of jobs and professions, where we have already encountered market traders and supermarket assistants, factory workers producing furs and confectionery, holidaymakers on the beach and provincial youth at leisure-133; With smiles and gestures Chilikov stretches them all into poses that any sensible and right-thinking person would find hard to achieve. Here the artistic coercion the photographer exerts on his own models turns out to be their pleasure as they liberate the instincts slumbering behind feigned, model behaviour. Behind all the variations in uniform something common to all mankind is revealed, previously unseen and always unpredictable, coming as a shock and revelation to the unprepared viewer. It would seem such demonstrative behavior exaggerated and understood in Post-Soviet (self-) liberating society (when in fact Chilikov adopted this style) should have already gone out of fashion of its own accord and no longer please or interest us - but this is not the case. Amid the simplicity of European direct photography (the objective style of recording reality as seen in the Dusseldorf School and catalogues of professions a la August Sander has become mainstream today), Chilikov's photographs are both amusing and compelling: because here the peacockery of the models is directed at the voyeurism of viewers, and the unmasking of nature turns out to be the unmasking of society, and consequently, of the public. The show must go on, in society too.